“A World of Sharp Edges” A Week among Poets in the Western Cape (part 1)

After being invited by Breyten Breytenbach to attend the “Dancing in Other Words” festival in Stellenbosch, South Africa, this past May, André Naffis-Sahely sent us the following travelogue. Part 1 of 2 follows; the entire essay will eventually appear in a single post. A full gallery of photos from the festival can be seen here.

In Antal Szerb’s The Incurable, the eccentric millionaire Peter Rarely steps into the dining car of a train steaming through the Scottish Highlands and sees Tom Maclean, the writer, in a corner scribbling away. “I’m not disturbing you?” he asks, taking the empty seat opposite him. “You certainly are,” Tom replies, “Please stay and disturb me some more. It would be a real kindness. You see, at least while I’m talking to you, I won’t be working. Sir, the amount I have to do is intolerable. I’m fed up with myself, absolutely fed up. I’ve just been to Scotland for a bit of rest. I tell you—I was there for a month—in that time I translated a novel from the French, wrote two essays and a novella, eight sketches, six book reviews, ten longer articles and I’ve still got two radio talks waiting to be done.” “But why the devil do you work so hard?” Peter asks. “For a living, my dear sir, to make a living.” As Tom is so busy he doesn’t even have the time to read a book for its own sake, Peter decides to grant him a thousand pounds a year on condition he gives up writing entirely, a proposition Tom wholeheartedly accepts. A month goes by, during which Tom gives vent to his desires: he goes fishing, walking, learns foreign languages—and yet feels unnervingly restless, to the point that when he visits his sister’s family one afternoon and finds his nephew Freddy itching to go off to a football match, but unable to do so because he needs to finish an essay on Shakespeare and Milton, Tom writes the essay for him. Having failed to keep his end of the bargain, Tom calls on Peter to renege on their agreement: “I’m terribly sorry,” he says, “but I really have no choice in the matter.” “But haven’t you been happy without your writing?” Peter asks. “No, sir. It’s just no good. If you threw me in prison I’d write in blood on my underwear, like that Mr Kazinczy my Hungarian friend told me about. I wish you a good day.”

The “Mr Kazinczy” Tom refers to is Ferenc Kazinczy, one of the great Hungarian writers who, finding himself in irons after a failed Jacobin uprising, is said to have used his own blood when he ran out of ink. Rumor or not, it might as well have been true, for the point Szerb makes is that real writers rarely have a choice. Vague echoes of Szerb’s story echoed through my head as I listened to the panel conversations at the “Dancing in Other Words” festival, organized by Breyten Breytenbach, that took place in Stellenbosch, South Africa, on May 10–11, 2013. As the participants took their place on stage, I couldn’t avoid being reminded how high a price many of them had paid for their obsession to bear witness: Breyten Breytenbach spent almost two years in solitary confinement in Pretoria before being transferred to Poolsmoor in Cape Town for another five years; Albie Sachs lost his right arm and the sight of one eye in a car bomb placed by the South African secret services while working for the African National Congress (ANC) in Mozambique in 1988; Ko Un was imprisoned on four occasions in the 1970s and ’80s for his involvement in the South Korean pro-democracy movement; lecturing in New Zealand at the time of the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, Yang Lian and his wife, Yo Yo, opted for life in exile; after two years of documenting human rights abuses and dodging assassination attempts in El Salvador, Carolyn Forché was able to flee the country thanks to San Salvador’s archbishop, Óscar Romero, who was gunned down a week later during mass; even Tomaž Šalamun, who seems so unassuming in person, was threatened with a twelve-year prison sentence and held for a few days before being released—all because of a poem.

Of course, this is not to say these individuals are defined by their suffering. That would be a dangerous way to look at it: it’s often far too easy to sympathize with someone’s suffering than with the beliefs or ideas that led to that suffering in the first place, or even to miss the point entirely and ask asinine questions. As Albie Sachs says in his preface to The Soft Vengeance of a Freedom Fighter, “Was it worth it?–To this day they look without looking and ask without asking—was it worth it?” Instead, one should perhaps take a cue from Rumi, whom Breytenbach selected as one of the festival’s guardian spirits, and see “the wound as the place where the light enters you.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

