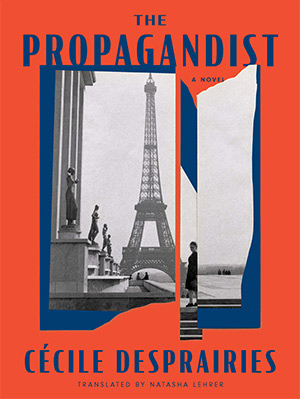

The Propagandist by Cécile Desprairies

New York. New Vessel Press. 2024. 199 pages.

New York. New Vessel Press. 2024. 199 pages.

First published in France in 2023 and immediately nominated for the Goncourt, The Propagandist is a fist-in-your-face cautionary tale. A thinly veiled fictional autobiography, it covers the genesis, blossoming, demise, and aftermath of one of France’s most painful episodes: namely, French collaboration during World War II. This first novel is a second career for Germanist and historian Cécile Desprairies who has penned six books about France under German occupation and its aftermath.

The Propagandist’s two female protagonists are Lucie, an ardent Nazi sympathizer and one of the main propaganda architects in Vichy France, and her daughter. The traditional mother-daughter act takes a dark turn when the daughter-narrator discovers her family’s moral crimes against French Jews. As the wartime patronage system of family and friends is “whitewashed” and sealed into a postwar oath of silence, the games of glamour and glory resume with obliviousness.

The male characters provide a study in contrasts. They are Lucie’s first and second husband, both collaborationists. One is a fanatical scientist, the scion of a wealthy and influential family of Alsatian industrialists; the other an haut fonctionnaire issued from a long lineage of Burgundian landowners. The scientist meets a mysterious, untimely death during the liberation of Paris; the high-ranking civil servant lives. Lucie raises her children from her second husband as if they were her first husband’s. Her sole release is the “gynaeceum,” her ritual daily meetings with female relatives who reminisce, recriminate, cry, laugh, and gossip in her living room.

The narrator’s passage into full cognitive dissonance from this delusional world is fostered by two antiheroes: her retiring grandfather, a former POW, and a young female Jewish acquaintance who commits suicide. In due time, her reassessment of reality sets the record straight. Just as she listened to Lucie’s stories in the huis-clos of a car as a child, the narrator years later puts her to rest between her first and second husbands. Lucie’s car was the ubiquitous “deux chevaux” mass-produced in factories initially owned by André Citroën, a Jew. Her grave is the family burial ground of the second husband. Such ironies abound in the legacy of collaboration.

Desprairies’s language is laced with Faulknerian violence. She skips from minute observations to real-life language laced with colloquialisms, colorful epithets, and cultural references. Natasha Lehrer’s translation fluidifies the narrative by reorchestrating sentences and paragraphs and eliminating tautological phrases. This, however, somewhat dulls the flavor of the text and abridges the author’s turns of thought, especially when French cultural references are scrambled into images more suitable for an English ear. Overall, the smooth translation does justice to a Greek drama of emotional entrapment and release.

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin