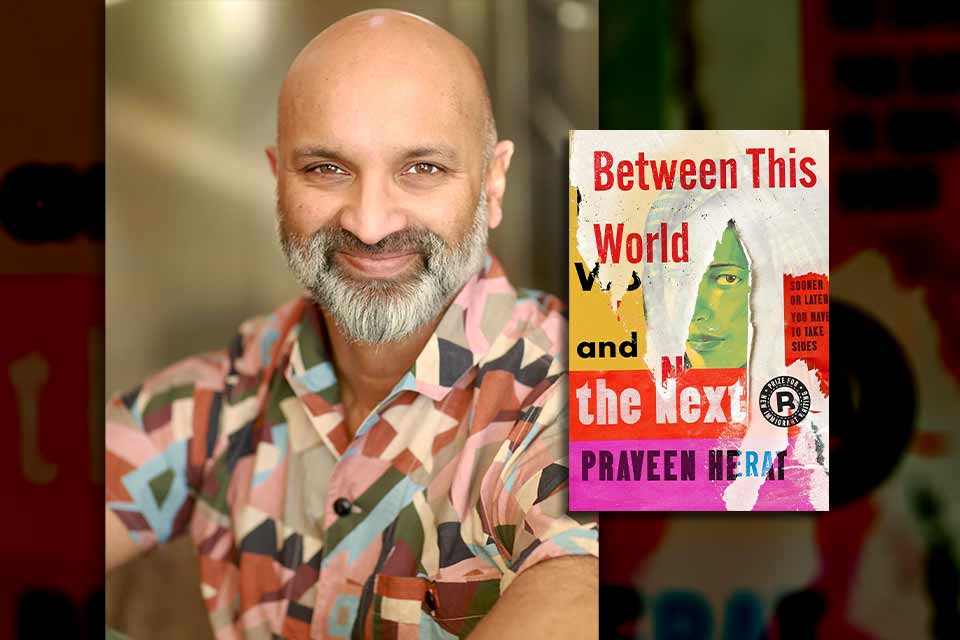

7 Questions for Praveen Herat

In Praveen Herat’s debut novel, Between This World and the Next (Restless Books, 2024), a British war photographer uncovers crime and corruption in a Cambodia beyond the rule of law. Sitting on the sidelines becomes impossible in this novel that won the 2022 Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing.

Q

Between This World and the Next is a literary thriller. What makes a good thriller, and what are some of your favorites?

A

Defining “literary” and “thriller” is quite a challenge without value judgments! I think some people would argue that thrillers emphasize action and that their writing is primarily focused on driving a plot. Others would say this is antithetical to “literary” writing, in which the lines we confront—around moral questions, for instance—are blurred and the reader is compelled to pause and reflect rather than rattle along under a narrative’s momentum.

But I’m not these people! When I tackled my degrees in English literature, plot was something you hardly ever talked about. The exception was studying Shakespeare—I loved poring over the volumes of Geoffrey Bullough’s Narrative and Dramatic Sources in the library. These gather all the original tales that Shakespeare drew on—and ultimately “remixed”—to create his plots. Examining what he borrowed, what he changed, and trying to understand why, had a massive influence on my writing mind.

A truly effective thriller—and I find much of Shakespeare thrilling—carries the reader on a journey of emotion and also compels them to intellectually confront certain ideas at a specific moment in time. A master of this art can bring peaks of emotion and intellect together—or pull them apart—as and when required. I guess that’s what I’m constantly striving for.

Q

Could you tell us about your time in Cambodia and how it inspired you to write this novel?

A

On my first morning in Cambodia in 2004, I pulled back the curtain of my hotel room window to see two men haggling over the contents of a car’s trunk: a gun that I immediately recognized as an AK-47. Whether in the hands of a Tamil Tiger in my country of origin, or strapped to the chests of separatists in the Second Chechen War, was there a more ubiquitous object in the news, then or now? How had this weapon proliferated in every corner of the globe?