*

On the evening of May 4, 2013, I went to Heathrow and boarded a flight for Cape Town. I had spent the previous six months living in the melancholy, mazelike city of Fez, Morocco’s ancient capital, translating the poetry of Abdellatif Laâbi, its greatest living poet. After which I had gone back to London, which I’d used as a base for the previous five years, chiefly in order to ply my trade as a literary translator and sign enough new projects to make a living. Soon after my return, I’d scheduled a meeting with a publisher with whom I’d once happily worked. We met for coffee one morning, and as I was trying to interest him in a novel by a Cameroonian writer, he cut me short halfway through my pitch: “To be absolutely honest with you,” he said, “I don’t much care for Africa, and neither do most people here. That’s just the way it is.” The next project didn’t fare any better: “Too political!” So I gave up, shook his hand, and left. Feeling the hunger to move, I got in touch with Breytenbach, who had commissioned me to translate Laâbi’s Le Règne de barbarie / The Rule of Barbarism for his Pirogue Poets Series, which aimed to issue the works of leading African poets in both their mother tongue and in English. Having heard that Breyten was assembling a gathering of poets, I decided to have a look at the polished but incredibly vague website. The names, or rather the books they recalled, were truly impressive: Ko Un from South Korea, Tomaž Šalamun from Slovenia, Yang Lian from China, Joachim Sartorius from Germany, and Carolyn Forché from the United States—with the South Africans Petra Müller, Marlene van Niekerk, and Antjie Krog rounding out the ensemble. All I could glean from the program was that they would meet for a week and “explore poetry’s age-old function as ‘the dreaming vein in the body of society.’” My first reaction was to giggle derisively. It all sounded incredibly pretentious. Then I checked myself. Was that what I really thought, or had close proximity to people like that publisher finally worked its nefarious charm? Coincidentally, I had just received Antjie Krog’s Skinned in the post a few days earlier. Picking it up from the stack, I opened it at the back and lingered over this stanza from “On My Behalf”:

Apathy neutralises the senses

as survival deploys its brutal forces one gets cut

off from others and becomes more and more

familiar with the complete inward-turning of death –

Had apathy made me giggle? There was one way to find out. I immediately sent Breyten a letter, hoping I would score a free ticket to one of the events and use what few coins I had left to buy an airline ticket. I couldn’t really afford it, but I would worry about that later. Unlike the publisher I had just spoken to—who was after all mirroring an all-too-prevalent reality—and after six months of splendid Moorish isolation in a Moroccan house whose blue tiles, as my partner put it, made it look like the bottom of a swimming pool, I was determined to spend some time with writers for whom talking back wasn’t so much a choice but a necessity. I waited impatiently for a reply. True to form, Breyten didn’t answer my missive, but an invitation from Marí Stimie, the festival’s project manager, materialized in my inbox a week later. Would I like to participate in this mysterious weeklong caravan? What a question! But there was a catch: I would have to take part in a master class in translation entitled “Lost in Translation, Found in Poetry,” the very sound of which made me squirm. When it came to theories about translation, I thought of them as the devil’s work, simply a means by which unscrupulous hacks could capitalize off the lecture circuit. Still, ever since I had met Breyten in Paris in 2008, I had realized the man had an infallible bullshit detector—one only needed to read his essays to see that—and so I agreed. “And you thought it was just going to be moonshine and drinking and chatting up the stones?” Breyten said in one of his later letters. Admittedly I had.

Settling into the twelve-hour flight, I began thumbing through Rian Malan’s new collection of essays, The Lion Sleeps Tonight, and stumbled on this passage:

Every inch of our [South African] soil is contested, every word in our histories likewise; our languages are mutually incomprehensible, our philosophies irreconcilable. My truths strike some South African writers as counter-revolutionary ravings. Theirs strike me as distortions calculated to appeal to gormless liberals in the outside world. Many South Africans can’t read any of us, so their truth is something else entirely. Atop all of this, we live in a country where mutually annihilating truths coexist entirely amicably. We are a light unto nations. We are an abject failure. We are progressing even as we hurtle backward. The blessing of living here is that every day presents you with material whose richness beggars the imagination of those who live in saner places. The curse is that you can never get it quite right, and if you come close, the results are often unpublishable.

