Written on the Body

Beginning with the Voyager space launch and moving through explorations of touch, Hungarian writer Zsolt Láng examines his relationships to music, books, and art.

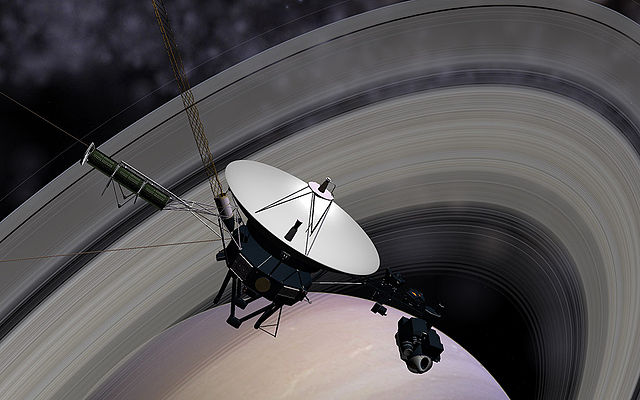

When the two Voyager space probes were launched in 1977, I was 170cm tall and weighed 68 kg. I was not planning to write books; in fact I never even scribbled in the margins of books. Having passed the successful entrance exam and nine months of compulsory military service, I was preparing for my first year at university. I was solving math problems as a pastime and wearing an A-shirt and cotton Y-fronts all the time, although underwear was a rarity then, just like pork.

By now space probes have traveled farther than twelve times Earth’s distance from Pluto—their speed 20,000km/h (within two seconds they would complete an orbit of the Earth)—I am fifty-one years old, 171cm tall, and 74kg in weight, I scribble all over my books and wear no underwear, although after the fall of the Communist regime the shops are nearly choked with lingerie brands of every conceivable denomination. One of the spacecrafts is headed toward the Centaurus constellation, the other toward Orion, and, if all goes well, in forty-five thousand years they may reach “inhabited planetary systems with intelligent life-forms.” For this eventuality they carry a message. The “letter” made of sounds and images of the Earth is engraved on a gold-plated copper disc 30cm in diameter; all in all there are 115 photos, 21 kinds of voices from the Earth, and 27 musical recordings on it, as well as greetings in 54 languages. The Hungarian-language greeting goes as follows: “We send greetings in the Hungarian language to all peace-loving beings at Universe” (in a sentence that happens to be patently wrong; if it were correct, there should be something called “Outer University”).

In my childhood I threw several sealed-up bottles into the Szamos with my name, address, and a short but carefully crafted letter inside. I kept waiting full of excitement and apprehension. I imagined the lonely wanderer floundering up and down on the river’s waves between unknown banks. I imagined myself in its place: the mere thought gave me goose bumps. I even experienced the solemn moment of the bottle’s opening but had my misgivings if that moment was indeed solemn. How will the unknown reader respond to my letter? What will he think of me? I was already looking at myself with foreign eyes: as if it was I whom they extracted from the dripping bottle and inspected to see if I was worth anything. I had to face the possibility that I would not please the bottle’s opener and that, disgusted, he would throw me back into the water.

In Montaigne’s three-volume Essais, published between 1580 and 1588, there is only one piece dedicated to friendship. But the way he writes about the beloved friend, Étienne de la Boétie, allows us to surmise that all the pieces in the collection were written under the inspiration of this friendship. This is corroborated by the Latin pensée in the study among whose book-covered walls these works were written, dedicated to the most beloved, closest and dearest, the best, most accomplished, wisest and most perfect friend, the likes of whom could not be met in their century, to his never-ending remembrance. In Montaigne’s essay, friendship is a dialogue: to get lost, to lose oneself in the other, not to hold onto anything that is only one’s own or only of the other, but to share. Die-hard Montaigne scholars consider this statement completely foreign from the oeuvre and would be all too happy to uncover that it originates not in Montaigne himself, while another group of researchers would assign the same importance in the glaring light surrounding the oeuvre’s summits, to gestures of self-effacement, of relinquishing the “self,” as they would to intentions of delineating that “I.”

