“A World of Sharp Edges” A Week among Poets in the Western Cape (part 2)

Part 2 continues with highlights from the “Dancing in Other Words” festival; if you haven’t read part 1 and would like to read the entire essay, click here.

On our way back to Spier for the festival proper, we stopped off at the University of the Western Cape, where Antjie Krog had arranged for the poets to read to the students during lunch hour alongside younger practitioners working on their craft at the university’s creative writing program. The auditorium was packed, standing room only. One by one, Tomaž Šalamun, Ko Un, Yang Lian, and Joachim Sartorius read their poems, but it was perhaps Carolyn Forché’s “The Colonel”—part of the sequence of poems inspired by her time in El Salvador—that provoked the most visceral effect that afternoon:

WHAT YOU HAVE HEARD is true. I was in his house. His wife carried a tray of coffee and sugar. His daughter filed her nails, his son went out for the night. There were daily papers, pet dogs, a pistol on the cushion beside him. The moon swung bare on its black cord over the house. On the television was a cop show. It was in English. Broken bottles were embedded in the walls around the house to scoop the kneecaps from a man’s legs or cut his hands to lace. On the windows there were gratings like those in liquor stores. We had dinner, rack of lamb, good wine, a gold bell was on the table for calling the maid. The maid brought green mangoes, salt, a type of bread. I was asked how I enjoyed the country. There was a brief commercial in Spanish. His wife took everything away. There was some talk then of how difficult it had become to govern. The parrot said hello on the terrace. The colonel told it to shut up, and pushed himself from the table. My friend said to me with his eyes: say nothing. The colonel returned with a sack used to bring groceries home. He spilled many human ears on the table. They were like dried peach halves. There is no other way to say this. He took one of them in his hands, shook it in our faces, dropped it into a water glass. It came alive there. I am tired of fooling around he said. As for the rights of anyone, tell your people they can go fuck themselves. He swept the ears to the floor with his arm and held the last of his wine in the air. Something for your poetry, no? he said. Some of the ears on the floor caught this scrap of his voice. Some of the ears on the floor were pressed to the ground.

May 1978

The girls sitting on either side of me squirmed at the sound of the colonel spilling the human ears on the table. Once Carolyn was finished reading, the one on my left, albeit still visibly shaken, clapped, while the other held her hand over her mouth.

*

May 10 and 11. The festival was finally upon us. As Marlene later commented, much to the spectators’ mirth, many of us had stumbled back to our rooms each evening rather tipsy—our hosts being so generous they had literally loaded half the bus with crates of wine so that our gullets wouldn’t run dry throughout the road trip—so despite our high-spirited conversations, it remained to be seen whether they would assemble into anything resembling a coherent thread. It was only natural for there to be some doubt in that regard. There were to be four panel conversations over the course of two afternoons, and the titles were certainly imposing: (1) Lost in translation, found in poetry: A master class in translation; (2) What has ethics got to do with it? Does poetry open a way to an awareness of being and dignity in the processes of political and cultural transition?; (3) Is the world decayed metaphor? Does poetry shape the world, or is it but a pulse beat of reality?; and (4) Is there a South African Way to the great Nowhere? We filed into the Spier Manor House and began.

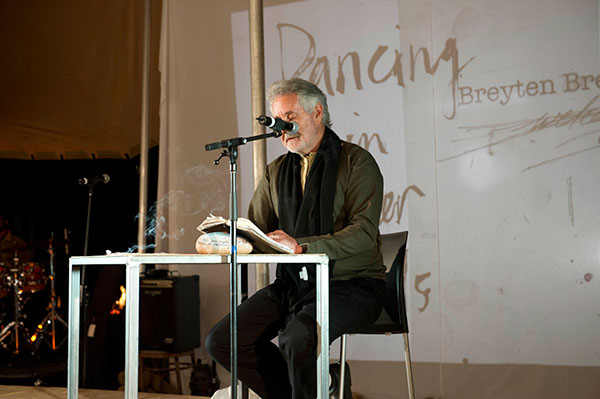

Gunther Pakendorf, the moderator of the first panel, which I was to sit on, thankfully began the rather daunting proceedings on a humorous note, reading his translation of “The Festival of Poets,” from Breyten’s latest collection, Katalekte:

look at the poets

they come from torn countries

with coals in their eyes

and drizzled dandruff on collar

and sleeve, some have folded flags

of commitment in four parts

for confinement and condensation

of a text in a slim volume

which they will be mumbling in the limelight from the podium

to a sparse audience who understand nothing

look how dancing with clumsy little steps

they try to encircle and enchant each other

how in romantic delusion

they seek seduction in the body of the other

how messy and short-lived and lonely

is love

listen how they listen to each other

reading from poems

as if it were the most important news tonight

that will flit away tomorrow morning

like a bat into nothingness

rock-bye-baby in the treetop

look how they regale each other

with well-shaped turds of sound,

a family row, unfaithful lovers,

forgotten fathers, a touch of suppression,

the yearning for silence in the soil

look how the poets drink

the drinks paid for by others

observe their worn-out shoes

the lipstick applied short-sightedly

how on the toilet they try to solve

the crossword puzzle from the paper

left free of charge at the hotel door

look how the poets remember the names

of the one and the other who was still here

last year leaning on a crutch

or drunk in the passage, having wet their pants

look how important the poets are

each before their own mirror

when the light from the bulb is weak

look how flat are their wallets

look how importantly they take their leave

to disappear into the real world

invisible like beggars

with secret instructions

whose voices should not be heard

Gunther had set Tomaž, Marlene, and me the task of translating two poems into our respective languages—Tomaž in Slovenian, Marlene in Afrikaans, while I was given the choice of either Italian or French. The poems he selected were Philip Larkin’s “This Be the Verse” and Wopko Jensma’s “In Memoriam, Ben Zwane.” Although the poems were well chosen—and perhaps well translated (I can’t comment on that due to my lack of any Afrikaans or Slovenian), while Bill Dodd’s Italian translation of the Larkin was certainly outstanding—the discussion only really got going once it shifted to the real crux of the matter: the arguments in favor of either a literal or an interpretative translation. The panel was evenly split. While Gunther and Tomaž were in favor of literal approaches, Marlene and I both agreed that, as she put it, “normative strictures are to be avoided.” Marlene’s resistance to the concept of a standard, faithful translation, as she commented, was due to the fact that although Afrikaans had never throughout its history been a fixed language—on the contrary, constantly evolving and absorbing—it had become standardized by the high priests of apartheid, and she was glad that de-standardization in the wake of 1994 could finally begin. Fascinatingly, Tomaž pointed out the cultural dividing line that can sometimes be seen in the context of translation: while the French tended to favor imitations, the Germans almost always opted for literal renditions, thus meaning definitions of what constituted a “good” translation would vary from country to country. From the audience, Victor Dlamini, a journalist, spoke of how indifferent many South Africans were to the importance of translation, noting that white, English-speaking journalists working at The Star, a leading Johannesburg tabloid, would spend decades visiting Soweto to write up their stories and yet never bother to learn the languages spoken there, isiZulu and isiXhosa, relying instead on interpreters. Next came Leon de Kock, a poet and translator—notably of Marlene’s Triomf, who was of the opinion that South Africa is living in a state of “multi-lingual contestation.” Stressing that languages do not “rainbowishly” live together in his country, how, he asked, does one transpose the energy of the agonistic literary act and still replicate the emotional, cultural, and sonorous registers? Translating poetry, he argued, allowed for a greater freedom than translating prose, enabling the translator to attempt a “licentious” adaptation as opposed to a “licensed” translation. Leon argued there was room enough for many translations in many different styles and that this would in turn expand our culture, which I wholeheartedly agreed with. Again, it seemed the concept of mutually annihilating truths coexisting entirely amicably, as Rian Malan had put it, was a South African specialty. Although it was a fascinating discussion, it was further proof that the topic of translation is still rather nebulous or, rather, a completely open field, where definitive answers are largely impossible. A case in point—Tomaž regaled us with a bizarre statistic: although writing in a language spoken only by two million people and hailing from a land that is by all accounts a political backwater, there are currently more translations available by Slovenian poets in the United States than by Italian or German poets combined.