I took this as a warning. The grandson of D. F. Malan, South Africa’s prime minister from 1948 to 1954 and the leading architect of apartheid, Rian started out as a tabloid crime reporter until the success of My Traitor’s Heart (1990) turned him from an exile draft-dodger into the new enfant terrible of South African letters, thanks to its uncompromisingly candid exploration of race relations—in fact, it was so uncompromisingly honest that Malan may well be remembered for the following line: “I loved blacks, and yet I was scared of them.” As the first free elections approached in 1994, Malan had been among those predicting “an orgy of ethnic butchery.” While not a few of his white compatriots shot off to Sydney and Dubai—“it’s like Joburg thirty years ago!”—Malan “bought a flak jacket” and “drew up a will”; ten years later, having realized the end was nowhere in sight, he penned a piece entitled “The Apocalypse That Wasn’t,” which ended on the following note: “The gift of 1994 was so huge that I choked on it and couldn’t say thank you. But I am not too proud to say it now.” Reading Malan was—I’m not sure he’s often been told this since everything about the man seems to indicate his only reason for getting out of bed in the morning is to ruffle feathers—reassuring. Here was a leading commentator calling it as he saw it and trying his best to keep an open mind—refreshing considering The Economist ushered in the new millennium by calling Africa “The Hopeless Continent.” Most articles about South Africa, and the African continent in general, I had ever read had that “sad I-expected-so-much tone” that Binyavanga Wainaina mocks in “How to Write about Africa.” Therefore, groundless speculation about the heart of darkness having become an industry in its own right—and not a small one at that—and despite the fact I had read a fair amount of South African literature, I made my peace with my inevitable idiocy and resolved to ask as many questions as a four-year-old on a sugar high.

*

When you tell South Africans living abroad you are going to Cape Town, you are likely to get two types of responses. First, their eyes will light up as they describe how impossibly beautiful it is; second, they will lower their tones and expertly inform you that you won’t be seeing the “real South Africa.” They might also tell you about the city’s knack for luring jaded Europeans looking for idyllic spots to detox and about the city’s bohemian feel and its wine-swilling hipsters, all of whom drive fast and talk slow—but that’s only if the conversation doesn’t drift to a relative or friend who was carjacked, mugged, raped, or killed. Flying over South Africa’s oldest city, your eyes skirt along the terrain’s rippled, rocky contours, past the miles and miles of beautiful beaches and finally settle on the cluster of mountains—Lion’s Head, Signal Hill, Table Mountain, and Devil’s Peak—that fence the central districts of Cape Town, whose regular grids recall the unforgiving Calvinism of its hard-nosed Dutch founders. With its very own Alcatraz, the infamous Robben Island where Nelson Mandela and other ANC leaders were imprisoned, jutting out of Table Bay, you’d be forgiven for thinking you’d landed in an African San Francisco, an arty, yippy student town with a modern CBD, large enough to still feel anonymous and yet cozy. Despite the lack of sleep, there was no doubt the first part of what I’d been told about the city was true: everything was ridiculously picturesque and paralyzingly beautiful.

I was met upon arrival by Faieez Alexander, the driver hired by organizers, and taken to a minibus, where Breyten was waiting with his white beard and beaming smile. Some of the other participants had also arrived that morning: Tomaž Šalamun and his wife, the painter Metka Krašovec, as well as Joachim Sartorius—who in his linen suit looked the sort of suave, cosmopolitan diplomat, which in fact he was, that you might picture as you read Lawrence Durrell’s Mountolive—and his wife Karin Graf, the German translator of Malcolm Lowry, V. S. Naipaul, and Joan Didion. Piling in, we set off on the thirty-odd kilometers from the airport northeast to the Spier wine farm where the festival was to be held. As we rolled along the N2, Faieez pointed out the miles of corrugated metal shacks of Khayelitsha, one of the fastest growing townships in South Africa and home to just under a hundred thousand families. I later learned that most of Khayelitsha’s inhabitants are blacks who left the countryside and migrated to the city, much like Azure, pronounced “Ah-zoo-ray,” the blue-eyed adolescent protagonist of one of the other novels I’d brought with me, K. Sello Duiker’s Thirteen Cents (2000), which with its brutal depiction of street life reminded me much of Mohamed Choukri’s For Bread Alone. Once Azure’s parents die, he hitchhikes to Cape Town and starts sleeping rough on the streets of the wealthy neighborhood of Sea Point, turning tricks to make a few bucks. Azure is that most frightening thing: an adult in the body of child; after all, as he repeatedly tells us, he is a man, as he is “almost thirteen.” The number thirteen keeps coming up. Azure is almost thirteen, he has thirteen cents in his pocket—and although that’s just about what Duiker tells us, I have a hunch the number thirteen also stands for the “Natives Land Act,” which was passed in 1913 and relegated blacks to 13 percent of the country’s land. “Land” is an inescapable word, concept, and reality everywhere in southern Africa, from Zimbabwe, where land redistribution has created a number of problems, to South Africa, where the lack thereof is equally problematic.