In the midst of the loudest triumphal march of the Nazis (this being still before Stalingrad) angels writhe on the cobblestones, their wings trampled underfoot by gangs of men swarming out of the pubs, who shake their fists at the sky as a sign of victory, and yet, and yet it is revealed that the tortuous convulsions of the defeated are more human than the drunken apogee.

When I heard for the first time Furtwängler’s 1942 recording of the Ninth, I was glad there was no one else in the room. I felt the dialogue between him and Beethoven uncommonly intimate. No, he wasn’t even speaking with the work—or he was, of course, but in the meantime he spoke out, out of their conversation even. In the midst of the loudest triumphal march of the Nazis (this being still before Stalingrad) angels writhe on the cobblestones, their wings trampled underfoot by gangs of men swarming out of the pubs, who shake their fists at the sky as a sign of victory, and yet, and yet it is revealed that the tortuous convulsions of the defeated are more human than the drunken apogee.

Later I listened to the recordings of others, of Knapperstbusch from Berlin, or Bruno Walter with the New York Philharmonic: their renderings didn’t speak about such matters. As though it were an answer or solution (it is not, of course), I realized on an umpteenth listening that what was going on in the background was in fact a dialogue between two persons, Furtwängler and the percussionist, Werner Thärichen, who plays a key role, almost overcoming his bodily limits, playing in a manner that is nearly inhuman. As though he had shed the plaster off the cockaded edifice of the Ninth, baring it to the bone so that the inner structure could shine through. Is this a shining? Hardly. A dramatic, self-baring nakedness, rather, that flees from the onlooker’s gaze in panic.

* * *

The dialogue conducted with the book first occurred to me when I felt the embossed letters on the cover. I woke up in the small hours looking for something to read in the heap of books by my bed, and my fingertips came across the letters in relief. JEANETTE WINTERSON. The novel in the book speaks about love, about “the story written on bodies.” On the cover there is a naked woman against a background of green hibiscus leaves. The camera’s lens focuses on her back; her body is slightly out of focus. But the hibiscus leaves are just as sharp, as if the photographer focused on the close relationship between the reddish-brown profusion of hair and the deep green of the leaves. The paperback volume’s leaves, made of 120 gram tree-free paper, are pleasant to the touch.

From that moment I was in an ongoing dialogue with the body of the book, continuously confronting the story it encloses with the stories written on my own body. I borrowed the book from somebody with whom, that is to say, with whose story I was also engaged in a dialogue: I knew that for years this person had been tormented in a love triangle and, though willing to escape, felt unable to break away.

The books written on parchment also send a thrill down one’s spine because even if we forgot for a while what they are made of, our skin would nevertheless sense beneath the kindred material’s cold cuticle the warmth and throbbing of times past.

When letters were still engraved on clay tablets, reading must have been a lot more sensuous and more cautious at the same time. The books written on parchment also send a thrill down one’s spine because even if we forgot for a while what they are made of, our skin would nevertheless sense beneath the kindred material’s cold cuticle the warmth and throbbing of times past. Is leafing through a book an erotic act? It is erotic in Bourdieu’s view, but in the sense given by Adam Green, where the focus is on reciprocity, it is not—because who could tell what the book feels. But in both Bourdieu’s and Green’s terminology, the book is a means of “accumulating erotic capital.”

I am incapable of reading books that emit an odor of sweat, or whose touch reminds me of a cold and sticky palm. On the other hand, I love reading books that smell of shoe polish. Or on whose margins their previous reader had made a list of the choice words. It must make quite a difference if a book is read from left to right, from right to left, or in columns from top to bottom. I read a book differently if I bought it from a bookshop or if I borrowed it from a library. Differently, if the librarian is a young girl or, on the contrary, if she reminds me most of the folktales’ abject old hag.

Once at a Kolozsvár party I asked the host, the son of a well-known philosopher, how would it affect the result of my research if I approached the wine bottle on the table with the tools of physics or with those of chemistry. Without letting me finish the question he lambasted me, saying that the bottle had to be approached from the direction of the bottle. The others nearly started applauding at this maxim (I have since repeatedly experienced that fatuousness and vacuity have the greatest success as a rule) but at the time I only nodded, deflated, put in my place. Only later did it occur to me what, were I to approach from the direction of the bottle, could save me from relying on the received methods. Can there exist a direction from the inside inward? I was left completely alone in the large company, and, while I joined the majority with a broad grin on my mug, I felt a pang of metaphysical solitude engulfing me, together with the bottle.