What has made The Country of My Skull a classic is that while Krog records horrors, testimonies, and conversations, educating the hearts of her readers as much as their minds, time almost ceases to exist.

After a short break, it was time for the second panel—What has ethics got to do with it? Does poetry open a way to an awareness of being and dignity in the processes of political and cultural transition?—which to my mind had the greatest potential for controversy and crossed wires, if everything went well, or if not would probably wind up being completely pointless. Conversations on the topic of ethics can often evaporate into a cloud of high-minded pieties, but with Antjie Krog on board, we were at least guaranteed a handful of reality checks. Probably best known outside South Africa for The Country of My Skull (1998), Krog’s very personal—and yet public—history of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, where as part of the South African Broadcasting Corporation’s radio team that covered the proceedings, she painstakingly recorded the agonizing statements put forward almost on a daily basis by the victims (and perpetrators) of apartheid over the course of two years, from 1996 to 1998. Part of what made The Country of My Skull so distinctive was that Krog constantly resisted the temptation of wallowing in self-absolution and self-consolation, which many writers covering such events ultimately succumb to. Instead, her words, like pixels on a screen, slowly assemble a picture of the “big South African tongue of consciousness” as it gropes “towards a broken tooth”—and this despite the mounting dichotomies directly or indirectly unveiled by the TRC, perhaps one of the most resonating being: “If I write this, I exploit and betray. If I don’t, I die.” Yet what I believe has made that book a classic is that while Krog records horrors, testimonies, and conversations, educating the hearts of her readers as much as their minds, time almost ceases to exist. Martin Versfeld’s lines on love, from that book Breyten had handed out, summed it up: “To love is to have time for somebody or something . . . . Another word for this is caring, that little bit of extra absorption in what you are doing that makes you forget clock time.” As Dele Olojede, the Nigerian journalist, introduces the speakers, beginning with Yang Lian and Albie Sachs—who not long ago retired after fifteen years as a judge on South Africa’s Constitutional Court—by the time he turns to Antjie, her discomfort is already palpable. “Antjie Krog is a figure of tremendous fascination for me,” Dele says in his bassy voice, “because she is guilty of feeling too deeply about this country. Perhaps as poets are wont to do.” At which Antjie leans into the microphone—“I thought you were going to say that like many people in this country I feel too guilty.” Many in the audience laugh, perhaps a little nervously, since Antjie might as well have been referring to their guilt: everyone here is white, middle aged, and middle class; despite their likely liberal stances, they are nevertheless the direct beneficiaries of apartheid.

Dele asks the speakers to voice their thoughts on the potential of poetry to take us through the many challenges that societies in transition face. Quite appropriately, Yang Lian begins by mentioning how privileged and moved he felt at being given the chance to see the country before speaking about it. Although it is a beautiful country, he says, he perceived it as a “stormy ocean.” Poetry is fueled by the passion to ask questions, he says, and this transcends all ethnic, religious, or linguistic divides. “We’re in diamond country!” Yang exclaims with a grin, and suggests that the poet’s task is to burrow tunnels into the self so as to ask those uncomfortable questions. “If reality is an ocean, culture is the boat, and poetry is the ballast that keeps the boat steady in the right direction through the storm.” Dele passes the conch over to Antjie who sighs, “I have to say I only have problems . . . if we use the boat metaphor, then I feel I see a hundred boats on a stormy sea in South Africa and they’re all going in different directions. . . . I feel I’m in a country that has a fractured morality; one that is deeply confused about what its ethics could and should be, even what ethics is. The ethics in which I was raised proved to be a failure. Now you have to relearn. But there are several barriers that prevent this engagement.” Antjie singled language out as one of the principal obstacles.