Once on Baden-Powell Road, the true glory of the Cape Winelands unfolded: having arrived right in the middle of the southern autumn, everything is reddish and golden and the air is brisk and slightly smoky. The Cape Winelands are like Napa Valley in California, the Bekaa in Lebanon, or Bordeaux in France: everything is packaged to seduce the well-heeled leisure-seeker: the hotels, set in green expanses, are both luxurious and homely, the food, served up by organic—sorry, “biodynamic”—eateries is twee, and of course wine flows so freely they might as well be pumping it directly into your veins. Although nowhere close to mining, South Africa’s chief source of export revenue, wine is big here: South Africa is the eighth largest producer in the world, and it’s also one of the oldest businesses. Starting in the late seventeenth century, the Dutch East India Company would hand out farm plots to its retired officials, who would then import slaves from Indonesia, East Africa, and India to work them. Wine farmers owned the largest number of slaves in the Cape throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A little under a year before we’d arrived, the town of De Doorns, one hundred kilometers northeast of Spier, in the heart of the Winelands, had been the setting of a five-month strike to raise the minimum wage from 69 Rand a day (£4.5/$7). Road blockades and a few fires later, the minimum wage was raised to 105 Rand (£7/$11) in February 2013. I am told Spier pays above the minimum wage, giving their staff 150 Rand (£10/$15). The difference may seem minimal, but it really isn’t. It was of some minuscule comfort to think that while I and my fellow guests would be wined and dined, our hosts did at least have some genuine convictions and ideals.

Cape Town may or may not be the real South Africa, but the Spier estate is not the real anywhere: it has a conference center, an art gallery, and hosts an annual arts festival, all in the midst of manicured lawns and little paths traversed by golf buggies transporting square-jawed preppies in sweater vests and their Stepford girlfriends to their spacious chalets. The estate is owned by Dick Enthoven, a dissident MP during the bleakest years of apartheid, who made his money in insurance and bought the farm in the early 1990s. The Enthovens have pumped a lot of cash into Spier: in a way, it seems to have less to do with wine than one might at first suppose. Having been to one or two such establishments before, I can’t recall them having had an amphitheater, a primary school, and a cheetah reserve on their grounds, or, for instance, giving out funds to Kayamandi, a township outside Stellenbosch, which we visited during our initial days there. Some might call the Enthovens philanthropic colonialists, others mavericks of the type that built model farms and villages in Victorian England. The fact remains that however much (or little) one may think they do, they raise an interesting question. As societies, we are continually told to be productive, to generate wealth, but never how that wealth can—or should be—used. I suspect antipathy toward the wealthy, the state, and institutions might be slightly less pronounced if more people of their economic class attempted to think outside the box.

While there are perfectly open-minded progressives who oppose tyranny and oppression walking the streets of Paris, London, and New York, they do not actually know what tyranny and oppression look, sound, and feel like, let alone the intricate ways in which they work.