Not long ago I had an intense correspondence, what I may call friendly, with somebody. We met every once in a while, had long talks, and drank fine wines. I believed I had found true friendship, the likes of which this century hasn’t seen. And then one night my friend’s entire correspondence appeared on my computer screen. At first I couldn’t even grasp what happened. It was due to a fatal coincidence, broadband interference, the likelihood of which is one to a billion. I read the letters written to others, and what I found there nearly made me faint: “spineless,” “selfish,” and “empty-headed” were some of the terms my friend had used to characterize me, but I was even more taken aback by the fact that his most intimate confession that he had shared with me had also been sent to at least three other pen-friends. From his fatally shared mailbox, the exact opposite of what I had known about him emerged—in fact not its opposite, but its variant fashioned of an entirely different material. The one with whom I had corresponded and to whom I had entrusted my secrets was no longer—that is, I was no longer.

Even through this sad story of mine, I am engaged in dialogue with the book. When I reach the point where the protagonist leaves his/her beloved after learning about her terminal illness, in vain does s/he justify this choice with the fact that the beloved woman’s husband is a physician and, by his side, she has a better chance of being cured or of lengthening her life; in vain the unfathomable qualms of the break-up, I can only see this and what follows through the thorns of desertion.

At its launch eighteen years ago, the novel’s author alluded to real-life persons and destinies. From these allusions I put together for myself a well-rounded story: about the author, aged thirty, and the editor, aged fifty, who leaves her husband to live with the author, but in the end her illness makes her return (in reality the husband is no physician but an acclaimed British writer). In this well-rounded story, I identified the book’s narrator with the author. If I met her, the author, I would take up the thread from where the book leaves off. I would reciprocate her self-baring; I would share with her my stories kept secret, assimilating them to what I have read. She would of course listen to me in embarrassment, an embarrassment growing more and more acute at the sight of my gaze, of my color rising, at the sound of my voice nearly strangled with huskiness, now racing on, now slowing down, at my almost sensuous, hot panting. For I would be a complete stranger. I couldn’t touch her because she would continuously withdraw, like a snail into its house. She would smile on, would politely thank me for reading her book. And she would definitely not manifest this by snapping something rude and scathing at me.

* * *

I can take refuge in the book. I need not suffer anyone’s callousness or strangeness. I need not be put off by the weird timbre of their voice, hair-dye color, clumsily plucked eyebrows. What if they like garlic and I don’t? Sooner or later this would inevitably lead to conflict. What if they should want me to travel to the countryside, while I am a dyed-in-the-wool metropolitan? What if they are appalled by my habit of going around without underwear? In the book I can hide my gaze. (For a long time I didn’t understand why my other favorite, Karajan, always conducted with his eyes closed. Obviously this was his way of always allowing close the one with whom he was conversing. If I switched off the light now, the night birds in the nearby groves would fly over the ring road to settle on the pear tree’s branches.) The book protects me from reality and prepares me for it at the same time: that one day I should nevertheless touch somebody, open them, and read through their pages. Read the letters that were incised into their bodies, like reading Braille.

If I were a woman, before I started conversing with a man I would give myself over to him, so that later, while we are talking, he need not close his eyes. I would give myself over to him as simply, unmediatedly, and self-evidently as objects offer themselves up to the gaze in Jean Baudrillard’s essay “Photographies”: “If something wants to be photographed, that is precisely because it does not want to yield up its meaning; it does not want to be reflected upon. It wants to be seized directly, violated on the spot, illuminated in its detail. If something wants to become an image, this is not so as to last, but in order to disappear more effectively. And the photographing subject is a good medium only if s/he joins in the game, exorcizes his/her own gaze and judgement, revels in his/her own absence.”

