Native Nonfiction in the Classroom and Beyond

In spring 2020 I had the opportunity to teach two Native literature classes at two different community colleges in Coast Salish territory. I was excited about including readings that I admired, that would lead to engaging discussions, and that featured writers from the region. Many of the writers on my syllabus, like Terese Maihot, Ernestine Hayes, and Deborah Miranda, have written excellent and well-regarded books, while others—like Sasha LaPointe and Ruby Hansen Murray—are working on books that I greatly anticipate.

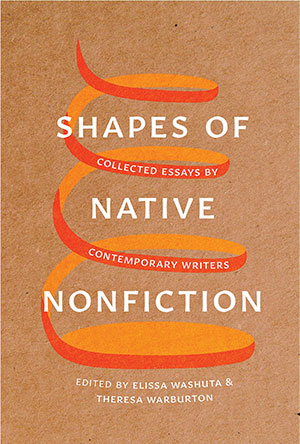

For both of my classes, one that was primarily non-Native and the other that included all Native students, I chose selections from Shapes of Native Nonfiction, edited by Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton (University of Washington Press, 2019). As noted in Nichole L. Reber’s review of this anthology, Stephen Graham Jones’s essay, “Letter to a Just-Starting-out Indian Writer—and Maybe to Myself,” along with the other selections, delves directly and indirectly into expectations about Native literature (WLT, Winter 2020, 100). According to Reber, the anthology doesn’t feature “instantly recognizable literary rock star names.” This key feature made me want to include it on my syllabi and personal reading list because too often non-Natives only read or are aware of a limited selection of Native writers. This is a particularly exciting time in Native literature, but oftentimes Native writers do not get the attention they deserve.

For both of my classes, one that was primarily non-Native and the other that included all Native students, I chose selections from Shapes of Native Nonfiction, edited by Elissa Washuta and Theresa Warburton (University of Washington Press, 2019). As noted in Nichole L. Reber’s review of this anthology, Stephen Graham Jones’s essay, “Letter to a Just-Starting-out Indian Writer—and Maybe to Myself,” along with the other selections, delves directly and indirectly into expectations about Native literature (WLT, Winter 2020, 100). According to Reber, the anthology doesn’t feature “instantly recognizable literary rock star names.” This key feature made me want to include it on my syllabi and personal reading list because too often non-Natives only read or are aware of a limited selection of Native writers. This is a particularly exciting time in Native literature, but oftentimes Native writers do not get the attention they deserve.

Because this anthology features a variety of writers, it is able to showcase a diversity of voices. Some of the writing is humorous or animated, some is poetic, and yes, some of the essays may have a pointed or much-needed angry quality. But I would never describe, as Reber does, Tiffany Midge’s writing as “fiery,” with “aggressive diction [that] could be used in warfare.” I read this critique as tone-policing and too close to the damaging stereotype of Natives as savages. In fact, I had to go back and read Midge’s two essays and found both of them used a level tone. If I had found that they were written in an angry tone, I would have thought it was an appropriate tone for essays about fertility or colonization.

As a Native writer, one of my pet peeves is when literature written by Native writers is evaluated only for what it can reveal about Native cultures and not the craft the writers are employing. In Jones’s essay, he advises, “Insist that your work be dealt with as art, not as an entry point to culture.” This is why I found Washuta’s and Warburton’s analogy of basketry as a means to enter into a discussion and framing of the anthology so important. The framing of basketry and the formation or practice of basketry direct readers in a culturally relevant manner to the various craft components and techniques of the essays.

The framing of basketry and the formation or practice of basketry direct readers in a culturally relevant manner to the various craft components and techniques of the essays.

The nuances related to the focus and organization of this anthology can be lost on some because its editors did not use basketry as a simple metaphor. In a Longreads interview with the editors, Warburton writes: “What we’re trying to do is emphasize, instead, the fact that the authors practice craft not only to tell a story but also to evidence the shape of the multiple worlds in which that story interacts.” The editors’ use of basketry and weaving relates to both the practice of creating and the three-dimensional nature of baskets. I regret that I didn’t have more time to discuss this structural aspect of the anthology with my classes, but I will continue to reflect upon these concepts as I spend more time with the anthology.

In the penultimate sentence of her review, Reber writes: “Academic literary qualities such as experimental essay types and the abundant racial/gender subject matter indicative of the early twenty-first-century zeitgeist make this a likely tome for the classroom.” While the topics and experimental structure of some of the essays do make for vibrant conversations, they are not just useful in the classroom. In addition, it didn’t occur to me that the anthology contained essays with an “abundant racial/gender subject matter.” Instead, I viewed the essays as being about timeless topics that are important to Native writers and communities and therefore worthy of being explored in many shapes and forms.

Northwest Indian College