We spent the first two days getting to know one another, beginning conversations that would be left off and picked up again throughout the course of the week and ultimately, it was hoped, inform the panel conversations. To be able to spend such a large amount of time together was certainly innovative. Most encounters at festivals usually amount to half-hour friendships, discussions end up being shoehorned into sound-bites, and everyone leaves worried about the schedules they’ve left behind. There are usually two sorts of literary festivals: the commercial kind where any half-brained performer of half-baked ideas is rolled out to recite their spiel for a fat honorarium—and then there are the odd, fairly small events funded by wealthy eccentrics, who are perhaps eccentric purely for the reason that they have decided to use their wealth tastefully. The latter of course are always more interesting, their less regimented approach being conducive to their becoming a laboratory of ideas, where thoughts—poems, even!—take shape on the hoof. Being aware that events of the latter variety are growing increasingly rarer in Britain or America allowed me to appreciate the time spent with the dancing poets all the more. It is one of the strangest features of free-market democracies that they grow progressively less interested in analyzing the world and looking beyond their functional plateau. In the so-called West, every day sees a major newspaper or periodical ask the question of whether culture is dying; at the same time, Hannah Arendt is a best-seller in Tehran, while the streets of Kolkata are positively overflowing with books, and dozens congregate around serious news-sheets pasted up on the walls to read and discuss them. Attend most literary festivals in Europe and North America and you will notice that while a shock-jock with a ghost-written memoir will ramble to sold-out crowds, an Angolan novelist will draw a turnout of six or seven pensioners. Thus, while there are perfectly open-minded progressives who oppose tyranny and oppression walking the streets of Paris, London, and New York, they do not actually know what tyranny and oppression look, sound, and feel like, let alone the intricate ways in which they work.

Many of these reflections have been fueled by a slim book I found in the tote bag the organizers had handed out to the participants, a gem entitled Pots and Poetry and Other Essays, by the Capetonian philosopher Martin Versfeld (1909–1995). In “Our Rapist Society,” perhaps one of the finest pieces in the book, Versfeld writes:

Democracy is a thoroughly ambivalent institution, requiring untiring attempts to fan the heavenly sparks still living among the ashes of self-interest. Notice the bearing of this image: it is the ashes that cradle the sparks. The tares and the wheat go together. This is the parable of the profound ambiguity of our situation.

*

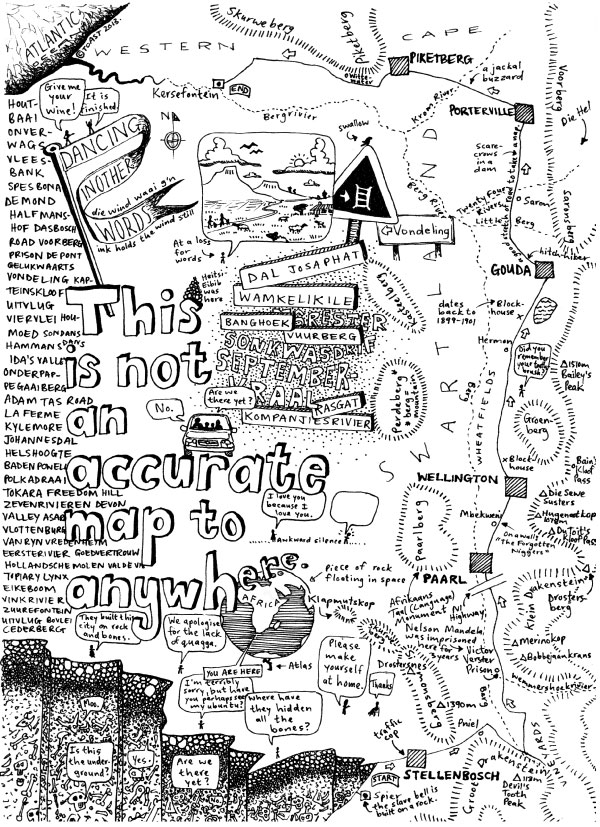

On the morning of May 7, we board the coach. Some of us are hung over, everyone wearing their sunshades to keep out the fierce sun. As we drive through the Boland, Toast Coetzer, a prominent young South African poet, acts as our informal tour guide, pointing out such sights as Victor Verster Prison, which has the distinction of being the last prison where Mandela was held before being released in February 1990.

