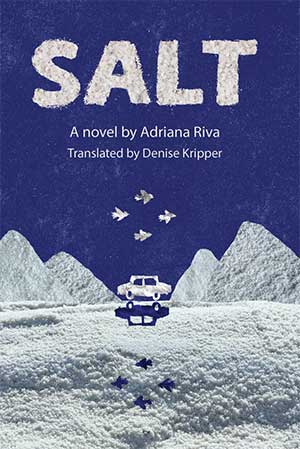

Salt by Adriana Riva

Houston. Veliz. 2024. 146 pages.

Houston. Veliz. 2024. 146 pages.

Late in Adriana Riva’s stirring debut novel, Ema, our narrator, arrives in her mother’s erstwhile hometown in provincial Argentina, where workers will soon raze a warehouse containing items amassed over many years by current and former residents. Nobody will really miss the old building, but its demolition—and eventual replacement by a fitness complex—attests to time’s remorseless forward march. In a novel explicitly concerned with intergenerational miscommunication, a less polished writer might’ve said more about the warehouse, belaboring its status as a temporal symbol. But Riva, an Argentine poet and literary magazine editor, makes but brief mention of the building’s imminent destruction, leaving it to us to make the thematic connection. This, plainly, is a novelist capable of tremendous subtlety, and one who has palpable respect for her readers’ smarts.

Salt owes its title to the ground on which Riva’s characters walk. Joined by her mother, Elena, and two other family members, Ema drives from Buenos Aires to the Pampas in central Argentina, where salty earth has made a few people quite rich. The trek—undertaken to retrieve a box, marked with the family’s name, found in the warehouse—might’ve been a warm-hearted journey, but that’s quickly ruled out by the reemergence of tension between Ema and Elena. Ema, we learn, broke her back as a child, falling from the roof of the family’s house. Though both women recognize that Elena, a self-confessed inattentive parent, probably could’ve prevented the accident, they’ve never had a proper discussion about it. That’s about to change.

Modest in scope, Riva’s novel is not out to dazzle with the intricacy of its prose. Occasionally, her commitment to concision leads to graceless metaphors, as when Ema tells us that her relationship with Lucas, her partner, “has turned into an abandoned campsite I can never make up my mind about leaving.” (These intermittent lapses can’t be blamed on Denise Kripper, whose translation is without obvious flaw.) Far more often, however, this is a book that derives immense power from plainspoken language. During an argument with Elena, Ema regrets that she’s resorted to a childish dig: “It drives me crazy that I can’t insult her as the grown woman I am.” Though they were never close—an old photo shows them posing at arm’s length, “like a family of bowling pins”—it’s nonetheless painful for Ema to see her mother, “finite and terribly human,” take ridiculous measures to fend off aging.

This concise novel has an epic’s worth of insightful things to say about parenthood and the stubborn patterns of behavior that shape every family.

Kevin Canfield

New York