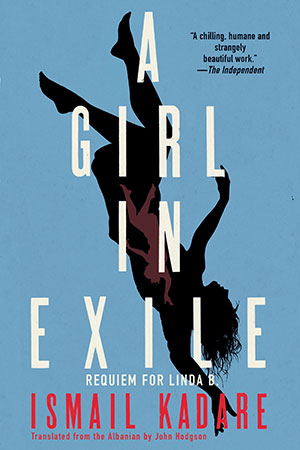

A Girl in Exile: Requiem for Linda B by Ismail Kadare

Berkeley, California. Counterpoint. 2018. 192 pages.

Berkeley, California. Counterpoint. 2018. 192 pages.

Ismail Kadare is one of the most lauded writers-in-translation in the English language, certainly one of Europe’s most important writers, and virtually the singular representative of Albanian culture to the anglophone world. Kadare’s career as a literary opponent of totalitarianism, which he once declared the natural enemy of the writer, has rendered him among world literature’s most important voices. He is also a master ironist.

A Girl in Exile, his latest novel translated into English, from the original Albanian published in 2009, is one of Kadare’s cruelest exercises in irony. It is a painful, sometimes comic mystery dedicated to unraveling why Linda B.—a girl on the cusp of womanhood living in forced internal exile with her once-royalist family in the rural reaches of Albania during the twilight of Enver Hoxha’s dictatorship—commits suicide. The novel is by turns a probing exploration of the strict censures on everyday life—from which coffee shop one drinks at to the friends and lovers one has and the art one makes—under a totalitarian regime, and by turns epic in its connections among the present of life under Hoxha in the 1980s and the ancient past of Western mythology and history. Kadare interweaves Orpheus, Caligula, Skanderbeg, the early Hoxhist years, and communist Albania’s dissolution, morphing the political topology of Albania into the personal present of the novel’s protagonist.

The great irony is that the story of Linda is not hers but instead is told from the perspective of the tortured male artist type, the playwright Rudian Stefa, whom Linda fixated on as the ideation of all that the cultured world of Tirana, beyond her reach in exile, offered. They never met, though he touched her life briefly through a signed book (“For Linda B.”) that his lover and Linda’s friend, Migena, gifted Linda. A Girl in Exile—with its opening dedication “to the young Albanian women who were born, grew up and spent their youth in internal exile”—is a novel about Rudian, about his responses to Linda’s suicide, his efforts to solve the “enigma” of why she did it, and his growing obsession with whether he was the cause.

In taking readers through the steps of solving the enigma, which ultimately leaves Rudian untouched and, after the fall of communism, an even more successful playwright for the experience of this crucible, Kadare decenters the particular traumas of womanhood under dictatorial rule. Instead, the author favors a “human” story of “truth” revealed through art—through the meaning and nonmeaning, as Rudian muses, of attempts to crystallize experiences of state violence in language—to map the ethical relations and responsibilities people have to one another even as they are oppressed by dictators. There is irony, too, in Rudian’s presentation as a self-prescribed genius intellectual dissident who is nonetheless favored by the party because he stands to expose those more dangerous than himself. (Hoxha, who appears at the end of the novel in a gambit of quirky surrealism, takes particular interest in Rudian.)

This undercutting of the tale of the genius artist, of the tragic Lermontovian hero revivified after communism, hardly makes up for the novel’s failures to relate the pain and experiences of Linda or Migena except through Rudian. But the narrative focus on Rudian exposes the role men too often assume in telling women’s stories—under Hoxha, after Hoxha. A Girl in Exile achieves what so few of these wearisome novels about sad-urban-male-artist types today do: it makes clear, through their very lack of interest in other humans as anything but artistic muses, the ease with which artists—under communism or capitalism, repressed by tyranny or freed from it by revolution—dehumanize and make myths of the pain of others.

Sean Guynes-Vishniac

Michigan State University