As the afternoon draws on, we sit down to a lunch of exquisite Cape Malay food. Arriving late, I take the only seat left, opposite Ampie Coetzee, our host for the afternoon along with his wife, Anne-Ghrette. A fierce advocate of the Afrikaans language and literature, Ampie published many inflammatory works as head of Taurus in the 1970s and ’80s and taught at the University of the Western Cape—set up in 1959 as an institution for Coloureds, after the segregation of South African higher education—from 1987 to 2004. Ampie instantly appeals: his thick gray goatee, mischievous eyes, and wry, sardonic smile are winning. I linger on the eyes for a moment and remember stray lines from Breyten’s Intimate Stranger about writers being the “scattered or lost tribe of the world” and how when they meet, they “recognize one another by a look in the eyes as if squinting against the sun, and by the clumsy gestures of hands.” The lunch is animated. Ampie clearly possess a fearsome intellect and a biting sense of humor. “This man’s an absolute bullshitter, don’t trust anything he says,” he exclaims, slapping Breyten’s back in the way that you do only when you’ve known someone for a good handful of decades. “You can’t trust poets!” I had the feeling that, as with everything Ampie says, he was only being half-facetious. We were due to stop in Wellington for a reading at the Breytenbach Centre and then move on to Hopefield, a small settlement on the West Coast, deep in sandy-soiled farmland. Why Wellington? After years of unsuccessful attempts at managing small farms, Breyten’s father had moved his family to Wellington, where he opened a boardinghouse. (When it comes to family, look no further for one that encapsulates South Africa’s recent history: while Breyten was his country’s premier poet and cause célèbre before, during, and after his incarceration, his brother Jan was a colonel in the Special Forces and saw action in Namibia and Angola, while his other brother, Cloete, a reporter, photographed many of those conflicts.) Now converted into an arts center that often hosts readings and exhibitions by local artists, I was immediately struck by how, in one of those darkly humorous twists of fate, it was situated between a police station and a library. Just before the reading is due to start, Yang Lian and his wife, Yo Yo—a novelist whose works are for the most part untranslated—arrive, having missed their flight a few days earlier. With shoulder-length black hair, black jacket, and his perennial shades and grin, Yang looks like the baddest dude alive as he announces to the assembled crowd how happy he is to be there and apologizes for his “Yanglish” (which is sort of ridiculous since, despite stumbling over the occasional linguistic hurdle, Yang is one of the liveliest lecturers I know, having heard him speak on a number of occasions). After Breyten reads a few poems and gives a speech, the wine begins to flow—and while the others mingle and chat, I wander around the center’s sun-lit garden in the company of Bill Dodd, an old friend of Breyten’s and a fine poet, and drink from the fount of Marlene’s botanical knowledge as she points out various plants and flowers, occasionally translating poems pinned to the trees, some of which are hers.

Although Ampie was visibly pleased by the company and the event, it was obvious he was anxious about the direction his country had taken post-1994. After the festival was over, I pulled up an article he had written for A Moment magazine:

The gap between rich and poor has become wider than ever before in this country. Education suffered; and the greatest sufferers were black learners. One of the main reasons for this deterioration is the fact that instruction in the mother tongue has not been encouraged. The Constitution of South Africa states that there are 11 languages in the country, and that they all have equal rights. But this has never been made into a law. The situation has arisen that English is the favoured language; that English has become the national language. Practically all the previous Afrikaans universities will become English—at the expense of the other 10 African languages. The majority of the population of South Africa will be forced to become English-speaking. If language is understanding, if language is identity, if language is communication, there can be growth and one nation. But this will not be so in this country until people are educated in their mother tongue for at least the primary stage of education.

Complex as the new South Africa can be, the clichés of the rainbow nation that are routinely served up to outsiders by global—i.e., Western—media outlets make a concerted understanding of this country even more difficult. For instance: Is South Africa a better place than it was in 1994? The ANC says it is: all social and economic indicators are up, which is true, yet these are offset by rising costs of living and the widening wage gap. South Africa, we are told, is one of the most unequal societies on the planet, but that may also very well be because it is simply among the few heavily unequal societies to actually allow such surveys to be carried out. Like most other foreigners who have come here on brief sojourns, I could quote figures and statistics, but as Disraeli apparently put it, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics.” There is reason enough to believe that, like Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela, South Africa has also been stunted by its mineral wealth, which thanks to the easy income it provides, impedes creative thinking on the government’s part to push through necessary reforms and tackle critical problems. Moeletsi Mbeki, brother of Thabo, seems to think so. It also takes a split second to notice the public psyche is haunted by violence. Those who can afford to sleep behind barred windows and doors with “ARMED RESPONSE” signs prominently displayed on the walls, and with good reason.

For a glimpse at the post-1994 transition, there seems to me no finer book than Marlene van Niekerke’s Triomf, the first major novel written in Afrikaans after the end of apartheid and one of the most devilishly funny, heretically lyrical books I’ve read in some time.

