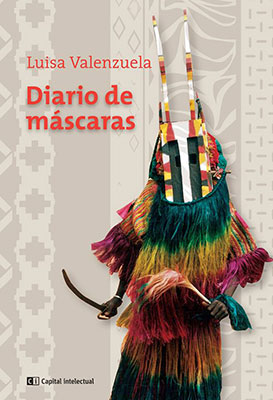

Diario de máscaras by Luisa Valenzuela

Buenos Aires. Capital Intelectual. 2014. ISBN 9789876144612

Masks, among other things, may be monstrous or cute ambassadors of distant secrets, peoples, and truths. By cataloging her masks, passionately accumulated while traveling, Diario de máscaras enables us to trace the random outlines of what writing, traveling, and living have in common for Luisa Valenzuela: the intense need to avoid the plan, to get lost. Valenzuela’s new travelogue brings with it the undeniable fascination of distant peoples and places—from the equatorial jungle to the Dogon in Mali, Amazonia, Papua New Guinea, China, India, Japan, Nepal, Tibet, Egypt, and the Argentinean Chaco Salteño—as “narrated” by her masks. Valenzuela confesses: “Every one of my masks is for me like a book. They tell me many stories.” She also suggests that masks show rather than hide and that traveling and getting lost imply, for her, a need to write.

Masks, among other things, may be monstrous or cute ambassadors of distant secrets, peoples, and truths. By cataloging her masks, passionately accumulated while traveling, Diario de máscaras enables us to trace the random outlines of what writing, traveling, and living have in common for Luisa Valenzuela: the intense need to avoid the plan, to get lost. Valenzuela’s new travelogue brings with it the undeniable fascination of distant peoples and places—from the equatorial jungle to the Dogon in Mali, Amazonia, Papua New Guinea, China, India, Japan, Nepal, Tibet, Egypt, and the Argentinean Chaco Salteño—as “narrated” by her masks. Valenzuela confesses: “Every one of my masks is for me like a book. They tell me many stories.” She also suggests that masks show rather than hide and that traveling and getting lost imply, for her, a need to write.

Writing, for Valenzuela, is not different than traveling because she believes in “writing with the body, putting every one of the cells in movement to create, which is in itself a discovery process,” and her approach to both is similar in its lack of structure, where the technique is getting lost, probably because “the big surprises emerge from the unexpected. There is nothing like getting lost to better find ourselves.” This technique brings us closer to the places and peoples of her stories, letting us, if only for a minute, inhabit their masks.

In Diario de máscaras, Valenzuela adopts the anthropologist’s role, which she had “lent” to Marcela Osorio, the main character of her novel La travesía (2001; see WLT, Spring 2002, 238), to produce a diary rather than a complete and organized description of places and cultures, with the purpose of “showing the scraps of her trips.” As in her novels—in which, she explained in a 2001 newspaper interview with María Moreno, “I don’t have structure. I never assemble a novel knowing where it is taking me. They tend to be exploration texts”—her diary feels like a set of exploratory texts and suggestions about places. While one could say that the irony of Valenzuela’s new book is that she commits the sins she warns against—to provide a guide, to suggest a route—the call to get lost and the value system she outlines redeem her from such sins.

Diario de máscaras packs the same positions that characterize Valenzuela’s work—her engagement with social causes, feminism, and sustainability—in the form of a travelogue that stops to reflect on the responsibility of travelers: to avoid stealing the meaning of places, peoples, and masks; the cultural role of women as creators of the masks and therefore of deeper meaning; and the need for travelers to behave like true anthropologists and to try not to contaminate the setting with their presence. Diario is a guide of sorts to situations and an art of traveling that invites readers to go on their own trips to places and among peoples and therefore into a deeper understanding of themselves.

Carolina Sitya-Nin

University of Oklahoma