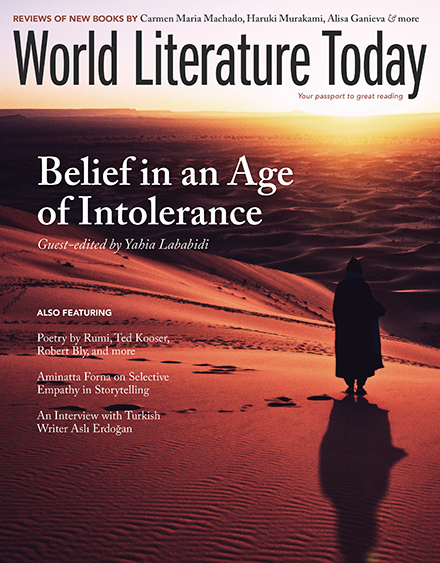

Writing as Judgment or Scream: A Conversation with Aslı Erdoğan

After finishing a master’s degree in physics and writing her thesis on the Higgs-Boson particle, Turkish writer Aslı Erdoğan (b. 1967, Istanbul) worked for two years at CERN as a particle physicist then moved to Rio de Janeiro. After the publication of her first novel, The Shell Man (1994), she quit her scientific career and devoted herself to writing. Her third book, The City in Crimson Cloak (2001), brought her international recognition. With this novel, often described as a modern classic, Erdoğan was chosen as one of “Fifty Writers of the Future” by the French magazine Lire. Back in Turkey, Erdoğan began working as a columnist for oppositional newspapers, and after the failed coup attempt of July 2016 she was arrested on the pretext that she had been a literary adviser to a pro-Kurdish newspaper. Erdoğan was released after a worldwide human rights campaign, but her trial still continues. In July 2017 the French government awarded her the Légion d’Honneur, but her travel request to receive it was only recently approved. After an initial phone conversation, we met on Heybeliada (Princes’ Islands), near Istanbul, to continue our exchange.

Erkut Tokman: You’ve said that your books, starting from your first novel, The Shell Man, are in the form of novels and short stories but are difficult to place in certain genre categories with set boundaries. You’ve also mentioned that you see yourself as an autobiographical writer. How do you account for these preferences?

Aslı Erdoğan: I am not a “novelist” in the traditional sense of the word, nor even a storyteller. The most important element of my literature is language itself. I use a narrative style that is based on images and metaphors, very intense and penetrating (a critic calls it a “crossfire of metaphors”), as close to poetry, even music, as possible. The words reflect, invoke, and echo each other; obscure shadows gather in their corners, silence is filled with meaning as much as words are, while darkness and void are as signifying as light. . . .

More and more, I forego the main conventions of the art of storytelling as dramatization, personification, and identification. In my latest book, The Stone Building and Other Places, the narrators are not typical characters whose stories or even personalities have specified boundaries; they appear and disappear more like members of a tragic chorus and take turns stepping into their conjoined story. Or they are rather like empty shells in which different voices pass through, sometimes a scream, a roaring laughter, a tune . . .

When asked years ago, “Do you write about yourself in your books?”, I faced the fundamental puzzle of my own writing half-jokingly: “Yes, whenever I find her!” A self is not found but created, invented, built and rebuilt. I set out by saying, “I am my narrated self,” and for many years I have been hopelessly circling between what is said and what remains unsaid, between what is already lost and what is yet to be born, only changing orbits. Only once did writing make me feel something resembling or perhaps even surpassing happiness: I experienced a feeling of fulfillment when I finished writing The City in Crimson Cloak (2001; Eng. trans. Amy Spangler, 2007). It was as if I had lived my entire life up to that point to write this single book—it was as if everything had found its ultimate meaning. For once, I finally existed in my own story. To be sure, it was a short-lived “happiness,” transient, but it was real, incomparable.

Tokman: Cities have a special place in your heart; they draw you into a whirlpool and bind you with passion, and, of course, they finally push you to write. The most obvious fruit of this is your novel The City in Crimson Cloak. During a panel, you compared your relationship with Rio de Janeiro with that of a lover: you are bound with passion and, wounded, cannot leave. Having said that, have you ever thought of writing a novel about Istanbul, the city where you grew up?

