A Sad Rush of Wings: A Tribute to Sergio Pitol

In the days before his death, Sergio Pitol had been much on my mind: the sordid stories of neglect splashed across Mexico’s leading newspapers; court battles for his guardianship; accusations of theft and embezzlement; all this while the Maestro lay bedridden, a prisoner in a neurological dungeon, dying.

As I write this, I remember Pitol, the boy, who was also bedridden for long periods of time, where books were his only solace, among others, the adventures of Jules Verne, from whom he acquired the love of travel, which would eventually take him around the world, away from his native Mexico for twenty-eight years.

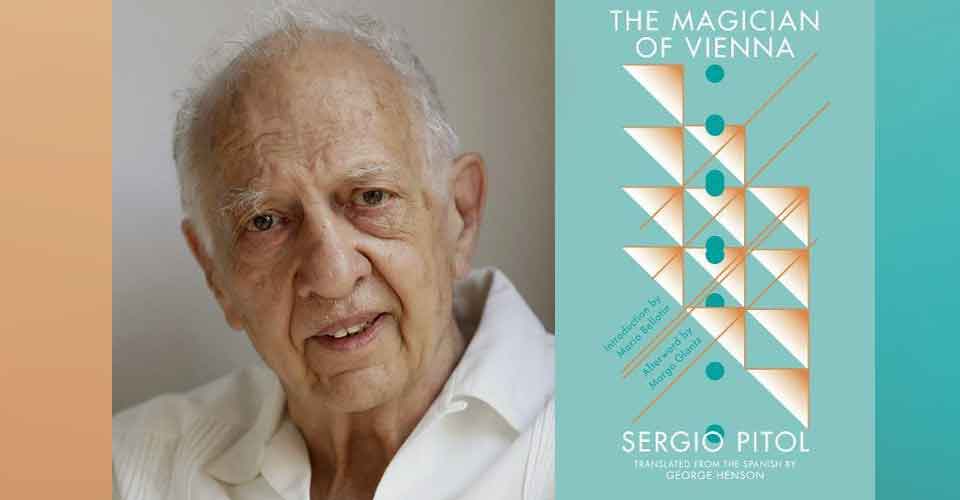

I think of his close friend of almost all his life, Margo Glantz, who wrote an afterword for my translation of The Magician of Vienna (Deep Vellum, 2017).

I think of the photo of him, together with Carlos Monsiváis and José Emilio Pacheco, the three Musketeers, in 1950s Mexico City, sitting on the floor, surely talking about the book that Monsiváis has in his hand.

I think of the adventures of these three great friends that fill The Art of Flight (Deep Vellum, 2015), the first volume of Pitol’s Trilogy of Memory, which I had the honor of translating.

I think of a trip to Mexico City three years ago, where I attempted to retrace the steps of Pitol in the Zona Rosa, of landing in front of the Bellinghausen restaurant, where Pitol lunched and dined, recalling the amusing episode he recounts in The Art of Flight, as tears welled up in my eyes as I tried to imagine him there some forty or so years before.

I think of the Edificio Río de Janeiro in Colonia Roma, often called the “House of the Witches,” which I stumbled upon by accident but immediately identified as the setting for Pitol’s novel Love’s Parade, which won the Herralde Novel Prize.

I think of Luz Fernández de Alba, a former student and now scholar of Pitol, who lives in the very house that belonged to her teacher and who looked for me at the Palacio de Minería Book Fair after learning that Pitol’s translator was there. “I had to meet you,” she told me, “to say thank you because I know he cannot.”

I think of Elena Poniatowska, his friend of fifty years, who regaled me with stories at her home in Chimalistac, during that same visit to Mexico City in March. I think of the look of sadness that filled her eyes when suddenly she spoke of the bleak reality of his illness, which had robbed him of language.

More than anything else, I think of my relationship with the man I considered my teacher, whom I’ve had the enormous responsibility of translating into English, and whom, unfortunately, I was never able to meet.

I think of his family, his cousin Luis, to whom he dedicated the beautiful story “Cemetery of Thrushes,” the translation of which I am now revising, of his nieces María and Laura, especially Laura, with whom I’ve maintained a pleasant correspondence about her uncle and to whom I had written two days before he died to tell her that my translation of The Magician of Vienna, the third volume in his Trilogy of Memory, had been longlisted for the Best Translated Book Award.

But more than anything else, I think of my relationship with the man I considered my teacher, whom I’ve had the enormous responsibility of translating into English, and whom, unfortunately, I was never able to meet. I think of the only communication I had with him, an email surely typed by his secretary, which arrived directly from his personal account: “Your interest in my work fills me with happiness and gratitude. I would love nothing more than to see my Trilogy of Memory translated into English, a language that I adore and in which none of my books exists.”

The responsibility of introducing a writer of Pitol’s importance to an English-speaking readership has never weighed on me more. I will not attempt to explain here—in fact, there is no clear explanation—why Pitol’s books had not been already been translated when, five years ago, WLT’s managing editor, Michelle Johnson, sent me an article she’d read in Granta, “The Best Untranslated Writers,” penned by the Mexican novelist Valeria Luiselli.

* * *

In the hours immediately after his death, messages of condolence came from all over the world, from readers, fellow translators, and writers. “We know how much you loved him, and we are very sorry for him and for you. We’re sending hugs,” wrote Alberto Chimal and Raquel Castro, whose words have filled the pages of WLT in my translation.

“Dear George, yesterday I wanted to write to congratulate you for being on the longlist of the BTBA. Today I am writing to tell you that I am very sorry for Pitol’s death, with whom the bond of translation and friendship unites you,” consoled the talented young Mexican novelist Daniel Saldaña in an email.

But the consolation that has touched me most is one sent to me by a reader who discovered the Maestro through my translations: “Thanks for everything you did so that I could read him; I would be sad, now, if I hadn’t.”

* * *

In the days following his death, the eyes of the entirety of the literary world were finally, rightly, on Pitol, with fitting obituaries in the New York Times and the Washington Post, testaments to his import, with passing references to the works I have translated. Before, my books were known only to devotees of translated literature.

The literary firmament has lost one of its most brilliant stars, but the brilliance of his work will never be extinguished.

Suddenly, interest in his Trilogy of Memory seemed to be growing exponentially.

Suddenly, I recalled every doubt, every second guess I’d had as I translated his books.

Suddenly, the Italian adage traduttore, traditore was no longer a joke, a mere play on words; it had become my accuser. I would be discovered. My deception would be exposed. I wasn’t a translator; I was a traitor.

The literary firmament has lost one of its most brilliant stars, but the brilliance of his work will never be extinguished. I am humbled if I have had even a small hand in that.

* * *

In a piece entitled “Farewell, Sergio Pitol,” which I had the honor to translate for the Paris Review, Elena Poniatowska eulogized her friend:

He was a magician, perhaps the one in his book The Magician of Vienna, the man with a thousand eyes that fly like doves toward every horizon, carrying letters in their beaks, crossing every ocean. This is why one hears a rush of wings around Sergio Pitol.

The great Spanish poet Federico García Lorca concludes the elegy for his friend, the bullfighter Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, with these poignant verses: “I sing his elegance with words that moan / and I recall the sad breeze through the olive grove.” Just now, as I think of those lines, I can hear a sad rush of wings.

Descanse en paz, Maestro.

University of Oklahoma