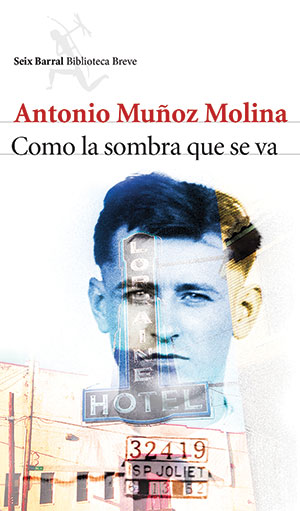

Como la sombra que se va by Antonio Muñoz Molina

Barcelona. Seix Barral. 2014. ISBN 9788432224157

In his ambitious new book, the Spanish writer Antonio Muñoz Molina recounts two brief visits to Lisbon. One was his own, in the 1980s, researching the novel that would make a name for him, Winter in Lisbon. The other was that of James Earl Ray, twenty years earlier, on the run having killed Martin Luther King Jr.

In his ambitious new book, the Spanish writer Antonio Muñoz Molina recounts two brief visits to Lisbon. One was his own, in the 1980s, researching the novel that would make a name for him, Winter in Lisbon. The other was that of James Earl Ray, twenty years earlier, on the run having killed Martin Luther King Jr.

In 1967 Ray broke out of a Missouri jail. In April the following year, he took a room with a view of the hotel that Dr. King used in Memphis. He bought a hunting rifle, binoculars, and soft-tip cartridges. When King went out onto the balcony, Ray fired once. The bullet pierced the civil rights campaigner’s jaw and smashed his vertebrae. He never recovered consciousness.

Ray fled to Canada, then to Lisbon. There he spent ten days trying and failing to obtain a visa or passage to Angola before returning to London. He was collared when a Heathrow official spotted his assumed name, Raymond Sneyd, on a Canadian wanted list. Ray confessed, avoiding a jury trial and with it possible execution, but soon recanted. He continued this disavowal until his death, in jail, in 1998.

Lisbon is where the story comes to life for Muñoz Molina. The King assassination offers the author a chance to explore one of the most shocking events of the twentieth century alongside his own career, combining a true-crime tale with a literary memoir that attempts to explain his obsession with this murder, and with Ray himself.

The novel thus mixes two almost incompatible genres. One is a taut true-crime tale. The other is a memoir about a bohemian author leaving his long-suffering wife for a pretty young journalist. The link between the two is the need to create fiction. Ray constantly reinvents himself, while Muñoz Molina invents others. The murderer combines an inflated sense of self-worth with moments of paralyzing doubt and self-recrimination. The young novelist feels the latter about his writing.

Ray never tired of telling his version, or versions, of events. For the novelist, conspiracy theories respond to the mind’s need for coherent stories. Muñoz Molina underplays some political aspects of the murder, such as Ray’s active support for segregationist politicians of the day, or the state’s failure to protect King, despite heavy surveillance. Instead, we read his own domestic reminiscences, which do less to explain the crime than they demonstrate his own fascination with it.

Benjamin Bollig

St Catherine’s College

University of Oxford