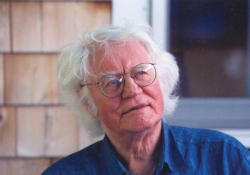

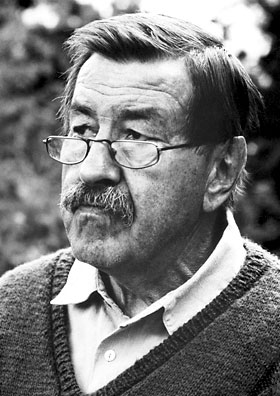

A Tribute to Günter Grass (1927–2015)

When it was announced on Monday that Nobel laureate Günter Grass had passed away in Lübeck, Germany, at the age of eighty-seven, we asked longtime WLT contributor Theodore Ziolkowski to offer a few words of tribute. We also reprint on the WLT website Dr. Ziolkowski’s earlier essay on Grass, written shortly after the German writer won the Nobel Prize in 1999. In the 1980s, Grass was twice nominated for the Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

With the death of Günter Grass on April 13, 2015, in a clinic in the northern German city of Lübeck, it may be fairly said that an era came to its end. With few exceptions—notably the novelist Martin Walser—Grass was the last surviving member of that early generation of writers associated with Gruppe 47, which dominated the German literary scene in the second half of the twentieth century: Nobel Prize winner Heinrich Böll, Uwe Johnson, and Siegfried Lenz, among others. Unlike the younger writers whose names feature prominently today, Grass and his contemporaries belonged to the twentieth century and the problems stemming from World War II. Characteristically, one of Grass’s final fictional works, entitled My Century (Mein Jahrhundert, 1999), was devoted to those decades.

After receiving the Nobel Prize in 1999, Grass continued an active career—but not with the powerful and linguistically innovative fiction for which he was renowned. In the twenty-first century Grass published only one fictional work, the novella Crabwalk (Im Krebsgang, 2002), which—in the technique familiar from his earlier novels—intertwined an autobiographically colored fiction with history: the assassination of the Nazi Wilhelm Gutzloff in 1936 by the Jewish student David Frankfurter and the 1945 sinking of the German ship named for Gutzloff by a Soviet submarine. The story is tied to Grass’s earlier novels Cat and Mouse (Katz und Maus, 1961) and Dog Years (Hundejahre, 1963) by the figure of Tulla Pokriefke, the mother of the fictional narrator.

Otherwise, Grass’s frequent publications during the past fifteen years consisted essentially of several volumes of poetry and three volumes of his autobiography. Only the first of these, Peeling the Onion (Beim Häuten der Zwiebel, 2006)—which recounts his life up to the composition of the novel that instantly established his reputation, The Tin Drum (Die Blechtrommel,1959)—follows a fairly traditional narrative line. In The Box (Die Box,2008), conversations with and among Grass’s eight children recount episodes from their childhood and their impressions of their father, many of them prompted by photographs made by an old “box” camera. Grimms’ Words (Grimms Wörter, 2010), finally, which amounts to Grass’s “declaration of love” for the German language, is for the most part a lively biographical account of the Grimm Brothers and their monumental dictionary.

It was not so much his writings as his often controversial and sometimes outrageous political views that kept Grass in the headlines. He enjoyed polemics and carried on an extended battle with his detested enemy, the cultural journalists who often criticized him—most notably the critic Marcel Reich-Ranicki. Many of his works, like The Tin Drum, forced readers to confront Germany’s Nazi past, and he expressed his disillusionment with Western values—notably Germany’s growing capitalism—in such novels as Local Anaesthetic (Örtlich betäubt, 1966). His antimilitaristic views led him to oppose the deployment of American nuclear weapons in Germany. Given his pronounced socialist tendencies, he early defended such leftist governments as Fidel Castro’s Cuba and the Sandinistas of Nicaragua. In 1989 he surprised much of the public with his opposition to the reunification of the two Germanies, arguing in favor of a loose cultural federation embracing both political entities.

Many readers, who regarded as hypocritical his constant political hectoring, which sometimes degenerated to self-righteous scolding, felt confirmed in their opinion when he revealed in his 2006 biography that he had been a member of the Waffen SS and, in that notorious organization, served as a tank gunner. Others sought to exonerate him on the basis of his youth at the time. In either case, Grass was now compelled to confront as part of his own biography the Nazi past with which he had so often challenged the German public.

Like Thomas Mann, who remained politically engaged through two world wars, Grass’s oeuvre embraced the entire scope of modern German, and indeed Western, history and culture.

Then in 2012 Grass published a poem that seemed to document the suspicion of anti-Semitism that had long shadowed him. In the poem “What Must Be Said” (Was gesagt werden muß), he criticized the West for what he termed its hypocrisy in supporting Israel with its nuclear potential and aggressive stance toward Iran, a country that, decades earlier, he had supported in its war with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. He argued that Germany should not provide Israel with submarines capable of launching nuclear warheads and, moreover, that international agencies should authorize Iranian nuclear sites. Predictably, the poem elicited a vigorous response from Prime Minister Netanyahu, and the Israeli government declared him persona non grata.

A few weeks later Grass published another poem, “Europe’s Shame” (Europas Schande), in which he attacked the European Union for its treatment of Greece, the home of Western civilization, by forcing Greece—like Socrates—to drink the fatal hemlock. In March 2015, finally, Grass attacked as racist the recent German political movement known as Pegida (an acronym meaning “Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the West”), arguing that the problem was not Islam but, rather, German political disputes.

Until the end, then, and for better or for worse, Grass, whose works belong unquestionably to the literary canon of the twentieth century, managed to keep himself in the limelight—if no longer through his literary achievements, then through his outspoken if controversial political views. To that extent his closest analogue among earlier German writers is a son of the same city where Grass spent his final years and died. Like Thomas Mann, who remained politically engaged through two world wars, Grass’s oeuvre embraced the entire scope of modern German, and indeed Western history and culture. His death evoked a chorus of accolades from prominent German cultural and political figures. His unmistakable voice, in literature as well as politics, will be missed.