She is of course correct. Although poets and writers may rise above apathy by using words both ethically and responsibly, this does not matter much unless those words are then propagated or, in a country like South Africa—with eleven official languages—properly translated. Krog spoke of how translations—and by extension translators—are not encouraged, respected, or rewarded. This is also true. While I translate four to five books a year, I barely make enough to cover the rent, and this is thanks to the availability of grants and schemes that are simply nonexistent in South Africa. Yet is this surprising? One cannot expect translation to be held in high regard when books themselves—regardless of whichever language they’re printed in—are no longer read or sold. Politicians certainly don’t read. That much is clear—in fact, they actively encourage their voters not to. “I don’t have time for fairy tales,” David Cameron told an interviewer when asked about what he was currently reading upon taking office, obviously seeking to reassure his voters that culture would not get in the way of his merciless war on the poor and immigrants, while Ed Miliband, leader of the opposition, sheepishly followed suit and parroted a similar philistinism, obviously fearing he might hemorrhage support if he dared come across as a “reader”—let’s remember that this is of course a man who started wearing contacts the moment he set his eyes on leadership of the Labour Party, as though twenty-first-century England had suddenly turned into Pol Pot’s Cambodia, where bespectacled people were executed for looking like intellectuals. Addressing the problem of the engaged intellectual’s difficulties in breaking through the marketing-driven concerns of publishers, Krog quipped: “People are constantly interviewing you to hear what you think instead of reading what you write.”

Olojede then turned to Albie Sachs. “Even though I’m a judge,” he said, “I’m often accused of being a poet,” and though he resisted the appellation—perhaps all too humbly as Sachs has arguably written some of the finest prose ever seen in the legal profession—he then spoke admiringly of the poet’s role as a bridge-builder. “My own attempt to build a bridge in relation to different concepts of ethics across various communities,” he continued, “led to that bridge collapsing into the water, and I couldn’t swim very well with one arm . . . it was a saddening experience.” There is a passage in Jacques Pauw’s Dances with Devils: A Journalist’s Search for Truth where the journalist comes face to face with Pieter Botes, a former member of the SADF death squad that masterminded the car bomb that led to the loss of Sachs’s arm. Pauw meets Botes for dinner at a hotel and is left dumbstruck when his interlocutors exclaims, “I made a little sauce out of Albie’s arm” while chewing on a chunk of steak. “Was it a success?” Pauw asks, and Botes replies: “You know, in a war it’s sometimes better to maim the enemy than to kill him. We knew that everywhere Sachs went in Maputo, people would see the stump where his arm once was and say: ‘Look, the Boers blew it off,’ knowing we could do the same to anyone we chose.” In The Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter, Sachs tells us how around the time of the TRC, each month would bring new information about who his would-be assassin might have been, and although several likely candidates emerged—Botes being one of them—the identity of that person ultimately didn’t matter, and that if such a person should come forward, what he would most want would be for him “to contribute towards the building up of the country for the benefit of all who lived in it.”

“Was it worth it?” The question seems to repeat itself ad infinitum. As if picking up on this, Dele asks: “Is anybody listening when the poet is talking? Doesn’t it sometimes feel as though they aren’t?” While Yang Lian spoke positively about his experience of translating a Uyghur poet and how this process enabled them to see past the animosity that has often characterized the relationship between the embattled, Turkic-speaking Uyghur minority and the Chinese government, Krog opined that whether people listened or not wasn’t so much the issue, but that the literature on offer was not rooted to the reality it was meant to describe: “What is really happening in this country is being said in other languages . . . we are an illiterate country. There are many people who can’t read. Broken English is this country’s official language,” at which the audience clapped and giggled knowingly. On a concluding note, Krog stressed that a writer should not concern themselves as to whether they are read or not, since “one writes so that you don’t die of shame, that you didn’t say something when a girl is cut up somewhere in a parking lot and raped. . . . You know that a poem will achieve nothing, but at least you will get through the night.”

