New Voices in Vietnamese American Literature: A Conversation with Viet Thanh Nguyen, Andrew Lam, and Aimee Phan

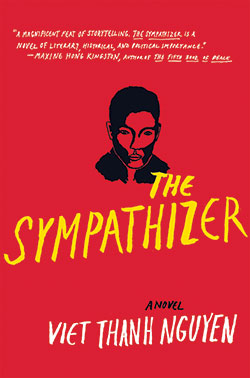

Viet Thanh Nguyen became the first Vietnamese American writer to win the Pulitzer Prize for his debut novel, The Sympathizer, this year. His achievement was particularly emotional and rewarding for the Vietnamese American literary community because for over two decades he’d been actively working with other writers and artists to promote Vietnamese literature and visual art and culture.

Here, Nguyen joins fellow authors Andrew Lam (East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres and Birds of Paradise Lost) and Aimee Phan (We Should Never Meet and The Reeducation of Cherry Truong) to discuss their writing, their inspirations, the diasporic Vietnamese literary community, and the future of Vietnamese American literature.

Aimee Phan: Although Viet’s debut as a novelist occurred last year, the three of us have been writing and participating in the diasporic Vietnamese literary community for many years. Could you share when you first realized you wanted to write creatively? What was your first story attempt about? Any failed first novels? How has your writing evolved?

Andrew Lam: I started writing after college, just about when the Apple Mac was created; I bought my first computer in my senior year at Cal. It was then that I, though a pre-med and biochem major, fancied myself a writer. My first attempt was to write about a failed romance, based on my own. While working at the cancer research lab, I took to writing—I suppose to make sense of what had happened. I bombarded mice mammary tissue with carcinogens during the day and watched the cancerous growth, and at night I gave myself to sadness. I wrote. But you discover soon enough that if your heart is still breaking you cannot give a proper framework to the story of a broken romance. So I gave up that story and wrote about my Vietnamese childhood and the war, and my memory of being a refugee. Eventually I got better at writing, bored with science, and so I decided to go into an MFA program. I wrote short stories, mostly because they fit my temperament. And yes, there’s a failed novel somewhere on a floppy disk that I haven’t looked at in over two decades (can one still access an antique floppy disk, I have no idea?), but I am writing a new one now.

As a journalist my subject matter ranges from environmental concerns to immigrants’ rights, from scientific discoveries to shifting human behaviors due to the advent of communication technology, from the ongoing refugee crisis to the current political climate in the US—which is to say everything under the sun. My literary work, however, such as in Birds of Paradise Lost, remains focused on the story of the migrant, the refugee who crosses all kinds of borders—both in the sand and in the mind—and his or her struggle to remake themselves. That hasn’t changed, but the years have deepened my understanding of myself and my own identity in relationship with others, and maybe the nature of my own heartbreaks and how this continues to inform me as I write.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I have been writing on and off, mostly off, since I was in the second grade. I wrote my first short story in high school, and all I remember of it was that my teacher commented on my “purple prose.” I became more serious in college when I got into Maxine Hong Kingston’s creative nonfiction seminar at Berkeley. But by the time I graduated, I knew I was a better scholar than creative writer, so I went to get a PhD and wrote fiction on the side. I wrote short stories because I thought they would be easier and I could get them done in the crevices of time I had. Turns out they were pretty hard, and I spent a couple of decades writing them, with real attention beginning after I got tenure. That time after tenure when I focused on writing short stories (while still doing my academic research) was very hard and taught me how to write, persist, endure. It was great preparation for writing a novel.

The short stories were about Vietnamese refugees and the people they left behind or encountered. When it came to the novel, I felt that I didn’t have to continue that subject. Plus there were writers who had already published books about them, like Andrew and Aimee. So I focused on the war itself and its aftermath in the novel. The novel’s style is radically different from the short stories, which were mostly in the standard realist vein. I think I could do something quite different because the form was much more expansive and natural and because I had already done the realist thing and wasn’t happy with it.

I wrote short stories because I thought they would be easier and I could get them done in the crevices of time I had. – Viet Thanh Nguyen

Aimee Phan: How has your perspective and relationship with literature and writing changed? How do you see diasporic Vietnamese literature today, compared to twenty years ago, when we only had a few writers publishing? And how do you see diasporic Vietnamese writing positioned in contemporary world literature?

