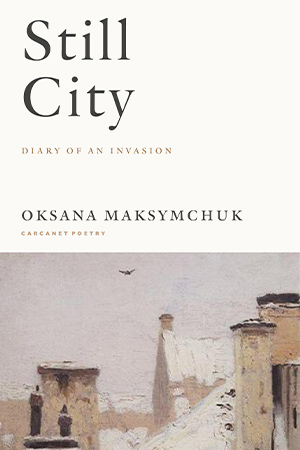

Still City by Oksana Maksymchuk

Manchester, UK. Carcanet Press. 2024. 122 pages.

Manchester, UK. Carcanet Press. 2024. 122 pages.

In Oksana Maksymchuk’s Still City, war and everyday life collide, causing a dramatic shift in perspective about what matters and what one carries—physically and emotionally. The poems in this collection form the diary of an invasion that shifted the course of global politics and priorities. Intimate in its awareness and honesty, this collection threads together social media posts, news items, eyewitness accounts, and official documents as a dedicated speaker carries readers through the anticipation of—and acceptance of—catastrophe.

Similar in tone and subject matter to Serhiy Zhadan’s “Take Only What Is Important,” “Emergency Bag”—one of the collection’s initial and most jarring poems—challenges readers to reconsider priorities and materialistic necessities. The line “Pack all you need to survive” opens the poem and segues into a variety of possible locations: “in the wild, in the snow, in the cellar.” The localities to which the speaker refers imply two significant aspects of the Ukrainian refugee experience: entering uncertain circumstances and the unknown as they navigated new countries and new languages. The phrase “in the cellar” conjures recollections of the many news stories depicting brave Ukrainians who survived for weeks and months with little food or water in cellars in order to escape occupation. Facilitating the sense of escape into uncertainty and into the unknown are carefully placed em dashes in the third stanza: “When a city / resounds with sirens or falls — / suddenly — silent.” The em dashes—combined with the lines’ reliance on the words “falls,” “suddenly,” and “silent”—help create sonic dissonance but also a sense of being suspended in time.

“War Shy” addresses the harsh reality with which Ukrainians have lived since 2014 but that the rest of the world seemed to have forgotten until 2022: Ukraine has been at war with Russia since Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea and other eastern Ukrainian regions. In four concise stanzas, war life and everyday life blur as a speaker recalls “a country bled / for a decade” and how “Friends of friends have died / on the frontline.” Meanwhile, references to “warm dessert / homemade pie, custard / with a real vanilla bean” balance the acknowledgment that Ukrainians “mourn” those who have died. The speaker describes the war as “secreted and remote” and as a “presence” that one can “sense” with one’s “gut and spine.” These descriptions capture how, since 2014, the war has become an inescapable presence for Ukrainians, despite the brief, even happy, interludes from the violence.

“Post-Truth” addresses another harsh reality: the influence of Russian propaganda in prominent political spheres across the globe, which Ukrainians and their allies have worked tirelessly to combat. The poem boldly confronts propaganda that denied events like Russia’s bombing of hospitals and schools and the mass graves at Bucha: “Some say it didn’t happen / Others that it was staged.” The speaker uses words like “exhibition” and “arrangement” to reinforce how many people believed that the war in Ukraine was a staged event. The speaker also acknowledges the dehumanization Ukrainians experienced by those who doubted the war’s severity: “It looks bad but isn’t / Sounds bad, but they’re lying.” Interestingly, the poem does not incorporate any punctuation at the ends of lines until the final one:

In any case, how do you know

you didn’t dream it all up

some terrible night

drinking and vomiting

until blackout?

The question mark is a powerful end punctuation in this case. It reiterates the skepticism with which many in the public and many in politics viewed the war. The word “blackout” possesses a formidable duality, implying a state of unconsciousness as well as the literal, mandated state of blackout the Ukrainian government imposed in order to protect citizens.

“Algorithmic Meltdown” leaps headlong into the influence social media has on the general public as well as how social media became a platform of witness during the war’s early days. The speaker confesses that they “too prefer / funny puppy videos / flowers and minerals, food porn” rather than images of “blackened privates exposed.” Other violent images, such as a “liver / smeared over asphalt,” form the poem. Anchoring it, however, is the heart-wrenching fifth stanza:

Somebody’s daughter

sandwiched between the slabs

of concrete.

The stanza’s placement mirrors the word “sandwiched.” The word’s placement within the stanza creates a sense of being crushed, and linguistically “sandwiched” echoes “slabs.” The linguistic minimalism of the phrase “of concrete” attempts to alleviate the image’s figurative and emotional pressure, but such minimalism places emphasis on the brutal image instead.

Unlike many pieces of literature that emerged during the war’s initial days, Still City is timeless. Its terrifying images are immediate, and its observations about human nature and human behavior during grave times is eye-opening and startling. In it, realism and restraint combine to form an unforgettable, and necessary, contribution to the literary canon.

Nicole Yurcaba

Southern New Hampshire University