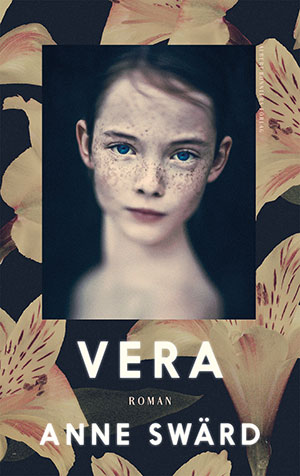

Vera by Anne Swärd

Stockholm. Albert Bonniers. 2017. 344 pages.

Stockholm. Albert Bonniers. 2017. 344 pages.

Vera is a strange book: the darkly glittering wrapping of high romance conceals a bitter core, a compound of the collaborator’s secret shame and guilt, and the hypnotic effect of power. Sandrine, the storyteller, knows that she might have been a postwar femme tondue—a “horizontal collaborator”—paraded in front of jeering crowds with her head shaved and a swastika painted on her forehead.

When she arrives in Sweden in 1945, Sandrine is only seventeen, a blond and lovely waif, mysteriously healthy looking compared with the other refugees—but pregnant. Eventually, we learn that she had lived in occupied Poland, and a German officer (Sascha) chose her to be his live-in companion while his men set about eliminating local Jews and partisans, including Sandrine’s family. Sascha slept with his trophy, fed her, showed her off, and trusted her. Knowing that she was damned anyway, Sandrine stayed trustworthy until the German collapse, when she walked out and, through luck and courage, snuck on board a refugee transport.

She is soon picked up by a Swedish man: Ivan, a gay aristocrat who decides to marry her as a cover for his illegal sexual exploits. Sandrine now has to deal with Ivan’s mother, brothers, and sisters-in-law, all of them tall, handsome, full of obscure intents, and bizarrely cruel. The wedding day is a gothic nightmare on an ice-bound island where the bride’s wild dancing with a wicked relative ends in childbirth, screams, and bloodied sheets.

Once more, Sandrine is the victim of a ruthless imposition of power and endures luxurious, miserable incarceration with a survivor’s passivity. Maternal love is out of the question; her little Vera (from verus, truth) watches her with Sascha’s cold blue eyes. Finally, a family servant engineers an escape for the child’s sake, and Sandrine and Vera go to ground in a house by the sea. There, after many cliff-hangers, Sandrine and one of Ivan’s old lovers offer each other the precarious comfort of love.

Vera is a daring experiment by Anne Swärd, who has previously touched on big subjects but in “ordinary” settings. This ornate, high-toned morality tale flirts dangerously with melodrama but achieves real stature thanks to the accomplished, poetic language circling the trip-wire topics of oppression and submission.

Anna Paterson

House of Glack, UK