Andrew Lam: When I started out writing, there were very few people who looked like me and who came from the same background in the field. Actually, there were but one or two Vietnamese American journalists—that was it. When I started getting published, I remember there was a sense of delight and then dread: everyone in my community wanted me to tell their stories, their sadness and anguish, my family members included. It became overwhelming at times: “Why don’t you say this . . .” my mother would lobby me. “How can you say that; that’s not right,” my uncle would say. I was a bit of a lone voice out there then, and the community, so long invisible and marginalized, wanted me to be its spokesperson, and it didn’t feel good. Now, of course, there is a chorus of voices, and so many marvelous angles and views on the same story, and it gives rise to a collective work that is rich and powerful.

I think my writing changed fundamentally compared to when I started a quarter of a century ago. When I started writing, I wrote with a burden of memories, with a deep yearning to share the travails and struggles of the Vietnamese people in the aftermath of the war, both at home and abroad. In a sense I played both the role of an advocate and that of a writer. I think you can see elements of that in Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora. But somewhere along the way, I fell in love with the craft itself, and literature, and the power of the English language. In a sense, the activist in me has yielded to a more literary voice that is more dispassionate, and discerning. In fiction, especially, I like to create characters who have their own free will—that is, are self-directed, and do things that may appall or delight me but are chiefly being true to themselves and not my political agenda. That was something I couldn’t do at the beginning of my writing life. Vietnam, the diaspora, the refugee experience may still dominate the theme, but the craft sure shifted since 1990.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Before The Sympathizer, I was focused mostly on trying to figure out how a short story worked. I was certainly concerned with questions of history, politics, and theory, and I was dissatisfied with the form of the short story itself. But I had started a project with writing short stories and I wanted to finish it, which meant finishing and publishing a short-story collection. So the history, politics, and theory were secondary until I could just figure out how to write a damn short story. When it came to the novel, all of a sudden the struggle with form was overcome. It was still challenging, but not deeply frustrating as it was with the short story, and because I wasn’t so much worried about form, I could suddenly see how to deal with history, politics, and theory.

Diasporic Vietnamese writing has grown during the same period I have, and we are now seeing more younger writers, as well as writers our own age or thereabouts, who are not writing about the war. Bich Minh Nguyen, Vi Khi Nao, Phong Nguyen, Dao Strom. Of course, some are still writing about the war and its legacies, but in new forms like the graphic novel—GB Tran, Thi Bui—or genres, like Vu Tran and the detective novel, or Dao and experimental mixed genres. Or getting big acclaim, like Ocean Vuong in poetry. It’s really a growth field that does and doesn’t adhere to the history of the war. It’s not predictable in some ways, and that’s good. Insofar as positioning this literature globally, that’s beginning to happen with writers who have some measure of international reputation, like Monique Truong. I’m not sure we have a global Vietnamese writer yet, whereas we have global Indian diasporic writers, for example.

Aimee Phan: I’m specifically thinking about Barack Obama’s recent visit to Vietnam. Whenever the relationship between Vietnam and America is in the global media, Vietnamese American writers are asked to give their thoughts on historically and politically fraught issues. This is a responsibility the two of you have not shied away from. How do you think contemporary Vietnamese American writers can help influence the conversation on the relationship between the two countries?

How do you think contemporary Vietnamese American writers can help influence the conversation on the relationship between the two countries?– Aimee Phan

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I’m carrying this conversation out on my Facebook author page, where the majority of the followers are Vietnamese people in Vietnam. I write in English; the discussions/debates are in English and Vietnamese. These people have followed me because of the Pulitzer news, and most of them haven’t had the chance to read the novel yet. I’m not sure what they expect of me, but I use my posts on topics like April 30, reconciliation, the Obama visit, and the controversy over Bob Kerrey’s appointment to be chairman of the board for Fulbright University Vietnam to articulate what I hope are critical stances that oppose all forms of power. So with the Obama visit, I did point out the theatricality of it, the feel-good nature of it versus the problematic issues of lifting the ban on selling arms and maneuvering into an alliance with Vietnam to contain or restrain China. Some Vietnamese people agreed; others are ready to follow the American model of capitalism and power.

But as Andrew points out, these efforts on social media or on the occasionally translated work can only impact a small audience. We need our entire books available to the Vietnamese-language audience in Vietnam. The Sympathizer is in the process of being translated, but I don’t know yet how good the translation will be, or whether it can pass censorship unscathed. I won’t allow it to be published in partial form in Vietnam, so if it is censored, I will have to get it out online. Maybe because of the Pulitzer press, readers will actually want to read it even if it’s not in a bookstore. My nonfiction book, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, will be translated into Vietnamese, too, and will face the same issues. But in that case, the publisher is talking about having me in Vietnam. Perhaps if that happens, it can be part of the détente Andrew talks about with a literary exchange in Vietnam.