Erdoğan: The protagonist of The City in Crimson Cloak is a city: Rio de Janeiro, the “river of Janus,” the double-faced god, one looking to the past, the other to the future. The city appears as a labyrinth set in more than two dimensions, as much in space as in time, both in the past and the future, full of dead ends, blind spots, terrifying echoes, uncanny prophecies. Rio is clearly a metaphor, the metaphor of both the outer reality and the inner world reflected upon it. In fact, the continuous clash of inner and outer worlds blurs our concept of reality. A metaphor of life as much as death.

Özgür, the other protagonist, the author of “The City in Crimson Cloak,” the incomplete novel within the novel, is a reinterpretation of the Orpheus myth whose Eurydice is her written self. Özgür means “free” in Turkish. I had gotten halfway through the novel when I found a name for her and realized the underlying dilemma, free will versus destiny. Özgür and Rio are face to face like two mirrors reflecting each other, but they are also dangerous opponents in a mortal chess game. Özgür’s own writing, the music that opens the gates of the Land of the Dead, continually carries death to life and life to death. The day I arrived in Rio, I realized that if this city had a myth, it could only be Orpheus.

But Istanbul, the city I was born and grew up in, is more difficult to construct such a mirror game for, requiring a much deeper confrontation. I was only thirty years old when I wrote that novel; two decades later, I feel I must traverse the path I had walked toward death, now back to life, until birth perhaps. I have been working on an Istanbul novel for years. For the time being, all I can say is that the abstract stone building whose cells and tunnels we entered in The Stone Building (translated by Sevinç Türkkan, due out in November from City Lights) will be among the metaphors of Istanbul.

Tokman: You were tried for terrorism in 2016 and imprisoned for about four and a half months. You were conditionally set free recently, but your international travel ban continues. During this time, an outpouring of solidarity on your behalf, both domestically and internationally, has advocated for your freedom. Briefly, what have you gained and lost in prison?

Erdoğan: For simply having my name listed on the totally symbolic “advisory committee” of a completely legal newspaper, the pro-Kurdish Özgür Gündem, my house was raided by police and I was imprisoned for 136 days with prosecutors seeking an aggravated life sentence against me. For the past five years my name has been on the advisers’ list, however, none of the hundreds of court cases opened against the newspaper have been relayed to me or other advisers such as linguist Necmiye Alpay, ecologist and Green Party founder Bilge Contepe, publisher and Nobel Peace Prize nominee Ragıp Zarakolu. The press law is clear: it states that advisers have no legal responsibility for a newspaper. In short, this is an entirely political case, an arbitrary and in fact unlawful arrest ordered from the top. Many people believe that it was an intended as a menace or a threat to all writers and intellectuals and to “white Turks” that meddle with the Kurdish business. A witch burning reminiscent of the Middle Ages . . .

Let’s face it: only in today’s Turkey is it conceivable to arrest on grounds of terrorism a female author—who writes existentialist novels and prose poems, has had her work translated into twenty languages, and received several national and international awards—on the pretext that she is a literary adviser to an oppositional but legal newspaper. Moreover, in my work as a columnist, which began with the leftist intellectual newspaper Radikal eighteen years ago and continued with eight different newspapers and magazines, never had a court case been opened against any of my articles, including those in Özgür Gündem, including those in my file as evidence today! I am aware that I have disturbed the state by tackling taboos like torture, rape and prisons, human rights violations, women’s rights, the Kurdish issue, and the Armenian genocide.

More than once I was fired, have received threatening phone calls for years, have been stigmatized and socially lynched. But it is outrageous to be charged with terrorism, especially if you take into consideration that I am a nonviolent person! In fact, as an essayist, I have been trying to construct a theory for nonviolence in a system that continuously produces violence. And I declared my conscientious objection three years ago; hence I refuse to bear arms! What is my actual, unforgivable crime? Trying to give voice to the victim . . . all victims . . . I have written about not only prisons and women and Kurds but also about African immigrants and racism, war and militarism, Armenians, street children, gays, Romani, Bosnia and Palestine, Primo Levi and Auschwitz. Trying to form a bridge between “us” and “the others” is my limited contribution and responsibility as a literary writer in shaping the individual and collective conscience.

What is my actual, unforgivable crime? Trying to give voice to the victim . . . all victims.