As the sun set, the festival attendees flocked into the tent that had been erected in the main courtyard, where Marthinus Basson, the renowned theater director, choreographed the readings given by Šalamun, Ko Un, van Niekerk, and Müller on the first night, and Krog, Breytenbach, Forché, Sartorius, and Yang Lian on the second, with Neo Muyanga leading the musical component. In lieu of writing about the reading, which was an experience that would hardly translate on the page, I thought I would instead select two poems from that night, Ko Un’s “A Certain Joy” (on the left) and a section from Tomaž Šalamun’s “Eclipse” (on the right):

What I am thinking now

is what someone else

has already thought

somewhere in this world.

Don’t cry.

What I am thinking now

is what someone else

is thinking now

somewhere in this world.

Don’t cry.

What I am thinking now

is what someone else

is about to think

somewhere in this world.

Don’t cry.

How joyful it is

that I am composed of so many I’s

in this world,

somewhere in this world.

How joyful it is

that I am composed of so many other others.

Don’t cry.

I will take nails,

long nails

and hammer them into my body.

Very very gently,

very very slowly,

so it will last longer.

I will draw up a percise plan.

I will upholster myself every day

say two sqaure inches for instance

Then I will set fire to everything.

It will burn for a long time.

It will burn for seven days.

Only the nails will remain,

all welded together and rusty.

So I will remain.

So I will survive everything.

*

The following afternoon, the third panel—featuring Carolyn Forché, the Dutch poet Alfred Schaffer, and Joachim Sartorius—assembled to discuss the topic: Is the world decayed metaphor? Does poetry shape the world, or is it but a pulse beat of reality? As the chair, Kole Omotoso, the Nigerian novelist and academic, started the conversation by asking Carolyn to regale the audience with a theory concocted by the German poet and “public nuisance,” Hans Magnus Enzensberger: “When Enzensberger wrote of the twilight of the literary public sphere, he claimed that literary culture is reduced to the simple reading of pleasurable texts by the true, actual public, a minority of ten to twenty thousand people. Enzensberger later reduced this estimation, stating that lyric poetry could only really count on a readership of +/- 1,354, meaning that a good poet can count on exactly as many readers in Iceland as in the United States”—probably explaining why, as Carolyn pointed out, Enzensberger’s first collection in English was entitled Poems for People Who Don’t Read Poems. “Yet,” Enzensberger said, “our seemingly anachronistic art form somehow always manages to surprise us.” Explaining that the so-called Enzensberger constant is quite well known in Germany, Joachim Sartorius also added that however minuscule a poet’s audience, by speaking in very intimate and subjective ways, poets nevertheless become the repositories of essential human qualities that would otherwise go lost. “Does poetry shape the world?” Sartorius admitted that shape was a very big word, especially in view of these 1,354 readers, and that the answer would vary from country to country. To clarify his point, he brought up the international festival held each year in the Colombian city of Medellín—Pablo Escobar’s former stomping ground—where he’d gone to read his poetry in the late 1980s, back when the city was deemed one of the most violent places on Earth. At the end of the festival, the organizers had distributed a questionnaire, which was headed by the following query: “Does poetry heal the wounds of the city?” “This is a question no German festival organizer would ever dream of asking!”

Following on, Carolyn Forché spoke of her work as a human rights activist in various countries and how her poetry, formerly of a personal and intimate nature, had been radically transformed by the events she witnessed, leading to accusations from several quarters that she had become a “political poet.” “Being accused of being a political poet,” she stressed, “is not a happy situation in the United States. One must not be a political poet!” As one of the few contemporary poets who appears refreshingly unperturbed by the usual academic theorizing as to the definition of—and boundaries between—the private and the public, the personal and the political, Carolyn seems to perceive the act of writing poetry as simply, borrowing a line from her Blue Hour, “opening the book of what happened.” Language, she explained to the audience, cannot help being permeated by the experiences we are subjected to: “Everything that happens to mark us as a result of our experience, burn us, perforate us, change us, wound us, enlarge us, it also does to our language. Writing in the aftermath of such experience, whether implicitly or explicitly, the experience itself becomes somehow legible, traceable, there and present on the page.” Carolyn then suggested that with the “acceleration of the velocity of experience due to technological advances, our take on reality has become a high-speed flickering, and what poetry does, whether we read or write it, is to slow us down, enabling us to increase our capacity to sustain contemplation. It’s one of the greatest methods for increasing this capacity. It will be essential for our future survival.” This brought to mind a couple of questions Breyten had asked in a piece penned for the French daily Libération a couple of years ago: “Have we gained anything from knowing more, and instantaneously, about what is happening in the world? Are we being given to understand or are we solicited to partake of the race for drama beamed and blared by the media?”