The borrowed book leads me on stunning paths. I learn many things about its owner, about the owner’s way of leafing through books. If that leafing hand is light or heavy. I find a thread of hair: s/he uses chamomile shampoo. With a bit of imagination I will see even more of them: I feel what passages held their gaze longer and follow the working of their brain, I can see how the neurons are connected, forming electric circuits that are read by an invisible phase-detector, to find out from the flickering of impulses what they intend to communicate. I can see their nerve cells in front of my eyes, exhausted, looking for nutriment, drinking up the fresh enzymes that arrive through the capillaries, like a flock of sheep at the watering place. And interestingly, while I put all my thirty-nine questions to this person conjured up in front of me, in the articulation of the answer I learn a few oddities about myself (for example, that I like striped socks and stories about hackers).

When love is about to reach its fulfillment, the storyline in the book comes to a standstill. The lethal illness reveals the body. It peels off its stories together with the skin and voices the ultimate question: Will everything be buried with death?

Even if I hide to read in a snug little nook, the conversation between the book and me will inevitably be public. Like some judge, I keep weighing it. Is it not too reader-friendly? Written with too fast fingers? A superficial would-be novel? But suddenly something happens. When love is about to reach its fulfillment, the storyline in the book comes to a standstill. The lethal illness reveals the body. It peels off its stories together with the skin and voices the ultimate question: Will everything be buried with death?

Of course, when two bodies embrace, what touches the other is merely the cuticle of dead cells. How does the life breathing beneath break through the dead surface? By emitting signals. By the fact that all cells join in the feverish exchange of signals. None is left out. A touch is a touch if I depend on it, if it embeds me somewhere, if I would miss it, yes, if it has me in its yoke. When do I get there? When I start hearing the other. (In German, “dependence” is Hörigkeit, which Heidegger in Being and Time connects to the verb hören, “to hear”—I depend on it because I hear it, we could say.) Across the skin’s dead layer, the whispering beneath the skin hears the whispering beneath the other’s skin and answers it. The coming-into-being of touch depends on hearing the other.

Hans Knapperstbusch’s Ninth is inflated; Bruno Walter’s Ninth is clichéd. Furtwängler’s is full of drama. Drama is generated not by dialogue but by the way conflict becomes present in it. For me, something becomes present if it touches me. How can one play Ode to Joy in April 1942, on Hitler’s birthday? This is a dramatic question, but if it were only that, my curiosity feeding into my question would generate at most an indirect involvement, of the literary type. I listen to Furtwängler hypnotized. After all, it is his shattering answer that touches me, his singular, doubting, tragic performance, the gesture with which he turns his back on the rabble. Or, more precisely, he shows that they are a rabble, who will thereafter not even require to be named by the gesture of turning one’s back on them. It is Furtwängler’s profoundly personal, radiant solitude that touches me. Heidegger, for whom solitude was such an all-important medium, what is more, a philosophical term, did not turn his back on this rabble but, on the contrary, in 1933, when he was elected rector, gave a speech in the forest of Nazi flags and arms raised to sieg-heil, about the forsakenness of man in the midst of existence. He discoursed on the being-self of Dasein, carried around on the shoulders of Jew-beating students. Still, his tragic answer can also touch me. I conjure up the image of a jittery Heidegger in the SA squads’ braced shorts, giving orders to his disciples educated on Being and Time.

* * *

Let us buy a pair of cats, Huxley advises his young friend who has made up his mind to write novels, psychological novels at that. For humans live behind heavy curtains, but cats can be observed unmediatedly. Cats are naked, says Huxley; on the contrary, we humans cannot see through curtains, and what is more, those curtains are adorned with all manner of mythological overlay, adding further layers. I have no intention of writing psychological novels, yet a few years ago a cat moved in and has stuck to us ever since. Unwittingly I keep observing its behavior. What irritates me most is that it touches everything. Not only that, it rubs itself against everything, as if this were its only way of existing in the world. As a result of my observations, I can safely affirm that a cat never photographs objects: it uses other methods. It goes to them and rubs all veils off of them, down to the bone, peels off their bark, the romantic, illusory, or rigid phantasmagoria, the delusions of melancholy daydreaming, the appearance-novels.

Reading sharpens my hearing, makes my skin more sensitive, brings out desires that have long hibernated in the mud, but is never up to touch. What is touch?