Being locked up in prison, suddenly, unexpectedly, completely unprepared, walls, walls, barbed wire, locks, handcuffs . . . I do not yet have the courage to ask myself how this heavy trauma has transformed me. There will be no consolation or compensation or possibility to reverse it. I accept and appreciate the awards as acts of solidarity, not only with me but with all the writers and journalists persecuted for their writing. I am perturbed by the fact that fame, which I had managed to avoid for such a long time, landed on me, and I am painfully aware of the irony in my work as a columnist overshadowing my literature. But I know very well that I couldn’t have stayed alive without this solidarity, and I am grateful for life.

A short story: under OHAL (the state of emergency), quilts, pillows, paintings, and flowers were forbidden in cell blocks, and potted plants were confiscated. Plants that were grown over a decade with such toil and perseverance were left to rot in the outer courtyard. A basil plant, hidden carefully inside a toilet, was discovered during the next military inspection. There is no soil in prison, no trees, no green, no color. First we produced the soil by drying tea leaves for weeks and adding eggshells as fertilizer, then acquired a few seeds. A tiny, quite ugly plant finally sprouted. We trembled over it, watering it with rainwater. He was the ward’s little prince! Unfortunately, he too was caught and sentenced to death. A few days before court, I apologized to my friends in the ward: “Now I understand what I have done by talking about suicide in my initial days. I’ve been reminiscing about death while all this time you have been struggling so hard to keep a tiny plant alive.”

Tokman: As a writer who is trying to be a tough advocate and a voice for those who have been alienated, how do you think violence and trauma will shape your writing henceforth?

Erdoğan: Since my first book, The Miraculous Mandarin, the story of a one-eyed woman, my writing revolves around themes like the wound, absence, and the void; death or the consciousness of mortality; loss, violence, disintegration; torture and betrayal. My main search has been how to tell the untellable, how to go as far as possible in the human experience carried to the utmost extremes. In my writing, the sacred and the profane stand side by side, sometimes in the same sentence, and the eternal unendingly overlaps with the transient. Even in my articles I have tried to stay within the boundaries of literature and only tell the untold, unheard stories of victims. I believe that without the voice or the scream of the victim, our word, hence our world, will be even more devoid of meaning. (But now I am a victim myself.)

While I was in custody, in an eight-square-meter cell with three other women, I often remembered my own sentences and metaphors. Will I ever be naïve enough to imagine the angel whose face was divided into two unequal parts by a scar (The Stone Building)? He had traversed the night of humans from one end to the other, arriving in the stone building, a police station, his hands full of presents. He had brought a gift for each prisoner. For one, a memory from childhood, for another, the smell of the sea, the sound of the sea or the wind for another. In which light or darkness will I encounter him once more? At which word will we run into each other? Will I be able to recognize his song, or will he be able to recognize his scar on my face?

Tokman: Do you think feminist rhetoric is foregrounded in your books? Do you have such inclinations as an author?

Erdoğan: I confess that until I read the wonderful analysis by the Austrian writer Ruth Kluger (who was also an ex-concentration camp convict) of The City in Crimson Cloak, I argued that I had deliberately chosen a bisexual, Dionysian language in this novel. However, apart from the music of Orpheus, Kluger also heard the song of Persephone, the queen and prisoner of the underworld: “Aslı Erdogan depicts a dangerous fall, a complete ruin, which so far in literature only men could live till the end, without compromising feminine sensibility and the female voice.” With this superb article, I was awakened to my night and realized how deaf I had been to the female voice within me. My next book, In the Silence of Life, was born of a late-discovered, painful encounter with this voice and a search for a female language. There is a great separation between the images and the reality of the condition of womanhood. Our “female” story is shaped from that abyss, the void. It is a feminist effort in itself to try to find a mirror or a voice for that abyss. Nevertheless, even in my less literary writing as in my essays, I stay clear from ideological, didactic, or academic approaches, from giving lessons, preaching. Writing is either a judgment or a scream. It is the scream that denounces violence forever.

Tokman: As far as I know, you started writing a novel before you entered prison, and part of this novel would describe a prison, but you have not written that part. Now that you are out, what is this novel about and when will it be finished? Have you ever worried about self-censorship?