I entered the hall to attend the fourth and final panel of the festival somewhat hesitantly. The topic was Is there a South African Way to the great Nowhere? The discussion features Antony Osler, a Zen monk and poet, as well as Ko Un and Petra Müller. While some found the nebulousness of the question beguiling, I most certainly didn’t. Although I admittedly knew little about Zen philosophy, having read only a handful of texts (mostly works by Gudo Nishijima and D. T. Suzuki) I had often been put off by the way Zen appeared to encourage moral detachment from the world and how its tenets, although nearly always poetic, in fact appealingly so, seemed to resist concrete verbalization. It had always struck me as too complacent a theory or, rather, a way of life. A few months before heading to South Africa, I had read Arthur Koestler’s Drinkers of Infinity, where Koestler had spoken of the dichotomies between Western and Eastern thought in the context of the post-Hiroshima era. Speaking of the West, Koestler wrote: “It seems obvious that a culture threatened by strontium clouds should yearn for the Cloud of Unknowing. Abdication of reason in favour of a spurious mysticism does not resolve the dilemma.” This was why I was particularly pleased that Breyten, who chaired the panel, began by reading a translation of a speech Ko Un had prepared for the event, since he could not actively participate owing to his lack of English. Skipping some of the initial paragraphs, Breyten starts with: “I have not come to South Africa to open wide my eyes, I have come here to get drunk,” unleashing riotous laughter as Ko Un raised his full glass with mirth in his eyes. Then his speech took a direction that soothed many of my misgivings:

It would be paradoxical to set up a view of “Nowhere” or “Utopia” when we are faced with the appalling scenes of bloodshed experienced in Palestine or South Africa as well as the current situation on the Korean peninsula, yet it is a hugely sincere and necessary wish. . . . In fact, we have to consider how useless abstract concepts such as “Nowhere” and brilliant intellectual expressions of it are, how remote a form of discourse they are in the extreme situations of such regions.

South Africa is a place where assumptions, which are brittle by nature, knock against sharp edges and fall apart.

Contrary to my initial expectations, this panel perhaps more than all the others eschewed the foreboding aura of the admittedly ambitious topics and truly attempted to do away with conceptualization, allowing panelists to voice the direct insights they had accrued through the course of their lives. As Osler, Ko Un, and Breyten spoke, I began to conceive that Zen could, in controlled doses, become a much-needed tool to defend intuition—which in the West has been under attack since the Enlightenment and has been all but eradicated from our lives—against the monopolistic claims of logic, which (who knew?) might in the end help mitigate our biologically ingrained jingoism and remind us that we are mortal leaves on an equally mortal tree. Regardless, there was no doubt in my mind that Petra Müller provided one of the highlights of the festival with the following, which she enunciated in her slow, elegant drawl:

I started thinking a great deal on the places of loneliness in our country, of the lair of isolation that we all have in us whether we want it or not, and it struck me very powerfully that to be descended from colonialists is a very strange business, because one of the things that you get to know about is that however many generations have passed—and as you all know we Afrikaners are extremely historically-conscious—there is always a part of you, way back somewhere, which does not belong. . . . I came to a conclusion. There are three “texts” that govern us: the family, the Bible, and the gun. They are not enough for us in Africa. . . . It seems to me that we have not lived long enough yet and that we shall have to live for a much longer time on this continent, before we who came here as colonialists—who had to deal with people whom we simply did not understand and also did not know, who had developed knowledges, intuitions, and psyches that knew more about this place than the people who had come in those “big wooden houses,” as the bushmen called the first ships they saw—can understand this place. I suggest that the god whom we got to know in the Old Testament is not always suited to that endeavor. Fortunately, there are many gods: some are penetrable, others completely impenetrable. The world of the Zen is a world we have to get used to. Once we get used to it, we see, strangely, that we have been surrounded by it from the beginning, but it took us over three centuries to get to the word “Zen,” which quite simply means “attention.”

