Ideas of Order

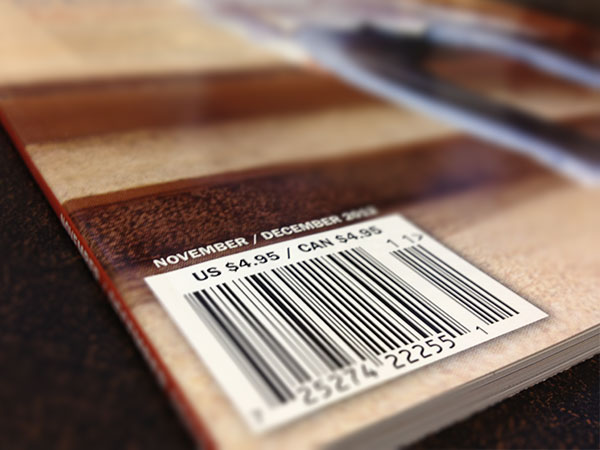

Reading the portfolio of law-inspired literature in WLT's November/December 2012 issue, I found myself lingering over not only the contents, but that little string of characters on the cover that tells the price. That tiny datum loitering down by the bar code, hidden in plain sight, tells a story about the law, just like the narratives in the portfolio. It even talks back to them.

The story it tells is that, sometimes, the promise of the law is kept. It was kept, for instance, when you bought your issue of WLT. If you’re the rare soul who still ventures into a bookstore to buy a magazine, you plunked down your legal tender and walked out with what the law had just made your rightful property. You didn’t have to smuggle the issue in your coat or knock anybody upside the head with a brickbat. And nobody will be cracking you over the skull for your copy, at least not with impunity.

The price on the cover is an emblem of the security and orderliness that the law should and, if circumstances are right, can impart. Security and order aren’t everything, of course, but they’re something. They’re conditions for human flourishing: necessary, though not sufficient. Justice Cardozo described the due process rights preserved by the U.S. Constitution as stemming from a “concept of ordered liberty.” It’s an apt phrase—“order” being the thing that makes “liberty” survivable. All this might be obvious, but it’s worth stating before turning to the portfolio’s image of how law works in the world.

And what is that image? Well, the first thing to say about it is that it is a negative one. That might sound harsher than I mean, so let me elaborate (warning: spoilers).

I mean, first, the obvious sense of negativity: derogation. The portfolio portrays the law as a tool for entrenching the powerful and oppressing the powerless (as in Francisco X. Alarcón’s “Self-Questions for Possible Suspects under Section 2(B) of Arizona SB 1070” or Deena Padayachee’s online story, “Prisoners of the Past”). Or else the law is an obstacle that true justice must skirt (as in Martín Espada’s “Thieves of Light”). Sometimes, the law is nothing more than the idiots tasked with upholding it (as in Juan Pablo Villalobos’s “Immoral Acts” or Espada’s “Offerings to an Ulcerated God”).

Representative of the portfolio’s bleak view of the law is Mahmoud Saeed’s dire “Lizard’s Colony.” In that story, which WLT nominated for a Pushcart Prize, the law is not much more than a cynical fig leaf for atrocities. An Iraqi mother agrees to act as an interpreter at a U.S. military prison in exchange for an astronomical salary that will pay for medical care her daughter needs. Arriving on base, she’s immediately raped. Not only is justice for the crime denied, but her supervising officer (in a scene that makes a grotesque of contract law) hints heavily that her high salary compensates for her troubles. By story’s end, she finds herself participating in the death-by-interrogation of a detainee who expires with blood seeping from his electrocuted penis. Then she is made to help with the cover-up.

Do you see what I mean by a “negative account”?

I don’t deny that these or similar nightmares happen in real life, that they happen nearly always to the disempowered, or that they are atrocities. I also admit, readily, that people who look like me and share my privilege do too much of the perpetrating. Indeed, my appreciation for the order the law can provide is surely formed by a life spent living and working—in the law—in the United States. The portfolio reminds me that the law too often is a vehicle for cruelty and stupidity.

The price on the cover, though, reminds me that it’s not only that. Which brings me to the second sense of “negative”—the photographic sense. The law-and-lit portfolio presented an image of law, but a negative one, defined by what it isn’t. It showed law gone wrong, law disconnected from justice, law that is nothing more than authority. The high quality of each piece is striking, and the opening essay is a good orientation guide. What I missed in the portfolio was something in addition to these pieces: a vision of what law might be, or at least a deeper exploration of its ambiguities.

They’re not unknown in literature. Take the genre of the western, with its “outlaws” and “lawmen.” If we accept movies into literature’s big tent, unfashionable, brilliant old films like Twelve Angry Men or the lesser-known, more majestic A Man for All Seasons dramatize not just how the law can fail, but how it might not. Now in theaters, the flawed but worthwhile Lincoln is not so much the story of its namesake as of the passage of a good law, the Thirteenth Amendment. It’s possible to tell the kind of stories I’m thinking of.

And they ought to be told. Richard Rorty once wrote of patriotism that, just as self-esteem is a necessary condition for improvement in individuals, national pride is for countries. Isn’t the same true for the law? To spur improvements in the law, shouldn’t writers, in addition to shining a light on injustice, shine it on how justice might manifest?

One story in the portfolio begins to wrestle with that task. In “Anyone Have Any Idea What Jesus Wrote Here?” Sophie Hardach imagines an expatriate author in Peru who sees a pirated, sentimentalized version of her novel go blockbuster and calls the cops on the poor bookstall vendors. The story appears to employ Hardach’s own ambivalence toward the copyright laws which enable her to profit from her writing, yet make her work too expensive for the poor—which, ironically, leads to piracy.

More of Hardach’s ambivalence might have made the other narratives even stronger than they were. As it stands, the dominant note was one of outrage, extracted from a hard kernel of moral certainty. Like a dish with too much chili, it was hard to taste much else.

WLT’s law-and-lit portfolio reminded me, in fact, of another themed issue I read recently: Rattle, the Los Angeles poetry journal, featured “law-enforcement poetry”—poems by cops. The police imagination is a fascinating thing. Law-breakers are, patently and patly, “turds.” Several poems express dismay that one’s fellow officers might not be bone-deep “Guardians of the Good,” as one title puts it. Those earnest poems remind me of the WLT law-and-lit portfolio because there, too, the law took on a singular, monolithic, and, as much as it pains me to say it, oversimplified character. Only, in the officers’ poems, law and order were too exalted.

Law and literature are natural companions, since both answer the question How should we live together? The portfolio said, clearly and artfully, “not like this.” I wish it had also said like what.

Oakland