I keep my palm among the book’s pages all night, yet it would be downright ludicrous if I started speaking about the mystery of touch. I can even employ the most efficient methods of accumulating erotic capital, I can get immersed in the research of the objectification of erotic currency, but without being touched, the whole thing is worth exactly as much as a penniless broker’s attempt to orchestrate a bear raid without short selling. Reading sharpens my hearing, makes my skin more sensitive, brings out desires that have long hibernated in the mud, but is never up to touch. What is touch?

In my childhood, I didn’t have the possibility of watching films not recommended for viewers under eighteen years of age. And even if I somehow managed to, I didn’t learn much from them. As soon as they started kissing, there was a cut to the morning, the man was already putting on his tie, the woman inserting her graceful, slim feet into her shoes. But something important had happened: before, they had addressed each other formally, but now they were on first-name terms. This shift was there to signal that everything had happened.

In one of the world’s most famous paintings, the creator, reaching out from his cloak, touches Adam with his index finger. Behind him are the Lady of Wisdom, a host of angels and demons, spirits of good and evil, and in the mural’s corners the grave-looking Sibyls, messengers of possibilities. As if all were fusing into his touch. Still, I see the image the other way around. I see this touch peeling the whole gang off God and Adam, ridding them of the hosts and legions of the world of appearances. Touch strips naked. What happens afterward is another question, but there, in that moment, in the world’s most famous touch, even God is naked. He knocks the plaster off himself, as the percussionist does with the Ninth.

Touch strips naked. What happens afterward is another question, but there, in that moment, in the world’s most famous touch, even God is naked.

There is nothing more boring than a world without touch. The cat jumps on the windowsill. It immediately “steps in”: with the hectic up-and-down jerks of its head, fast stamping of feet, and wriggling of its tail, it is negotiating the optimal body position for the jump. Then, seeing that the fourth-floor window remains closed and it has no chance of breaking through the glass, it gives up its position. With unfeigned boredom it yawns at the glass sheet.

Reading is the cat’s stamping about in front of the window. Reading continuously tries to ascertain whether A equals A. But A can only equal A if it does not equal it, for if I draw the equality sign, then there must be two A’s. However, if the existence of two A’s is possible, then what is equal can at most be isomorphic. The dialogue in which the participants are continuously ascending or descending, forever stepping out of their previous positions, is in fact aiming at its own termination. It aims at ending the apart-ness of equals. Dialogue is a headlong dive into the river: the place I splash in exists only at the moment of the touch, neither before nor afterward.

In a less well-known painting, Jesus withdraws from the fingers of Mary Magdalene. Noli me tangere, touch me not, he says. The best painting of the theme probably belongs to Titian. Touch me not, for I am not yet ascended to my Father, Jesus says according to the gospels. Why does he say that, since a few hours later he would explicitly ask Doubting Thomas to thrust his index finger into the hole opened in his side by the soldier’s spear? Why can’t Mary Magdalene touch him?

For the answer, let us look at another painting. In Caravaggio’s Raising of Lazarus, the two women, Mary and Martha, sisters of Lazarus, lean above their brother; they almost throw themselves on him to cover him with kisses and enfold him in their embraces, but as though a magic cocoon were shielding his body, they do not touch him. A touch of Jesus is enough: it is enough to make whole the woman with an issue of blood, to restore the sight to the blind, to clean the lepers and make the lame walk. But the dead Lazarus (or Jairus’s daughter) is raised by Jesus without touching them. Lazarus, like the risen Jesus or Adam resurrected to life, is not touched with an earthly touch. Real touch is “tactless”; it scorns our “touchiness.” When, having reached the novel’s end, I close its back cover, I stare at it almost incredulously: what is that book doing by my bedside? I see it as faded, almost seedy, a sloughed-off snake’s skin.

The two Voyager space probes will soon cross the boundary of the solar system. No one knows what awaits them. Their apparatus will go dead; they will no longer be able to transmit signals of their whereabouts. They will merge into outer space. They will be dead until they encounter a beam of light to penetrate inside them.

Translation from the Hungarian

By Erika Mihálycsa