Rightfully so, Petra’s speech drew thunderous applause and concluded the dialogic component of “Dancing in Other Words.” Yet in a sense, the dancing was still to come. Again at a loss to describe the elegance of Basson’s choreography and the quick footwork that Breyten and Ko Un displayed on the dance floor, here is Joachim Sartorius’s “The Palm Trees Tell Lies in Tunis,” in which the German poet evoked his youth in Tunis, where his father, also a diplomat, had once been stationed:

We don’t look that swell on the class photograph.

Alifa, star pupil with his ingenious mug, is blurred,

Monique, who I had a crush on, is wrapped in

scratchy silence. The photo’s so yellowed –

at head-level a horizontal irruption of light

(like the blond scraps of foam on the beach) –

that the viewer imagines he’s reading schoolchildren’s

cephalograms. In their midst is the teacher,

slender. Jusq’à l’os, I told her,

right down to the bone. She went red in the white TGM,

red as Monique’s nook in the boat off

the island of Zembra. Because no woman’s fairer

than the desire for a woman, my Arab friend

whispers. “The way she’s looking through her

legs. How tall she is!” and carves it into the wood

of the school-bench. Monique (father: Arab, mother:

French) walked home the same way as I did,

from the white station La Marsa to Gammarth,

beneath the furtive whispers of stocky, ancient palm-trees,

which still stand today, which don’t tell the truth:

That everything’s changed, each and everything.

*

The festival had come to an end, and although I had spent too short a time in so complex and stimulating a country, it seemed undeniable it was a place where assumptions, which are brittle by nature, knock against sharp edges and fall apart. Yet the constant hearing, reading, recitation—and one hopes retention—of poetry managed to soften those edges, slowing the mind down just enough to allow for at least a singling out of some of the crucial questions of our time, both in relation to the South African and the global context.

In the interests of full disclosure, I should perhaps mention that the absence of a major black African poet raised eyebrows among some in the audience, as well as a couple of the participating poets, who were surprised that three Afrikaners had been invited instead. While criticism of the sort is—and should be—welcomed, I do not agree. It seems rather natural for a festival held just outside Stellenbosch to feature Afrikaner poets, since that is where the word was first coined back in 1707. Furthermore, while I do not speak any Afrikaans and was therefore unable to understand Breyten, Petra, Antjie, and Marlene when they read out their work, I was pleased that they read in their mother tongue. At a time when Afrikaner culture is being marginalized—partly due to a myriad of understandable historical factors, partly due to the encroachment of a globalized broken English, this seemed to me particularly important. Still, where were the black writers? It may be controversial, but the fact remains that most of the country’s finest writers are still white. It is still largely true that readers versed in South African literature will have encountered the likes of Alan Paton, Nadine Gordimer, J. M. Coetzee, André Brink, as well as Antjie and Breyten of course—but not Adam Small, Wally Sarote, Mandla Langa, Achmat Dangor, Kopano Matlwa, or K. Sello Duiker—whom, truth be told, I only learned about because he’d won the Commonwealth Writer’s Prize for Best First Book. Why? Here’s what Lewis Nkosi said about the matter in 1991:

The answer may lie in all the things we don’t want to talk about: a poor and distorted literary education, a political criticism which favors mediocrity over quality, and exclusion from all those cultural and social amenities which fertilize the mind and promote confidence and control over literary skills.