When reality—or rather statistics, and the ability to process them objectively—fails, then we can thankfully make recourse to novels, which as Breyten once said, can “tell us truths that history cannot.” For a glimpse at the post-1994 transition, there seems to me no finer book than Marlene van Niekerke’s Triomf, the first major novel written in Afrikaans after the end of apartheid and one of the most devilishly funny, heretically lyrical books I’ve read in some time. Triomf—or Triumph—is a white-trash suburb of Johannesburg built over the ruins of Sophiatown, a black township. Enter the Benades, an incestuous, drunken family who, like Rian Malan, are ever on the ready to pack up and trek north like their Boer ancestors in case “the shit hits the fan” after the ANC takes power. Yet there is no north to go to. There is only the now, the haunting present:

In Triomf they know it’s actually just Ontdekkers that separates them. ’Cause across the road it’s Bosmont, and in Bosmont it crawls with nations.

Not that they have much trouble with them, here in Triomf. It’s only at the Spar in Thornton that the Hottentot children stand around and beg. Pop gives them sweeties sometimes when he takes Toby and Gerty to the little veld behind the Spar. But when the pianistic play with the dogs, Toby and Gerty don’t want to. All they want is to chase those big kaffirs who play soccer there. Young, wild kaffirs with strong, shiny legs and angry faces. And they play rough. Toby got his wind kicked right out one day when he tried to bite one of them on the leg. Pop says it’s ’cause Toby’s a white dog—although kaffirs are quite fond of dogs in general. Then Treppie says that may be the case, but it really depends how hungry the kaffir is. And then he starts telling that old story about Sophiatown’s dogs again.

When everything was flattened—it took almost three years—the dogs who’d been left behind started crying. They sat on heaps of rubble with their noses up in the air and they howled so loud you could hear them all the way to Mayfair.

Treppie says he saw some of the kaffirs come back one night with pangas, and then they killed those dogs of theirs. After a while, he says, you couldn’t tell any more who was crying, the kaffirs or their dogs. And then they took the dead dogs away in sacks.

Treppie says he’s sure they went and made stew with those dogs, with curry and tomato and onions to smother the taste. For eating with their pap. A little dog goes a long way, he says, and those kaffirs must’ve been pretty hungry there in their new place.

Some of the dogs died on their own, from hunger. Or maybe from longing for their kaffirs. And then their bodies just lay there, puffing up and going soft again, until the flesh rotted and fell right off the bones. Then, later, even the bones got scattered.

Even now Lambert finds loose dog bones when he digs.

Treppie says the ghosts of those dogs are all over Triomf.

*

Leaving Wellington behind, the coach rolls smoothly along the quasi-deserted roads and the sky begins to fill with broody clouds. All of a sudden, the Afrikaners on board start to whisper conspiratorially. Before we know it, we make a sharp right and park the behemoth of a coach in someone’s backyard. A bespectacled man busily washing the dishes peers out confused from his kitchen window. As the Afrikaners descend, a mountain of a man emerges from his back door, looking as though he’d just woken up or come off a three-day bender. All the Afrikaners lit up with joy, while everyone else looked on bemused. As no one explained much to us, we didn’t know why we should be so excited. Luckily, Albert Du Plessis and Carel de Beer, the incredibly friendly and knowledgeable filmmakers that Spier had hired to film “Dancing in Other Words”—and whom I would often oblige for “insider” information throughout the trip—provided the context. The man in question was Gert Vlok Nel, a poet and one of those untranslatable chansonniers in the style of Brassens, De André, or Dylan who sings about white working-class life and who is both an outsider figure and yet praised as an outstanding talent by pretty much anyone in the know worth listening to in South Africa. After a friendly chat, it’s time to continue on to Kersefontein, but not before Gert, egged on by the Afrikaners, grabs the mike and orates a poem. The words flow incredibly smoothly, and I fill with rage at being unable to understand it. This would happen often throughout the trip, but that time it truly stung.

