On When They Asked Me about Borges’s Sexuality

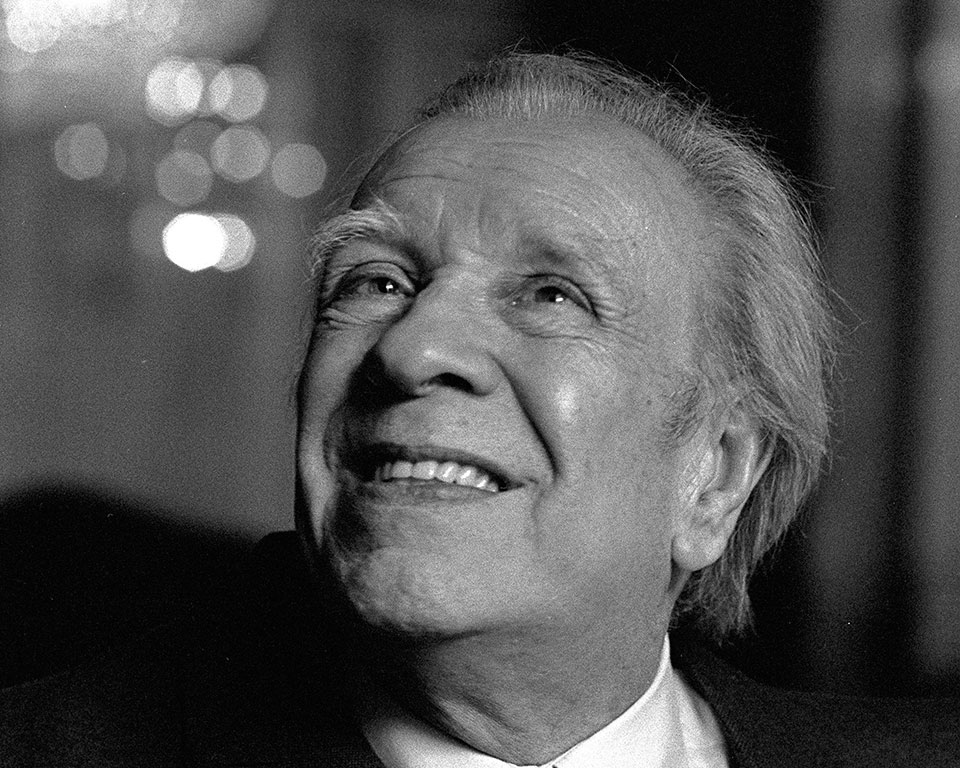

Because June 14 marked the thirtieth anniversary of the death of Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986), I received a couple of calls, asking if I would be interested in answering some questions. Part of what I said would be published.

I must confess that it made me very happy. As is customary on the anniversaries of famous people, there will be a lot of statements in the media about this very topic, but Borges has always been one of my favorite authors: one of the very few who really, for good and bad and everything else, have mattered to me and changed my life. What’s more, I continue to believe him to be the creator of many breathtaking fictions, a model for writing and reading, a literary innovator long before the word innovation became trivial, . . . and an extremely dangerous teacher, like all truly great writers: the creator of a work (precisely) so captivating, innovative, and open to imitation who is able to completely subjugate the creative capacity of whomever tries to copy it in a naïve way, without leaving room for anything else. The thousands of Borges admirers who never managed to go beyond writing fan fictions based on the work of their idol published their work, for the most part, before the appearance of the Internet and the acceptance of fanfic as a valid form of nonprofessional writing. But they existed, and do exist, and can be found out there, in archives and in old books.

And, of course, there are those who manage to keep Borges from consuming them, although they are few, and instead incorporate him in new texts (very Borgesianly) that are not embarrassed to sound like a tribute, intertextual reference, appropriation.

I said some of this yesterday, but it wasn’t easy: in one interview, the first question I was asked was about Borges’s sexuality. Infrequent, they said, unusual, like in his stories.

The first thing that came to mind was an article on Hans Christian Andersen, published in his own centenary in 2005, which doesn’t say a word about Andersen’s oeuvre and instead is dedicated to providing a pathetic portrait of the repressed homosexual, the vindictive upstart, the complicated and ugly man, like the duckling, which was Andersen. I’m intentionally omitting who wrote it and where it can be found.

Eleven years ago, that text outraged me because it was dishonest: sensational and sordid. Now it seems ahead of its time. Today it would be one among many that appear daily about any moderately famous person: another sign of how morbid and superficial our cultural references are, especially online.

Next, it occurred to me that I could answer the question about the sex life of Borges with platitudes: Borges scarcely refers to sex in his work and has scarcely any female characters, which “could be” a sign of shortcomings in his character, of machismo, asexuality, fear of women; his first marriage “could be considered” a failure and the second as a mere formality, made official shortly before his death just so he could leave his estate to Maria Kodama, his lover/scribe/assistant/caregiver; “without a doubt” the contempt he felt for psychoanalysis was because it made him feel exposed, and so on. I have read or heard all these phrases, with all their imaginable malice, often together and separately. Although they all seem terrible to me, it is now acceptable to speak ill in this way under the pretext of “demystifying” whomever the target may be. I have also noticed that much of the news about Borges in recent years has been, in one way or another, about scandals and disputes.

So what did I do? I chose to remember that Borges is not a writer of the era of Facebook and autofiction; that it is not true that he hides in his texts, speaks little about himself (in fact, the opposite is true: how often in his work does his double appear, the character called Borges?); he simply does not do it the way in which we are accustomed today; that, like his friend Alfonso Reyes, Borges learned the classical notion of decorum, which is a set of rules of style when writing and also a certain principle of discretion, an obligation not to say absolutely everything that is very likely inconceivable to many people today.

I also said something about Borges’s love life, which is present in several places in his work, just like his reticence, yes, to go beyond “a certain point” (in the story “The Other,” for example, various critics have found a subtle reference to a brothel and a prostitute located almost in a blank space, between two French names that are almost identical).

And then I talked a little about what interests me most about Borges: his imagination, his problematic but in the end (or in his best moments) rebellious relationship with power and violence, what he still has to say about reading, tradition, the way in which we create (or he created for us) images of the world, models, ideologies.

Of course, there will come a time when what Borges wrote no longer means anything. It will happen to him just as it has, and will, to everyone else. The truths that literature uncovers are always provisional and depend—at best—on the words they are composed of: that is, if they aren’t previously erased by changes in human cultures, when the languages of those cultures, those of living people, begin to move away from them, their meanings begin to grow dark, and that darkening is irreversible.

But the truths that can be glimpsed in Borges’s work are not derived from the morbid attractions that matter so much to us now. They are elsewhere, and their time to disappear has not arrived, even as they seem distant from those things that obsess us.

Since another common practice today is the out-of-context quote, misinterpreted without the slightest remorse, allow me to end with one: “The world, unfortunately, is real,” Borges wrote in one of his great essays, which could be read as an acknowledgment or a surrender.

And yet, immediately after, Borges wrote something else, which can be read either as a response or a challenge: “I, unfortunately, am Borges.”

Translation from the Spanish

By George Henson