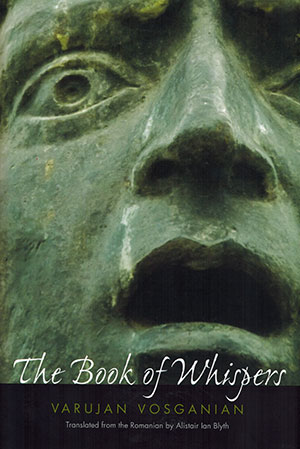

The Book of Whispers by Varujan Vosganian

New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2017. 346 pages.

New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2017. 346 pages.

Far too little is written about or by the Armenian peoples. Granted, the Republic of Armenia is a small country (population: 3 million), sitting adjacent to Turkey, whose Ottoman Empire started the infamous Armenian genocides in 1915. The genocide involved the Ottomans’ systematic extermination of 1.5 million Armenians between 1915 and 1919 (this history not yet a reconciled matter between the two countries).

The Book of Whispers, though very much Armenian in subject, is equally set in the author’s environs in southern Romania. Author Vosganian describes himself as a Romanian-Armenian whose ancestors escaped Anatolia (Turkey) in 1915 and settled in Romania. Armenians have played a large role in the cultural history of Romania; the book is nearly as much about Romania as Armenia and is written in Vosganian’s native Romanian tongue.

This poignant work is a great homage to those Armenians who either did not survive the genocides or lost family and home, and how they coped (or did not cope, in most circumstances). The central character in this factually sound story is Garabet, Vosganian’s grandfather, whose suffering and storytelling eventually form much of the author’s own psyche. As a youngster, Vosganian was believed to be a “child old in years” and “destined to be the family historian.”

The book reads as a novel narrated both in the first and third person, but sometimes the author breaks form and speaks directly to his reader—a startling effect, to be sure. As a paean to his fellow Armenians who suffered such persecution and slaughter, the story is loaded with a myriad of names of the deceased (all of the characters in this book are real).

At times, The Book of Whispers can be a confusing read. Not penned in chronological order, the author swings from one era in history to the next, sometimes on the same page. “For me, the storyteller,” he admits, it is quite “hard to keep to the thread of the story.” Be sure and read esteemed Romanian translator Alistair Blyth’s introduction, a good primer for what is to follow. Readers familiar with Armenian, Romanian, and Turkish history will find this work immensely engrossing; those who are not may well be a bit lost.

Vosganian’s ethereal prose is at its best when describing wartime atrocities. It becomes a detached voice—a hypnotic voice—when grisly details are not spared. The sheer brutality of it all produces a kind of numbness in the reader. Then again, perhaps detachment is the only way to endure such terror. The face on the book’s cover depicts a person suffering unspeakable torment. Consider it preparation for what follows within its pages.

Virginia Parobek

Lancaster, Ohio