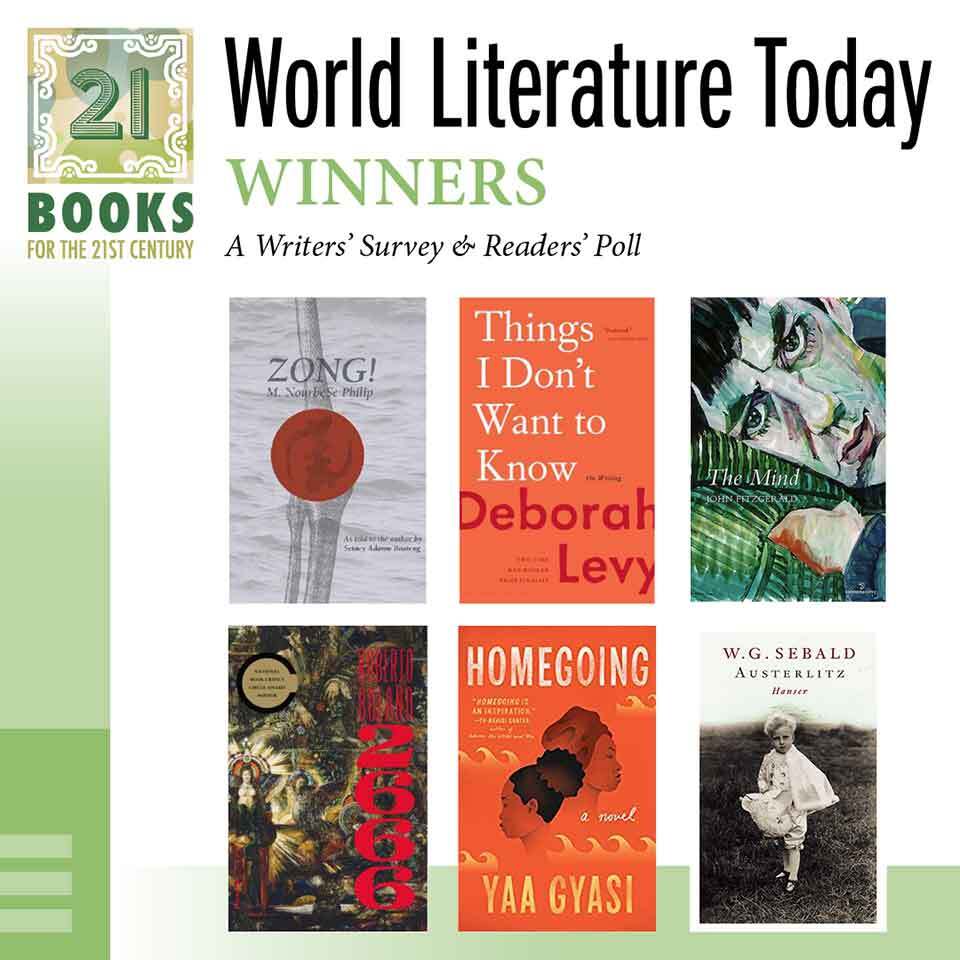

21 Books for the 21st Century: The Results of Our Readers’ Poll

Earlier this spring, the editors of WLT invited twenty-one writers to nominate a single book, published since the year 2000, that has had a major influence on their own work, along with a brief statement explaining their choice. We published the longlist and then invited readers to vote on their favorites. Here are the top vote recipients, followed by the respective nominating statements:

1. M. NourbeSe Philip, Zong!

2. Deborah Levy, Things I Don’t Want to Know: On Writing

3. John FitzGerald, The Mind

4. Roberto Bolaño, 2666

5. (tie) Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing, and W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz

To mark the occasion of Zong! winning the readers’ poll, M. NourbeSe Philip and Philip Metres recently took part in an email interview about the book. It will be published tomorrow on the WLT Weekly.

M. NourbeSe Philip

M. NourbeSe Philip

Zong!

Wesleyan University Press, 2008

I discovered M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! only after I’d written abu ghraib arias, when critics saw parallels in the work. Zong! is at once a brilliant documentary long poem and a sort of ritual exorcism of the demons of the slave trade. Built out of the language of the legal document of Gregson v. Gilbert, Zong! brings to light the murder of Africans on board a slave ship in 1781 for financial gain. The kidnapped and enslaved Africans had been purposely thrown overboard so that the owner of the Zong could benefit from his insurance policy. Philip’s visionary use of the burying language of law to recover the shreds of the voices of the lost is stark, elemental, and electrifying. It is poetry raised to the level of a truth commission. This work has launched a thousand poetic justice projects in the mode of documentary recovery. – Nominated by Philip Metres