Add to this the general nonchalance of publishers in London and New York, embodied by the publisher I’d spoken to before leaving London. Nkosi’s books, for instance, are all out of print there, save for Underground People, which is published by the niche imprint Ayebia Clarke. That the question of language and ethnicity should provoke such debate was of course foreseeable. Communication is clearly one of the greatest challenges in the new South Africa, and translation will—or should—play a large role in that. It remains to be seen whether the ANC government will step up to the challenge, or whether they will leave this to the mercy of private philanthropy, as has so often happened elsewhere.

Yet once all the wine had been drunk, all the poems read, the tables cleared and the dancing shoes laid to one side, I reflected on how impressed I had been by the audience’s vivid reactions to the words and ideas on display at the festival. People in South Africa definitely seemed to have a more sophisticated palate. They did not look awkwardly away or resent the spice. As far as I was able to gather, poetry draws a full house and a brief look at literary websites like bookslive.co.za, litnet.co.za, or slipnet.co.za—the last of which featured a series of articles prompted by the panel discussions—stand as a lively testament to that. In addition, the model adopted by “Dancing in Other Words” seemed to me a rather congenial one in that it allowed for deep immersion, which in turn facilitated some truly thought-provoking discussions rather than merely a focus on aesthetics or, rather, the entertainment factor. After all, people who attend literary festivals pay good money, so they demand at least a laugh or two. It has sadly become overwhelmingly apparent that the majority of publishers, writers, readers—in short, people—have somehow come to view politics and philosophy as pollutants of literary work. Yet to carry on down this road is innately dangerous. Tolstoy had warned of this back in 1897 in his essay “What Is Art?”: “It is this supplanting of the ideal of what is right by the ideal of what is beautiful, i.e. of what is pleasant, that is the consequence, and a terrible one, of the perversion of art in our society. It is fearful to think of what would befall humanity were such art to spread among the masses of the people. And it already begins to spread.” Of course, it’s far easier not to listen. It is easier to relegate, delegate even. Ignorance protects us from the weight of our responsibilities. Yet if being confronted with past and present injustices during those days in South Africa proved heavy on the soul, it was also strangely uplifting. After all, as Antoine de Saint-Exupéry once put it, it is from the injustices of today that we can create the justice of tomorrow, as no doubt Albie Sachs would agree. In time, it may very well be that South Africa—a country that has left an indelible mark on world history: imperialism, concentration camps, and of course apartheid were all coined here—will eventually go the way of every other liberal capitalist society, succumbing to a nihilism, that as Octavio Paz once remarked, doesn’t “seek the critical negation of established values” but instead enforces “a passive indifference to values.” It may very well do so, but for the moment it strikes me as one of the most inspiring places to be.

*

On the return flight to London, I attempted to concretize this vague vibe or impression—the quasi-indescribable zest that “you could smell in the air,” as Carolyn said to me during the course of that week—and turned back to Albie Sachs’s The Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter, leafing over to the epilogue, which I had left unread:

There is an historic openness and suppleness of texture [in South Africa] that makes life intensely interesting, and fills it with extraordinary choices. Part of the pleasure of living in this country today is its openness, the feeling that it can go any way, and that each one of us can still have an influence. Nothing is ordained, yet nothing is out of reach. For many, this freedom is disconcerting. They would rather live complaining under the firm authority of a powerful state, which, love it or hate it, would take all decisions for them, than slowly achieve security through the growth of a richly textured, multi-universed, and organically vibrant society. They fear the openness of freedom and resist taking responsibility for their lives.

On a final note, it occurs to me that of all the sights and sounds I absorbed during that week, I hadn’t yet figured out—or paid particular attention to—why the festival had been called “Dancing in Other Words.” Perhaps it was because Paul Valéry had once said that poetry is to prose as dancing is to walking, but of all the dancing metaphors I’d encountered over the past few weeks, I took a particular shine to these lines from Jack Gilbert’s “The Spirit and the Soul”:

The spirit dances, comes and goes. But the soul

is nailed to us like lentils and fatty bacon lodged

under the ribs. What lasted is what the soul ate.

The way a child knows the world by putting it

part by part into his mouth.

Cape Town

August 2013