But as Andrew points out, these efforts on social media or on the occasionally translated work can only impact a small audience. We need our entire books available to the Vietnamese-language audience in Vietnam. The Sympathizer is in the process of being translated, but I don’t know yet how good the translation will be, or whether it can pass censorship unscathed. I won’t allow it to be published in partial form in Vietnam, so if it is censored, I will have to get it out online. Maybe because of the Pulitzer press, readers will actually want to read it even if it’s not in a bookstore. My nonfiction book, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, will be translated into Vietnamese, too, and will face the same issues. But in that case, the publisher is talking about having me in Vietnam. Perhaps if that happens, it can be part of the détente Andrew talks about with a literary exchange in Vietnam.

The Sympathizer is in the process of being translated, but I don’t know yet how good the translation will be, or whether it can pass censorship unscathed. – Viet Thanh Nguyen

Andrew Lam: I voted for Obama, wrote lovingly about him, but frankly I was disappointed with the visit. I am quite aware of the incredible soft power he exuded while there—the ultimate charmer saw tens of thousands lining the street waving American flags. That’s quite something. But to me his seeming indifference to the Vietnamese struggle for true political reform while giving public lip service to human rights is damaging. Selling lethal weapons without any implemention of human-rights reform will only encourage Hanoi to continue its crackdown on dissidents and human-rights activists with no fear of international criticism or, for that matter, US rebuke. It also sends a message to political reform advocates that they cannot hope to look toward Washington for support. A growing civil society without international support and limelight will be a struggle under a police state.

My work has been translated into Vietnamese and published in newspapers in Vietnam when the government deemed them positive writings about the country, but most of my criticism remains stuff written in English with occasional Vietnamese translation from Vietnamese ethnic media in the US. So many now in Vietnam read in English and use Facebook—people who friend me these days are young, educated Vietnamese from Vietnam, people who read international writing—and it’s in them that I see a sliver of my work playing some small role of debate and the exchange of ideas. But unless our work is translated and allowed to be published in Vietnam, it’s hard to imagine how we can really have a direct conversation with the people of Vietnam.

On the other hand, I do work with some members of Congress on human-rights issues and behind the scenes with organizations who fight human trafficking in Vietnam. I’d love to see a growing civil society to the point where a Vietnamese American writers’ panel is allowed at a book festival in Hanoi. But that day seems very far away.

I’d love to see a growing civil society to the point where a Vietnamese American writers’ panel is allowed at a book festival in Hanoi. But that day seems very far away. – Andrew Lam

Aimee Phan: Who are the Vietnamese American writers we should be reading now?

Andrew Lam: All of them. But I think we should expand that question to “who are the Vietnamese writers and artists and filmmakers we should be watching around the world?” That is, what is new and exciting about the diaspora and its artistic expression? There are fabulous loners who escape the collective radar but are making strides. There’s an artist named An-My Lê whose photographs of landscapes transformed by war or other forms of military activity are layered with all sorts of meanings. She won a MacArthur Fellowship. Binh Danh is another artist whose work hangs in the de Young and Corcoran and several other museums in the US and whose imprints of war images on leaves are breathtaking. There are cartoonists and documentarians like Dustin Nguyen who worked with DC Comics, and Marcelino Truong in Paris whose comic book, Such a Lovely Little War, was recently translated. Duc Nguyen is a filmmaker who won a couple of California Emmy Awards for Bolinao 52, about boat people who committed cannibalism to survive. And Chinese Vietnamese filmmaker James Chan just did a documentary of Chinatown, which is to say, not every topic has to be about war and memories of war. Then there are those returning to Vietnam to create a vibrant community of artists’ collective there, and under the support of the world-renowned artist Dinh Q. Lê, whose work hangs in the MoMA in New York City and whose first solo exhibition was at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo.

There are also rappers and filmmakers and avant-garde artists in Vietnam as well. Did you see twenty-six-year-old rapper Suboi at a town hall meeting with Obama? I’ve seen her YouTube videos. She’s dynamite. In a sense, I envy places like Taiwan and Singapore and Japan, where diasporic artists are welcomed home with open arms to exchange ideas with local artists and vice versa. But it’s a fledgling community. A communist state like Vietnam remains wary of “foreign influence.” My friends tell me they read Perfume Dreams via pirated versions sold on the street. But when it rains, the ink melts away. Kind of sad, kind of poetic.