Erdoğan: I have been working on an Istanbul novel for many years, and part of it takes place in prison. It is a strange coincidence, perhaps not so strange, that a torture scene very similar to the one I had imagined actually happened in the ward I was transferred to! Until today, only once did I cave in to self-censure. I did not publish a story I had written in the first-person voice of a rapist, himself a torture victim, for fear of offending rape victims. In short, I sacrificed my story for political correctness. But by now, I have learned that in writing there are certain themes into which you either never enter or, if you do, there is no compromise. Once you have passed the point of no return, and to confront violence, this is the point to be passed, there is no longer room for hesitation or hypocrisy or even pity. You have to push yourself and the reader, and of course the language, too, beyond all limits and borders.

Tokman: In In the Silence of Life, you talk about a battle with words, a writing that reaches nothingness when you are aiming to be everything, the blood that comes out of your body and flows through the language. It appears that your goal is to find peace in your writing from things that burden your life and make you unhappy. To what extent does this stymie or liberate you? Is it possible to redraw the boundaries between life and writing that do not overlap?

Erdoğan: Agony looking for voice, voice seeking image . . . stains of blood that leak out of the skin into the language, like a symptom of a hemorrhage hidden deep inside . . . sentences that disintegrate while trying to construct the bare texture of life, passages that arrive at nothingness while aiming to become everything. And then patiently trying to put the pieces together, once again, once “forever again.” Patiently trying to assemble together the night with the darkness, then filling it with silently waiting shadows, with cold, moist, and golden moonlight. In this book, I describe writing as such. A desolate awaiting, in absolute solitude. Waiting for the tolls of life, like a bell in which only words are resonating. But the title of the book already points to futility, to life that cannot be captured in words, silence that has never responded. As I wrote in The City in Crimson Cloak: Writing and life are like two ventriloquists facing each other and speaking from their bellies; I am no longer sure whose voice it is that I hear.

Writing: is it an interminable, persistent monologue, or is it a single-voiced dialogue between self and the world? Is it a testimony, a citadel in which we take shelter for observations or a duel with reality? Or is it simply footnotes we scribble to half-filled pages of life, “lies that lick our wounds” (The City in Crimson Cloak)? Is it essentially an act of survival, a vain quest for “immortality” centuries after the axe of mortality has struck our consciousness? Is it a liberation through catharsis, or is it our caste imprisonment? Is humanity not a constant prisoner of its own creations, stories, and myths? Referring to the same novel again, the writer had captured her own destruction in sentences like a fly captured alive in amber, turning it into a piece of art ready to be displayed and admired. Or is writing a rebirth, a resurrection whose path invariably crosses death, many deaths? I think it is all and yet none of these! Literature always needs to be masked when it is face to face with death, but if it keeps on breathing even when the masks are broken one by one—that’s what we call “literature.”

Tokman: I know you like to dance. In your writings we also hear the dance of words that are passed from ear to ear. I heard you did ballet while in prison. What kind of bond do you see between passion, authorship, and dance?

Erdoğan: Most readers are amazed by the fact that I was a particle physicist and completed a thesis on the Higgs-Boson particle. But they are equally perplexed when they find out that I have been dancing almost all my life, until my spinal surgery, with unwavering passion, from classical ballet to candomblé. The language in my texts, which I define as Dionysian and others have identified as corporal, physical, sensual, explosive, or musical, owes a lot to dance. It is through dance that I acquired the basic element of my language: the rhythm. From classical music, I learned the rules of counterpoint and harmony, which I applied while composing The Stone Building.

My body tells me when I have reached the ultimate limit, probed as deep as possible with words. At this point I leave my pen and begin to dance and cry! Every time I finish a book, my body shows strong reactions. I had two surgeries after my latest two books, and vice versa; I was fully recovered from a serious, two-year-long illness when I completed The City in Crimson Cloak. It is impossible to express in words the hidden wisdom of candomblé rituals. I learned that there is “something” there, something transcendental, before and after me, and only during rituals it might reveal itself to me. I am just an empty shell from which words flow, that’s it. Only in the moments of ritual, that is, while writing, can I hope life will flow through this empty shell.

April 2017

Translation from the Turkish

By Andrew Simes

Aslı Erdoğan is the author of nine books, novels, novellas, collections of short stories, essays, and poetic prose translated into more than twenty languages. Her texts have been adapted to cinema, theater, ballet, and acted in Milan’s Piccolo, among others. She has received various awards including the 2017 ECF Princess Margriet Award and the Erich Maria Remarque Award for peace.

Editorial note: For more, read a review of The Stone Building and Other Places.