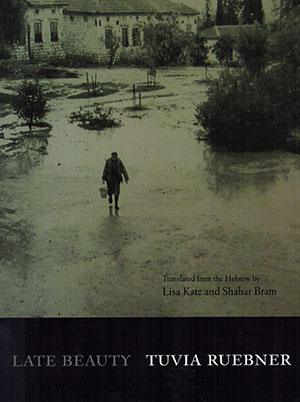

Late Beauty by Tuvia Ruebner

Brookline, Massachusetts. Zephyr Press. 2017. 103 pages.

Brookline, Massachusetts. Zephyr Press. 2017. 103 pages.

Late Beauty exemplifies that, while he is fluent in both German and Hebrew, Tuvia Ruebner’s first language is indeed poetry. This collection of poems displays his Innigkeit (interior depth), which firmly affixes him to the German tradition of Israeli poetry, as opposed to the Anglo-Saxon/British one. As he acutely focuses on the interiority of his individualized self, Ruebner poeticizes a philosophical exploration on subjectivity, beauty and aesthetics, death and memory, and the unique relationship between place and dislocation that is so central to an immigrant’s worldview. Such diversity in subject matter engenders Ruebner’s polyphonic textures.

The collection is organized associatively rather than chronologically so as to formally simulate memory’s nonlinearity. Ruebner’s resistance against chronological organization is a resistance against the West’s linear notions of time. His ekphrastic poems enliven works of art that populate walls of such collections as Jerusalem’s Israel Museum and London’s National Gallery; his postcard series animates past experiences of and reflections on places like Hebron, Zurich, Jerusalem, and Šaštín; and the poems that focus on personal history revivify those Ruebner has lost, either due to the Holocaust or other unhistorical tragedies, such as his son’s disappearance in South America, and tether them to his consciousness and therefore to ours.

Ruebner’s memories are vivid moments that make up the gallery of his consciousness, so that just as he visits Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, Marc Chagall’s The Fall of Icarus, and the Zen paintings in museums, he revisits his little sister who is “forever thirteen years old,” his Freemason father who planned on becoming a poultry farmer somewhere like Moshav Shavei Zion, and his lost son, all of whom haunt his poetry. Ruebner’s exploration of the inner workings of memory dissolves the veil between life and death, which is blurred in his consciousness: “Life is death and death is also life.”

The reader is left with the unwavering conclusion that Ruebner’s homeland is poetry, wherein “language is nothing but mourning for lost tenderness.”

Sasha Strelitz

University of Denver