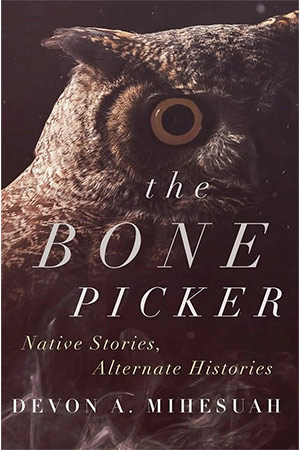

The Bone Picker: Native Stories, Alternate Histories by Devon A. Mihesuah

Norman. University of Oklahoma Press. 2024. 174 pages.

Norman. University of Oklahoma Press. 2024. 174 pages.

In this anthology, noted Choctaw scholar Devon A. Mihesuah offers a dozen tales combining people from history and legend as well as supernatural beings from tribal lore. The book’s title comes from a traditional job in Choctaw society: Hattak fullih nipi foni (man who picks flesh from bone, or “bone picker”) who cleans bones as a part of care for the dead. Mihesuah details a character’s encounter with a bone picker at work: “On top of the scaffold lay a dead person. Straddling that unfortunate soul was the bone picker. I held my breath as I watched him pull flesh from the bones and drop the red and brown pieces into the fire.” This once-common Choctaw funeral practice is so foreign to most people that it has a macabre feel. This “otherness” will be the key strength for most readers, in turn horrifying, scaring, or puzzling.

Mihesuah is a meticulous scholar. Her nonfiction works are detailed and well written. Unfortunately, some readers find her style does not always work in fiction. To them, the prose can be awkward, with unnecessary detail. The Bone Picker’s short-story format alleviates this. So, readers disappointed by Mihesuah’s novels may be pleasantly surprised. Those who loved her novels will be pleased by the return of some of their favorite characters. Fans of Mihesuah’s nonfiction will find several of the historical figures and events she has previously covered here in a fictional format.

These stories of rural southeastern Oklahoma introduce a wide variety of colorful Choctaw characters. Though lightly sketched, they are believable and relatable. But the real stars of the stories are the other-than-human creatures. Since many of the stories are suspenseful, I will avoid spoilers by focusing mainly on the creatures. The Shampe is the only being familiar to most readers. These “huge, furry, lumbering beasts, had followed the Choctaws over the removal trail from the Southeast to Indian Territory” and are better known as Bigfoot. The story also discusses the Choctaw “lighthorse” police that are detailed in two of Mihesuah’s nonfiction works.

The Kowi Anukasha (forest dweller) is the Choctaw version of “little people” like the leprechauns of Irish lore. But the Kowi Anukasha are unique. Though mischievous like leprechauns, they are also the teachers of Choctaw medicine people. The scariest creature is a shadow figure known as the Nalusa Chito (large black being). Like most Choctaw supernatural beings, the Nalusa Chito doesn’t harm well-intentioned humans. But a terrible fate awaits those who have evil thoughts. The Kashehotapolo (old woman scream) may seem familiar because of “deer woman” in stories of other tribes. Unlike these, the Choctaw Kashehotapolo is a half-man, half-deer creature of the deep forest who is indifferent to the fate of humans scared by his earsplitting scream.

My favorite story in The Bone Picker is “The Cornfield.” This atmospheric tale concerns the only evil being in Choctaw mythology, the Opa (owl) that shapeshifts to get away with murder. My second favorite, “Tenure,” betrays my bias as an academic. It is about a “pretendian” who tries to benefit from posing as a Native American. Mihesuah makes the character a professor, allowing her to bring great insight to the story. Though other’s tastes will vary, the diversity of stories in The Bone Picker ensures readers will find something they like.

Lee Hester

Norman, Oklahoma