Just before sunset, we arrive at Kersefontein—or “fountain of wild cherries”—and as the coach sneaks past the gatepost, marked 1770, history is already inescapable. Settled by Martin Melck, the farm is still in the family’s hands after eight generations and is currently managed by Julian, who has also opened his doors to tourists, offering up his unique abode to those seeking a rustic retreat. The manor house, in the old Cape Dutch style, with its period furniture, stately dining hall, and musty, stale tobacco smell—or was it wax?—is impressive. Julian is an energetic host, and his presence makes itself felt everywhere. He hands me his business card:

JULIAN MELCK

FARMER – PIG-KILLER – AVIATOR

Julian studied law at Stellenbosch University, worked briefly in Windhoek, and then took over the farm once his father retired. In his sixties, he looks twenty years younger. The punishing routine he keeps, sleeping roughly four hours a night, has clearly worked wonders.

Save for Neo Muyanga’s crash course in various traditions of South African music, which the Sowetan-born musician delighted us with one morning, the two-day stay at Julian’s farm was mostly an occasion to drink—in a bar adorned with Julian’s flying memorabilia—relax, and continue our conversations. The evenings before supper would see us enjoying the starry sky, sitting on the steps at the front of the house; on one occasion, Albert and Carel regaled me with an account of the Bantu expansion, one of the greatest mass migrations in history, when Bantu-speaking peoples moved from western Africa toward the Congo and southern Africa, drastically altering the face of the continent. While they talked, I couldn’t help but be struck by the connectedness the Afrikaners seemed to have to their land. This was further impressed on me by our visit to a small graveyard that housed the remains of centuries of Julian’s forebears. With ancestors from several different ethnicities across two continents, it was difficult for me to even fathom the sort of rootedness that this graveyard represented, but it was certainly strange to weigh the Melck family’s thousands of hectares against the repercussions that the Natives Land Act has had on South Africa’s blacks, which effectively tossed them out of their farms and turned them into a supply of cheap labor—if not for wine and fruit concerns, then for the mines. Julian is a true gentleman and by far one of the warmest people I met during the trip. Yet his estate could not help but stand out as an emblem of the pernicious legacy of colonialism and apartheid, which still presents untold problems for the country’s future.

On our second and final afternoon at Kersefontein, we assembled in the breakfast room to listen to Petra’s gripping lecture on the history of Khoisan people, the original inhabitants of this corner of South Africa, who could trace their genetic lineage back one hundred thousand years. A wonderfully descriptive storyteller—our griot, we all concurred—when Petra mentioned the thin, emaciated aspect of the Khoisan she’d encountered, it reminded me of a couple of lines from “Reading Disgrace,” the poem she’d composed for the festival: “Emaciation is a theme which never lets one alone. / When the ribs become visible, even words achieve their honesty.” The younger participants of the festival then read some of their work aloud; of particular note was a letter Dominique had written to her parents to explain her thoughts behind the writing of her novel, False River:

What is writing if not an exercise in recuperating memory? It is stopping to listen—of consciously being alive and attentive. Memory is the mentor of imagination, as stars are its vectors. The discipline of writing is also a great gift, a freedom—by writing one is gradually relieved of the sense of uniqueness of self. It is in many ways a liberating shuffle in the direction of humility.

Although the Afrikaner writers I was acquainted with—like Breytenbach and André Brink—had written in Afrikaans partly also out of a political desire to demonstrate that it was not exclusively the language of apartheid, often then translating their own works into English, younger writers like Dominique, who wrote False River in English and then translated it into Afrikaans, appeared to be finding new approaches to their language.

As we set off the next morning, I sat staring out of the window, contemplating the Khoisan, how different the stars looked in the southern hemisphere and the song Ko Un had sung for us on our last night. Weeks following my return to London, I received this poem in the post, “Ko Un Sees Stars,” which Toast had composed in the wake of our stay—and which I believe summed up that time perfectly:

the Korean poet Ko Un

is outside on the lawn

in the night and recalls

Tibet

and the Himalayas

the closeness of those stars

which he wrote many poems about

says his wife

translating his thoughts and words and life

but now

here on the banks of the Berg River

she says he says

he feels

less

less in comparison with all these stars

less

and then he sings “Arirang”

their folk song of lovers’

longing across adversity and stars

as if this is the first song he ever learnt

which he probably did

and the last one he will ever sing

which he probably will

and the night sky above us

intensifies and blows

a billowing leaking Bedouin tent

of white coals and deep space cities

light years and sunny porches

as we bow down to the lawn and listen

to Ko Un

the mighty

Ko Un

Cape Town

August 2013