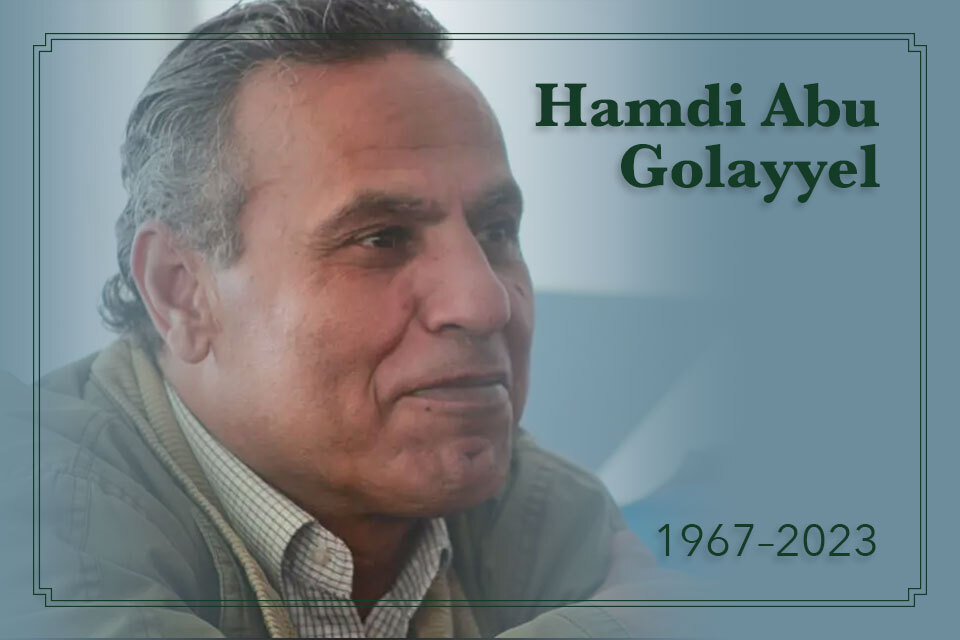

Hamdi Abu Golayyel: A Gifted Storyteller with an Eye on Rogues and Tall Tales

Hamdi Abu Golayyel (b. 1967) was a gifted storyteller who fused Egyptian oral storytelling, myth, and folklore to tell the tales of marginalized and working-class communities in Egypt. He died on June 11, 2023. He was only fifty-six. I did not know him personally but reviewed the translation of his recent novel, The Men Who Swallowed the Sun, for the magazine Banipal. In one of those ironic twists of fate, I had asked a journalist friend for his phone number because I wanted to meet him. I received the number, but months passed and I didn’t follow up on the impulse—sudden death is a poignant reminder of the precariousness of our existence on this earth. Apparently, Abu Golayyel was as colorful in real life as the characters in his work. He was often seen in a 1950s automobile, driving between the Pyramids and downtown Cairo with his deceased pal/poet, Osamma El-Danasoari. The spirit of Abu Golayyel’s work has been artfully rendered into English from the Arabic by three distinguished translators: The Men Who Swallowed the Sun, by the late Humphrey Davies (2022); A Dog with No Tail, by Robin Mogers (2009); and Thieves in Retirement, by Marilyn Booth (2006).

Hamdi Abu Golayyel (b. 1967) was a gifted storyteller who fused Egyptian oral storytelling, myth, and folklore to tell the tales of marginalized and working-class communities in Egypt. He died on June 11, 2023. He was only fifty-six. I did not know him personally but reviewed the translation of his recent novel, The Men Who Swallowed the Sun, for the magazine Banipal. In one of those ironic twists of fate, I had asked a journalist friend for his phone number because I wanted to meet him. I received the number, but months passed and I didn’t follow up on the impulse—sudden death is a poignant reminder of the precariousness of our existence on this earth. Apparently, Abu Golayyel was as colorful in real life as the characters in his work. He was often seen in a 1950s automobile, driving between the Pyramids and downtown Cairo with his deceased pal/poet, Osamma El-Danasoari. The spirit of Abu Golayyel’s work has been artfully rendered into English from the Arabic by three distinguished translators: The Men Who Swallowed the Sun, by the late Humphrey Davies (2022); A Dog with No Tail, by Robin Mogers (2009); and Thieves in Retirement, by Marilyn Booth (2006).

Recognized in Egypt for his talent, he was the recipient of four literary awards: Ja’izat al-majmu’a al-qisasiyya (Award for a Short Story Collection), Ministry of Culture, Egypt, 1997; Ja’izat al-qissa (Award for Fictional Narrative: Short Story), Akhbar al-yawm, Cairo, 1999; Ja’izat al-ibda’ al-*Šñarabi (Arabic Creative Writing Award), United Arab Emirates, 2000; and the Naguib Mahfouz Prize for Fiction, the American University in Cairo, 2008.

Abu Golayyel was one of the few voices from a Bedouin background on the contemporary literary scene.