Deborah Levy

Deborah Levy

Things I Don’t Want to Know: On Writing

Bloomsbury, 2014

“Living biographies” are the most poetic forms of fiction for writers, due to their highly demanding nature of fairness, truthfulness, and boldness. These powerful forces transform the writer in the most exposing and vulnerable ways. In my opinion, the centuries’ cost of bias and agony in the female collective consciousness makes living biography the most challenging work for women writers. That is why I chose Things I Don’t Want to Know as the most influential book written since 2000. Deborah Levy as a courageous and super-talented writer manages to challenge George Orwell with her sharp, witty tales in a very unassuming but determined way. She ensures and encourages, in her genuine way, my belonging to the human civilization’s female storytellers’ family, and yet she confirms that the gender-equal world “in letters” is not really far away. – Nominated by Buket Uzuner

John FitzGerald

John FitzGerald

The Mind

Salmon Poetry, 2011

I’m nominating The Mind, by John FitzGerald, because of the profound impact it had on me. The Mind is a collection so profound, extraordinary, and almost unbearably beautiful that I keep going back to it time and again to replenish my spirit. Its pattern is that of a circular labyrinth, which takes the reader to the heart or center of human consciousness through a series of nine philosophical journeys. This metaphysical labyrinth is a powerful meditation device, which not only brings solace but also transformation and healing. I could never be the same after reading The Mind. At the beginning, the poet is “Removed from the Center,” then experiences “Fear,” “Time,” “Beauty and Truth,” “Death,” “I,” “Prophesy,” “Rules,” “Choice,” and “A Mind Like the Wind,” before “Regaining the Center.” It delves into questions of identity, time, loss, grief, and death. This is the work of a master about the process of writing. The Mind is a remarkable, elegant collection of transcendental, primal beauty by a formidable poet, whose work never ceases to astound. – Nominated by Hélène Cardona

Roberto Bolaño

Roberto Bolaño

2666

Trans. Natasha Wimmer

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008

Both for literary as well as intimate reasons, I guess my pick should probably be 2666, by Roberto Bolaño. Albeit not my absolute favorite tittle from him (Distant Star, The Savage Detectives, or his short stories might rank even higher to my taste), nothing impressed me more than that monster when I was very young and it came out. Because it was an impossible book to write, more even so under the critical circumstances that it was written. The author’s health was fading, and his literary desire was growing. He had almost no time left, and therefore he chose the most ambitious mission he had ever attempted. That taught me a moving lesson on the power of fragility. Of being sharply aware of the value of every hour, every page, every conversation like this one. – Nominated by Andrés Neuman

Yaa Gyasi

Yaa Gyasi

Homegoing

Alfred A. Knopf, 2016

There are so many good books I can think of; this choice seems almost impossible. However, Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing is one of a kind, a tale that weaves both the personal and the political, that traces the historical divergences of two sisters, raised on two different continents. Each chapter is self-contained and populated with new characters in a long line of generations; the language is evocative, poetic, and thrusts us into the narrative immediately. Each character, however temporary, is treated with such care, such tenderness, that we cannot help but fall in love, throughout the entire book. The elements of nature, too, show up unexpectedly, and bodies and entire lineages are both contained and uncontained, held and set free on the page, their stories told from different perspectives. It is truly a masterpiece of storytelling and an important work of literature that bridges the gap between the African and the African American experience. Beautifully written and hauntingly executed, it still remains with me till this day. – Nominated by Mahtem Shiferraw

W. G. Sebald

W. G. Sebald

Austerlitz

Trans. Anthea Bell

Random House, 2001

This, the last of Sebald’s novels, is (like his others) a powerfully affecting excavation of the layered and suppressed history of the Second World War and of the ways that history thoroughly permeated the second half of the twentieth century. His fiction is an act of resistance against forgetting—and the story of Jacques Austerlitz, who for much of his life didn’t even know his parents were Prague Jews, is painfully close to reality. Consider, for example, the acclaimed British playwright Tom Stoppard, whose parents were, like Austerlitz’s, Czech Jews, and yet who did not know until the 1990s that he was Jewish, and that many of his relatives had perished in the Holocaust. Sebald is significant for me not only on account of his profound and urgent subject matter but also for his stylistic importance, for his insistence on an aesthetic rigor that eschews the omniscient third-person narrator (for moral reasons, among others) and yet finds a way forward for “realism.” In his hands, the first person is not consigned to autofiction, is not solipsistic, is not constrained by hollow and artificial conventions of scene setting. With Thomas Bernhard as his antecedent, Sebald took up Pound’s exhortation to “make it new” and offered compelling, original possibilities for the novel form. – Nominated by Claire Messud