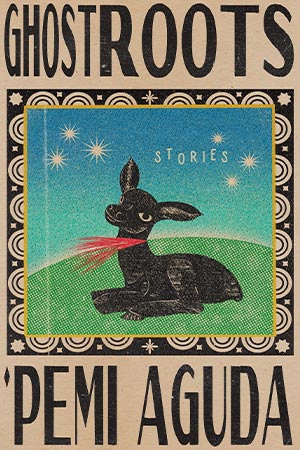

Ghostroots: Stories by Pemi Aguda

New York. W. W. Norton. 2024. 272 pages.

New York. W. W. Norton. 2024. 272 pages.

Ghostroots engages parallel worlds where one universe collapses into the other. The reader wanders the in-between, the liminal space where reality is questioned and the portal between the physical and the spiritual is torn. Pemi Aguda bases her literary horror in the ordinary, the domestic, and the everyday. The author presents the reality of the average Lagosian who, in their bid to survive, must navigate paranormal realities.

Strategic pressure in the right places can shatter the soundest of minds. But isn’t that what society should be, insane? At least with this revelation the problem will not be diagnosis but honing coping mechanisms that allow the shattered mind to thrive. Ghostroots abandons the façade of functional society to expose the underbelly of the pig masquerading as a sloth. The uncanny is reality in all twelve stories, and the movement across both worlds makes distinction unnecessary.

The opening story, “Manifest,” sets the book’s tone. Three generations of women are trapped by their resemblance and collective memory. The narrator metamorphosizes into her mother’s worst nightmare, Agnes, a woman so unhinged she cuts her daughter’s “arms with a razor, stuffing the wound with powdered chili pepper, locking her out of the house if she played in the street too long” and reemerges as her granddaughter to continue the torment. This reincarnation of Agnes through the narrator disrupts the status quo by courting its hostage with their innate needs and desires. Repressed needs become physical pain that breaks through the surface as boils/large pimples. The narrator surrenders to the surge of desires coursing through her and completely emerges as Agnes, her alter ego.

“What is a house?” In “Hollow,” this repeated question untethered a sentient house, the main character in the woman’s life. It makes sure she has safety, is sensitive to abuse, and kills any perpetrator that makes it hostile ground for the inhibitors. A simple story of the ordinary is heightened because someone looked beneath the hidden cupboard and uncovered a colony of rodents festering. These rodents are not villains; they are part of the ecosystem. One must wonder if their exposure to sunlight disrupts established patterns and purpose. In Aguda’s stories, karma always catches up with men who commit violence against women, whether they are the three men in “Things Boys Do” or the male characters in “Hollow.”

In “Alhaji Williams Street,” when the youngest boy in every family on this long street dies without any apparent illness or ailment, despite desperate attempts to keep them alive, there is a haunting and inevitable resignation that leads to an eerie ending. The stories also explore grief, wanting, and longing, misplaced affection, and the ability of the human condition to shatter a person and flatten them to shadow. It explores the different ways people explode under pressure and how those decisions have a domino effect. The paranormal and mundane tango in a dance whose next steps you cannot foresee because the beauty is not just in the intricacy but in the rhythm and seamless fluidity.

The world in Ghostroots is flexible, so language stretches to reflect the collapse of default realities. Language is specific and not used in the self-aggrandizing smush of rhetoric-jarring words that mean nothing. Everything is possible in a way that collapses the fourth wall and submerges the reader into the hollow.

The Western literary tradition, with America and Britain at its center, finds new and creative ways to other literature outside its hubris. The arrogance of being at the center of literature means that everything coming from the margins is surreal, magical, or speculative, all subtle ways to undermine the richness of the human experience on the African continent and beyond. “Speculative” is a term often used when describing Aguda’s work, but is it speculative when it is grounded in the reality of everyday life? Speculative implies speculation and conjecture, which is a disservice to the multitude of realities presented in the text.

The stories interrogate tropes and bring them to the forefront of consciousness. The book reads each person differently. Any good work of art criticizes what a reader brings to the text. No reader is a blank canvas—they enter the text with expectations, millennia of experiences, and preconceived notions. This book nudges the reader to explore the history they bring to the text and how their worldview interacts with the characters and situations in Ghostroots.

Delight Ejiaka

University of Nevada, Las Vegas