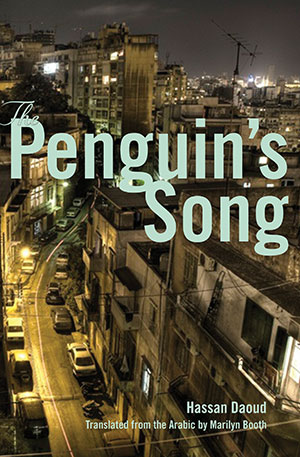

The Penguin’s Song by Hassan Daoud

Marilyn Booth, tr. San Francisco. City Lights Books. 2014. ISBN 9780872866232

Hassan Daoud, a prominent Lebanese short-story writer and novelist, was born in 1950 in southern Lebanon and moved as a child to Beirut. First published there in Arabic (Ghina᾽ al-Batriq) in 1998, The Penguin’s Song, one of his eight novels, is an account of the Lebanese civil war, or rather of its devastating mental effects on those who were physically unharmed by it.

Hassan Daoud, a prominent Lebanese short-story writer and novelist, was born in 1950 in southern Lebanon and moved as a child to Beirut. First published there in Arabic (Ghina᾽ al-Batriq) in 1998, The Penguin’s Song, one of his eight novels, is an account of the Lebanese civil war, or rather of its devastating mental effects on those who were physically unharmed by it.

“The Penguin” himself, a deformed young man, has fled with his parents from the war-torn city to an apartment overlooking Beirut. The father, removed from the little shop he had, and hence from meaningful work that enables him to support his family and from sane contact with acquaintances outside that family, slowly declines. His sight begins to fail and he eventually dies. The mother cooks daily meals, carefully preserving leftovers, takes walks, and visits neighbors in the apartment building. Both worry about their son, who narrates the story. Utterly isolated by the consequences of war and his disability, he weirdly records and responds to the minutiae of life in the apartment, attempts to read, and watches with morbid intensity an adolescent girl living in the apartment below. It is he whose observations chiefly create Daoud’s careful analysis of the psychological state consequent to displacement, a state of baffled meaninglessness, of hope apparently infinitely deferred, of unhealthy obsessions divorced from reality.

The pinched, thwarted, and enclosed lives led by the family—a form of suspended animation as a “temporary” resettlement is drearily extended as far ahead as its members can see—result in hypersensitive overreadings of behavior in the son, who suspects that he is the subject of gossip in the apartment building. His fantasies about the girl—he imagines her wandering naked around her apartment, and attaining puberty—are an index of his sexual and other frustrations. On one occasion, as the Penguin leaves the building to return some writing to an editor, he “knows” that his father will remain positioned in a certain place until he estimates that his son has reached the building’s entryway; and that the girl will not be able to see his satchel, which he carries in a particular way; and that her mother, “though no doubt she is aware of [his] departure,” will not be able to see it either.

Daoud’s plangent novel sensitively dissects the states of exile and deracination.

M. D. Allen

University of Wisconsin, Fox Valley