You know what I would really love to see? A kind of literary/art journal that chronicles the arts of the diaspora, something like 100 Flowers Blooming with smart literary criticism and reviews and interviews thrown in. And let’s throw in some amazing translations as well. It’s something diacritics.org is doing but on a much larger scale. If I were a multimillionaire, that’s one of the things I would fund.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I mention them above. I’ll highlight a few who aren’t so well known right now, because they are doing such innovative or unusual things, or their works have just come out or are coming out. Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do is a graphic memoir about the artist becoming a mother and reflecting on her own parents, who lived through decades of war and unrest in Vietnam and then became “boat people.” I found this book easy to read (it’s all pictures!) but also really painful to read. Anybody who’s had a parent traumatized by war or being a refugee and can’t communicate with them and is puzzled by their history—or really just anybody who’s interested in human stories—is going to be affected by this book. Vi Khi Nao’s Fish in Exile is a strange novel about two people who lose their children in a tragic accident. It’s got nothing to do with Vietnam or Vietnamese Americans, and a great deal to do with Greek myth, tragic drama, and literary experimentation. It’s hard to forget and perhaps challenging to understand. In short, it’s not “ethnic literature.” Phong Nguyen’s The Adventures of Joe Harper also undermines notions of Vietnamese American literature, if we define that as what is written by a Vietnamese American. It takes up the story of Joe Harper, a minor character in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and imagines a world where Tom Sawyer ran off to become a pirate and a cold-blooded killer. Like Bich Minh Nguyen in Pioneer Girl, Phong claims an inheritance in American literature, not Vietnamese.

Aimee Phan: I’m interested in this idea Viet brought up of the global Vietnamese writer—which hasn’t quite emerged yet but seems inevitable. I’m also interested in seeing how Vietnamese writers begin to further engage in each other’s work, as Vietnamese visual artists have already been doing. Viêt Lê, a visual artist and fellow DVAN member, has curated exhibits and galleries featuring Southeast Asian artists, which has created great opportunities for a variety of visual artists to come together. Recently, a group of Vietnamese American women writers, under the inspiration and leadership of writer Dao Strom, has begun collaborating on projects called She Who Has No Master(s), with the mission of reaching out to other Vietnamese women writers and artists around the world. I am surprised by how inspired I’ve become by working with these other women whom I’ve admired and read for many years—and it has influenced my writing in unpredictable and rejuvenating ways. So many writers consider the craft to be a solitary act, so it certainly isn’t for every writer. You are both very active in the Vietnamese American community as well as other literary and artistic communities. Do you find inspiration in your colleagues’ and friends’ work? Have you ever worked on an artistic collaboration with other Southeast Asian artists or writers? Would you consider collaborating with other Vietnamese writers or artists in creative work? What are your future projects?

Andrew Lam: I went to creative writing school at San Francisco State University in 1989, and it was a big learning curve. But I was the only Asian American in the entire school besides a Chinese American cartoonist. My parents were shocked when I didn’t go into medical school. “Name for me a Vietnamese who’s making a living writing,” my father, who has an MBA, said. I couldn’t really name anyone. That’s different now. I can name a few. But in terms of being part of a writing collective, I don’t belong to any at this point. In nonfiction, however, my work usually is commissioned or freelanced, and usually I work with an editor. At New America Media, where I am an editor, I work with my colleagues on various journalistic pieces. But in fiction, alas, I work alone for the most part. In the works? Another collection of short stories and a difficult-going novel about a young man struggling to find a place to call home in the floating world, which is all the more reason to try to work through it.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I’ve been active in political, arts, and literary organizations since I was in college, and have always believed that literature cannot effect social change on its own. It can only do so in conjunction with political and cultural movements. That was a major reason for my activism and my continual investment in DVAN and our blog, diacritics.org, the leading online source for Vietnamese and diasporic arts, culture, and politics. At the same time, it’s always hard to balance that kind of work with one’s writing, not to mention one’s life and other commitments (like a job). And at the moment, I think The Sympathizer probably has more impact on the world than all the activism I’ve done. But again, part of that impact came from its arrival in a world that had already been shaped by earlier activists. So I am still trying to figure out the right balance between investing time in my own work and collaborating with others.

I have a short-story collection coming out in February 2017, The Refugees, about Vietnamese refugees and Vietnamese Americans. And I’ve written the first fifty pages of The Committed, the sequel to The Sympathizer, with an excerpt published in Ploughshares and another forthcoming in Freeman’s.

June 2016