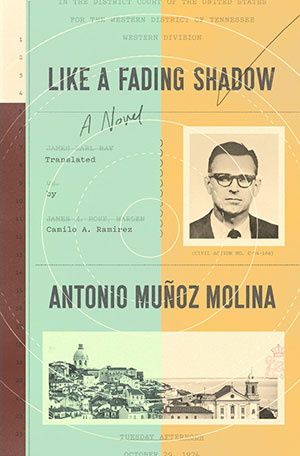

Like a Fading Shadow by Antonio Muñoz Molina

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2017. 312 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2017. 312 pages.

Celebrated Spanish novelist Antonio Muñoz Molina’s new novel, Like a Fading Shadow, is a detailed work with multiple narrative threads woven together with the author’s reflections on the nature of literature. It is at once the story of James Earl Ray’s short, miserable stay in Lisbon while fleeing law enforcement and an account of the writerly obsession that would motivate one to dramatize the life of an infamous murderer.

Lisbon is presented both as dark and desperate through Ray’s perspective and as the vibrant city that inspired, almost counseled, Muñoz Molina as a young thirtysomething writer. We are told the story of a criminal, a young Muñoz Molina activating his literary imagination, and the “present-day” Muñoz Molina—an accomplished man of letters who studies Ray, reflects on his own youth, cherishes his wife, and contemplates the relationship between life and literature.

This writer—older, wiser, and filled with esteem and curiosity for the “unpremeditated” beauties of life—gives the novel purpose, a mission. Occasionally, we are presented with axioms: “A novel is a state of mind. . . . Literature is the desire to dwell inside the mind of another person.” But the mode of Muñoz Molina’s inquiry is primarily exemplary. In precise detail, he recounts the life, crimes, and capture of Ray with dispassionate prose. As he accounts for every minute of Ray’s time in Lisbon, the reader feels anxious, hunted as Ray must have. As he delineates Ray’s past and approaches the fatal, climactic moment of Dr. King’s assassination, the reader’s moral outrage is backgrounded by a fascination with Ray’s each step and a feeling of rushing toward the inevitable. And this, I think, is the experiment of Like a Fading Shadow, the example of Muñoz Molina’s beliefs about literature.

While the Lisbon of the author’s youth is a joy to read, an invigorating experience we are thankful to see through his eyes, James Earl Ray’s Lisbon is a fearful place—we feel his anxiety, are averse to it and want relief, though we ought to want him captured. Against our better selves, the reader sympathizes with Ray’s disintegrating nerves and psyche, if only because we ourselves experience them as well through their description. In this way, Muñoz Molina not only asserts that a novel is a state of mind; he makes his point by exploring the role of perspective in literature. By contrasting his experience of Lisbon against Ray’s, and embellishing the thoughts of his youth with the reflections of his present age, Molina invites us to witness the workings of literature—of life understood by the novel.

Carson Schatzman

University of Oklahoma