Abu Golayyel was one of the few voices from a Bedouin background on the contemporary literary scene. (Another well-known writer with a conservative Bedouin background is Miral Al-Tahawy, who has been recognized for her novels, which focus on Bedouin women.) Yet in all three of his translated works, he suggests that being a Bedouin man is not a cakewalk, either, bound by the rigid expectations and codes of a traditional community with a long history. The narrator in his short-story collection, A Dog with No Tail, tells people in the village that he was working as an airplane pilot in Cairo rather than admit he was working as a day laborer. And then there is “Baffo,” the likeable, self-deprecating scoundrel in his novel The Men Who Swallowed the Sun, a Bedouin who believes he must “amass millions” in Italy to satisfy his family and a potential bride. The narrator emphasizes the point by saying that his mother started treating him like a man of the family when he was only five years old! He works in Libya as a construction worker, bootlegger, cook, auto repairman, and concrete-block maker before his dangerous crossing on a tiny boat across the Mediterranean. Despite his attempts at finding honest work in Italy, he ends up dealing drugs and eventually escaping back to Egypt, on the run from a mafioso boss. Since there are few opportunities in his tiny village, the narrator in both novels and the story collection seeks his fortune elsewhere: Cairo or Europe. In his novel Thieves in Retirement, the narrator explains how the Ottoman viceroy Mohamed Ali Pasha distributed lands to his Bedouin ancestors in order to placate them in the nineteenth century. They left their deserts for a new adopted land, near Fayoum. Even though they had been granted land, they retained their nomadic identity with “fierce pride,” turning their nose up at farming. He does not pull any punches when he says about his family: “they remained loyal to the principle that planting and tending the land they’d been granted was beneath their dignity, and they were delighted to barter it away for the most worthless trifle.”

Besides the wild exaggeration that is characteristic of an oral storyteller, Abu Golayyel’s work pivots around flamboyant characters on the fringe.

Besides the wild exaggeration that is characteristic of an oral storyteller, Abu Golayyel’s work pivots around flamboyant characters on the fringe—drug dealers, thieves, prostitutes, hustlers, day laborers, and migrants. In A Dog with No Tail, the Bedouin aspiring novelist who supports himself by doing construction work introduces us to the invisible day laborers of Cairo, a motley crew. One of the narrator’s pals, nicknamed the “Doctor” since he once worked in a pharmacy, is a quirky, pragmatic character who conjures a way of getting out of daytime work in “Dreams.” Instead of hauling sacks of sand up to a building, he guards trucks at night. But then he figures out a way to reward stray dogs with bones so that he can sleep through the night. Later in “A Film,” the “Doctor” works as an assistant to the porter at an actress’s building and personally benefits from the informal prostitution ring in the garage downstairs. The narrator comments: “His philosophy is first: ‘Morning sunshine! You mind your business and I’ll mind mine.’ Then, it was ‘that’s one thing and this is quite another.’ He would finish with a prostitute so he could go to pray in the mosque.” Abu Golayyel was not afraid to take digs at religious hypocrisy.

Abu Golayyel also zeroed in on the hypocrisy and falseness of political rhetoric. In his novel Thieves in Retirement, the landlord, retired from the Helwan silk factory, remembers the visit of The Leader, ostensibly the Egyptian president Jamal Abdul Nasser, who congratulates the workers for sleeping at the factory because he believes they are working double shifts! When Abdel Halim points out that they have no place to live, The Leader “waved toward a vacant stretch that happened to be within eyesight,” as if he were waving a magic wand. Yet the narrator observes that Nasser’s “Newtown” is “part village and part unplanned city fringe, destination of squatters and incomers.” Likewise, in the opening of The Men Swallowed by the Sun, the narrator begins with the outlandish legend that the Great Leader (i.e., the ex-Libyan dictator, Muammar Qaddafi) is related to the Egyptian Bedouins from Fayoum. He then goes on to recount the various legends about the leader: “One story says he was a Jew, his mother, a Jewess from Tel Aviv. Another claims he was of French extraction, his father a pilot who fell from the skies of the Second World War onto the tent of a bunch of Libyan Bedouin roaming around in the desert, and then he married their daughter, who bore him the Leader.” The myths are just as bizarre as “real history.” Or perhaps history and political rhetoric are pure fantasy.

Abu Golayyel really hit his stride with the novel The Men Who Swallowed the Sun.

While both A Dog with No Tail and Thieves in Retirement are carefully crafted with lean prose, one feels that Abu Golayyel really hit his stride with the novel The Men Who Swallowed the Sun, which was awarded the Banipal Prize for Arabic Translation in 2022. The swashbuckling characters are made vivid by Humphrey Davies’s vernacular translation. The picaresque novel is spacious enough to house the hilarious digressions, philosophical musings, biting satire, and character sketches in a manner that is entertaining and satisfying at once for the reader: a rambunctious gallop through Egypt, Libya, and Italy, with plenty of adventure. Maybe a little reminiscent of Mark Twain’s semi-autobiographical novel Roughing It, set in the American West (1861–67), where the narrator goes west in search of gold, while the migrants in The Men Who Swallowed the Sun are searching for gold in modern-day southern Europe.

Dar El-Sharouq, an Egyptian publisher, has posthumously issued Abu Golayyel’s last novel, Dek Omi (The rooster of my mother). The title is a euphemism for a curse in Arabic: “To hell with the religion of my mother.” The recent event was attended by critics, literary figures and his family members.

We do have the pleasure of reading one last tale from what seemed to be Abu Golayyel’s bottomless bag of stories.

Cairo