Furari and Venice by Jiro Taniguchi

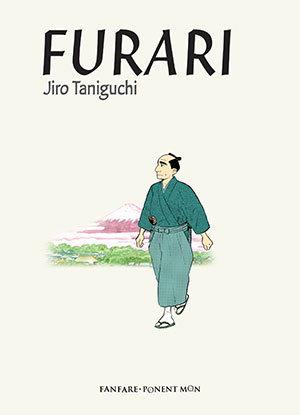

Furari. Doddington, United Kingdom. Fanfare / Ponent Mon. 2017. 208 pages.

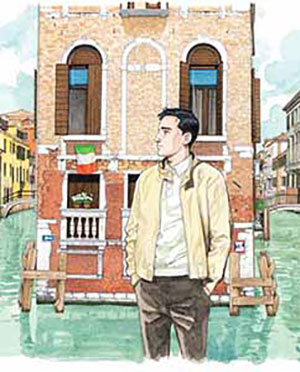

Venice. Doddington, United Kingdom. Fanfare / Ponent Mon. 2017. 120 pages.

The world of comics lost a great artist when Jiro Taniguchi (1947–2017) died last year. He was a rare talent with unique vision, able to summon up beautiful worlds of quiet reflection. Thankfully, Taniguchi was prolific. He left behind a trove of works that are slowly making their way to English via Fanfare/Ponent Mon. Their latest offering is two comics, the 2011 black-and-white Furari and the 2014 painted Venice, which was commissioned by fashion company Louis Vuitton.

Furari’s plot is hardly enticing. In a time before accurate measuring devices, a man hopes to calculate the distance of one degree along a meridian. To achieve his purpose, he walks the same path every try, training himself to keep an accurate step as a human measuring wheel. Page after page he walks his course, counting his steps. Not exactly a recipe for high drama. But this is Jiro Taniguchi.

Anyone who has read his 1992 comic The Walking Man knows Taniguchi can easily make a captivating work of art about a person taking a walk. Furari has that same feel. His lead character, the surveyor, wanders through a bustling town, full of life and the goings-on of ordinary people. His footsteps carry him through the works of artist Utagawa Hiroshige and the poet Kobayashi Issa. The world around him is of ukiyo-e and haiku. The surveyor’s mission is a scientific one, but his heart is full of beauty, and his mind goes on flights of fancy. He flies on the wings of a hawk and dives down into the river depths with turtles and otters. The man’s wife is supportive of her husband’s obsession; the two go on pastoral dates among cherry blossoms and drift on lake boats, sipping sake and generally being in love. Somehow, it is perfect.

Furari’s translator, Kumar Sivasubramanian, did an excellent job of balancing the dialogue and poetry of this comic. Poems are rarely easy to translate, but Sivasubramanian makes it seem natural and effortless. There are a few notes to catch you up, but most of it stays on the page, allowing you to get swept up in the work.

Furari uses the fine line and lush detail typical of Taniguchi’s comic work. His characters remind me of Katsuhiro Otomo’s—“realistic” but with expressive mouths and features. Terry Moore is another artist who matches Taniguchi’s ability to draw fully realized human beings that make use of the plasticity of the medium. The world the characters of Furari inhabit, however, is pure Hiroshige. Furari is a love letter to the brilliant Edo period artist, using his sense of perspective and design liberally.

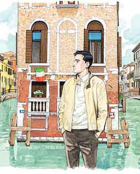

In stark contrast to this is Venice, which is fully painted in a style that begins as loose watercolor but slowly tightens up as the story progresses. Venice was commissioned as a travel book in a series from Louis Vuitton, meant to showcase the beauty of this famous city. Taniguchi strings together a base narrative of a man who finds a box of painted postcards in a suitcase left behind by his dead mother. Being a character in a Taniguchi comic, he, of course, goes on a walking tour, seeking out some of the locations and mysteries of his mother’s previous life.

Venice has very little text but manages to tell an engrossing story. Taniguchi’s art swings from grand, full-page landscapes to a simple white page with a bowl of soup (possibly my favorite). I’ve never been to Venice, but after reading this I sure want to go. And that, I suppose, is exactly the point!

These are two beautiful works from Taniguchi that I am happy to add to my library. And I am keeping spots open for the rest of his comics that will hopefully become available. Just keep walking.

Zack Davisson

Seattle, Washington