As a writer, I felt that this was my territory because, above all, I’m interested in what is everywhere but rarely spoken about. The simplified explanation—that the fall of communism had spawned an international illicit trade in military stockpiles—sparked a broader fascination about the evolution of the post-Soviet global order, including the phenomenon of oligarchs who had risen from obscurity to limitless power: an arc that underpins not only Between This World and the Next but the sequels I hope to have the opportunity to write. (In fact, Between This World and the Next is just the beginning of a planned tetralogy, and I’m desperately hoping that people will read it so I can write the next, and the next, and take readers on a journey right up to our present moment and beyond.)

Many stories from Cambodia’s dark history also influenced the book. The mysterious assassination of Fearless’s father in Cambodia, for instance, draws on the murder of the British academic Malcolm Caldwell in 1978.

Q

When you were in Cambodia, what did you notice people reading? What is literary life like there?

A

When I arrived in Cambodia, I was struck by absences. There were very few people over sixty: a whole generation had been wiped out, including its artists, intellectuals, and writers. Most of the country’s books and paintings had been systematically destroyed. So, while you would see textbooks under schoolkids’ arms or people reading newspapers, it was rare to see people reading books in public.

At the same time, Cambodia’s extraordinary aesthetic achievements were everywhere, most obviously in architecture: from the temple complexes of Angkor to the modernist masterpieces of Vann Molyvann, both of which appear in Between This World and the Next. This juxtaposition between genius and emptiness, between ornate intricacy and barrenness, was dizzying. Despite this, I was always aware of the Khmer people’s capacity for resilience and reinvention, not least in the way they reused and repurposed everyday objects: a spirit that I still find deeply inspiring.

Q

What research did you do for the novel?

A

A decade’s worth—a lifetime, really—much of which is evoked in the book’s acknowledgments. The works of Svetlana Alexievich, Susan Sontag, Anna Politkovskaya, David E. Hoffman, Douglas Farah, and Andrew Feinstein, to name but a few, were particularly important. So was a treasury of photojournalism, which was absolutely essential for a novel with a photojournalist as a key protagonist.

But I think you can read Between This World and the Next and not be obliged to linger on the scaffolding behind it or even the big political and ethical questions that drive it. Nevertheless, I hope there are readers who recognize and appreciate that ambition, for whom it becomes a spur to dig deeper into the challenges it confronts relating to pacifism and nonviolence, the decline of the nation-state and the rise of stateless actors, our responsibility to intervene in conflict, the effects of power and powerlessness, and the tug between selfishness and altruism within each of us.

Q

Though born in England, you now live in Paris. Where in Paris do you return for inspiration?

A

My life in the city doesn’t have much to do with the picture-postcard view of Paris. I love watching the world go by on Saturday mornings on Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Denis, which is a gritty and sometimes heartbreaking mix of privilege and poverty. I love being in the Rino Della Negra at Stade Bauer on Friday nights to watch my beloved Red Star FC take to the pitch. I even love sitting on a packed RER to the banlieues, which remind me of my childhood in the South London suburbs. I guess it’s variety, then—diversity, difference, rubbing together—that keeps me alive, whether in Paris or in any of the cities I’ve been lucky to live in.

Q

What trends in culture have recently captured your attention?

A

There’s something that recoils inside me when I hear the phrase “cultural trends.” More often than not, it seems to be in the context of marketing: how can we tap into a zeitgeist and monetize it?

The trend in culture that captures my attention is an antitrend that sets out to evade being captured by our attention. I’m thinking of a number of writers and thinkers who are exploring what it means to step away from the attention economy. Most important has been Michael Sacasas’s Substack “The Convivial Society.” I’d also recommend Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing. The ideas they address are much on my mind because my second novel, nearing completion—which is very different from Between This World and the Next—is focused on how we connect with others and what constitutes truly meaningful connection and community.

Q

What are you most excited about reading at the moment?

A

I’m always most excited about filling gaps in my literary knowledge. At the moment that means reading Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; I just don’t know how it’s always passed me by. And Proust has been on my bedside table for a while. This autumn, I hope to celebrate being granted French citizenship (one in the eye for the Rassemblement National) and finish up Du côté de chez Swann—or die trying!

Praveen Herat was born in London to Sri Lankan parents and educated at Oxford and the University of East Anglia. He lived in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, for several years, a period that marked him profoundly and prompted his research for what would become Between This World and the Next. Since 2010, he has lived in Paris.