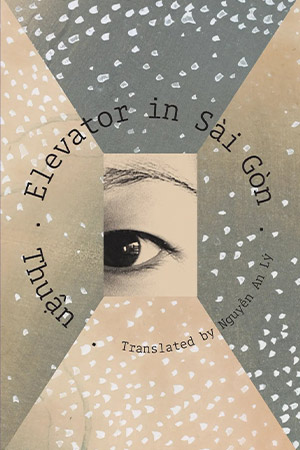

Elevator in Sài Gòn by Thuận

New York. New Directions. 2024. 194 pages.

New York. New Directions. 2024. 194 pages.

After winning the 2023 National Translation Award in Prose for the English translation of Chinatown, Nguyễn An Lý returns with a translation of Thuận’s 2013 Elevator in Sài Gòn from the original Vietnamese. Of note, the geographical range the author and translator bridge, with Thuận in Paris and Nguyễn An Lý in Ho Chi Minh City, reiterate the primary dual setting of Elevator in Sài Gòn.

What initiates the action of this satire is the death of the unnamed narrator’s unnamed mother from falling down an elevator shaft in the lavish Sài Gòn home of her son, Mai. When the daughter returns to Sài Gòn for the funeral, she discovers a photo, which her mother had hidden, of a Frenchman with the name of Paul Polotsky and a Parisian address written on the back. The narrator embarks on an obsessive search for that man through the streets of Paris and into fifty years of Vietnamese history from 1954, marking the Geneva Accords that divided Vietnam, to 2004, when the mother dies. The inquiry into the link between the photo and the mother’s death, which animates this pastiche of popular genres from the detective novel to the sitcom, is merely the frame for what I would describe as a philosophical text.

With satire, Thuận diagnoses the failure of the revolution, accompanied by layers of questions regarding our ability to really know anyone. Based on this, I argue that Thuận is not solely interested in critiquing the failure of socialism but also in portraying the amnesia produced by the pursuit of wealth in hypermediated environments that hollow out life.

She shows that social roles dominate, and this is evident in the early days of the revolution and in 2004. The narrator critiques the way her parents “fulfilled the role of the New Socialist Persons” when their desire to distance themselves from the aberrations in each spouse’s history leads to divorce. Fast-forwarding to 2004, her brother, Mai, is celebrated universally for his wealth in the same country where his parents had to sell everything they owned for his mother to secure a fellowship to study in France in 1977. Thuận is at her satirical best with her portrayal of the performance of filial nationalism at the mother’s funeral, rivaling Hollywood films in production and aesthetic value, used by her brother to sell more overpriced real estate. This chapter is suggestively followed by a description of her mother’s admiration for the performance of Kim Il Sung’s funeral.

Through deft translation, the narrator is presented as a wry, yet not unsympathetic, observer of human foibles. It is remarkable that the satire comes through so clearly in translation. Certain phrases heighten the effect, my favorite of which is “beastillionaire.” Though I don’t know how much that is, the phrase aptly conveys the potentially horrific machinations required to become super wealthy. Precise idiomatic American word choices, such as “couch potato,” are to be applauded, but one phrase, presumably translated directly from Vietnamese, stands out for its descriptive power. The evocative “loose bike chain” serves as a metaphor for the betrayal of trust that the socialist state mistakenly bestows upon those who go rogue.

Though I remain engaged in the questions Thuận uses this text to examine, I would not call this a satisfying read, but that is partly the point. In fact, her identification of a clear preference for convenient fictions about ourselves and others may be her greatest achievement. It is to be expected, then, that the narrator finds out the truth about Paul Polotsky but doesn’t understand her mother any better as a result.

The problem I have is one that plagues satire in general: Elevator in Sài Gòn lacks an emotional core. Though exceptionally difficult to create a compelling narrative in such a philosophically ambitious novel that aims to pinpoint the sources of our contemporary malaise, moments of distracting confusion alienate the reader in a way that does not seem intended. Ultimately, however, this reinforces the novel’s conclusion. We may all be in this together, but we are stuck with perceiving ourselves and others through the roles we perform and the expectations they entail.

Janet Graham

University of Nebraska at Kearney