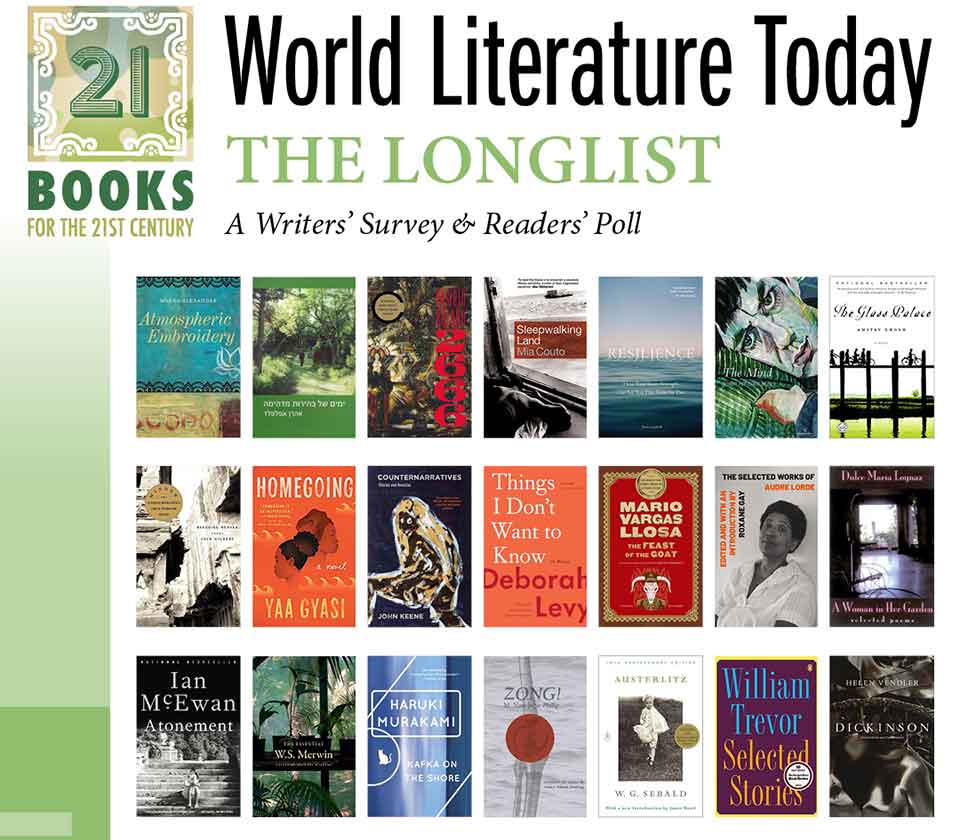

21 Books for the 21st Century: The Longlist

Earlier this spring, the editors of WLT invited twenty-one writers to nominate one book, published since the year 2000, that has had a major influence on their own work, along with a brief statement explaining their choice. Now it’s your turn to vote for your favorites during our two-week contest (April 1–15). Participating voters will be included in a drawing to receive a copy of the 1st-place book, and the top 5 list will be published in the summer issue.

The poll is now closed. Results will be announced in the Summer 2021 issue!

Meena Alexander

Meena Alexander

Atmospheric Embroidery: Poems

Triquarterly, 2018

The spine of Atmospheric Embroidery is Indian Ocean Blues, which traces the poet’s sea voyage from India to Sudan as a child and probes my own diasporic obsessions with loss and longing, along with a return to what we sometimes “cannot bear to remember.” Uneasy dwelling places, her poems, like mine, spring from rupture and craving. This was her final book, but narratives of exile and themes of dislocation, identity, memory, and belonging also preoccupied Alexander throughout her life, as did the language and shape of self-invention and provisional spaces. She, like me, finds herself in many places all at once, marked—and yet oddly sustained—by fractured and shifting multiplicities. – Nominated by Shahilla Shariff

Aharon Appelfeld

Aharon Appelfeld

Days of Astonishing Brightness (in Hebrew)

Kinneret Zmora–Bitan Dvir, 2014

I read Aharon Appelfeld’s Yamim Shel Behirut Madhima (Days of astonishing brightness) quickly, but it has stayed deep within me ever since. The novel is a solo journey home, after the concentration camps are liberated, and there are glimpses of burned cars and abandoned military equipment along the roads, but the real journey is a voyage within the narrator’s mind and memory. The novel immerses us in a prewar world, with its intricate evocation of a beloved mother’s inner life—detailing how she took refuge in monasteries and churches when the narrator was a child. I have thought of the simple structure of a lone traveler’s journey, the comfort with interfaith material, and the complicated interior world of a young man traveling to a home and a mother who almost certainly no longer exist as I work on my own book based on a long journey, and a complex interfaith voyage deep within. – Nominated by Aviya Kushner

Roberto Bolaño

Roberto Bolaño

2666

Trans. Natasha Wimmer

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008

Both for literary as well as intimate reasons, I guess my pick should probably be 2666, by Roberto Bolaño. Albeit not my absolute favorite tittle from him (Distant Star, The Savage Detectives, or his short stories might rank even higher to my taste), nothing impressed me more than that monster when I was very young and it came out. Because it was an impossible book to write, more even so under the critical circumstances that it was written. The author’s health was fading, and his literary desire was growing. He had almost no time left, and therefore he chose the most ambitious mission he had ever attempted. That taught me a moving lesson on the power of fragility. Of being sharply aware of the value of every hour, every page, every conversation like this one. – Nominated by Andrés Neuman

Mia Couto

Mia Couto

Sleepwalking Land

Trans. David Brookshaw

Serpent’s Tail, 2006

My recommendation is the amazing novel Sleepwalking Land (2006), by Mozambique writer Mia Couto. An amazing multilayered metanarrative (a book within a book), historical (recent history blended with an attempt at mythic memory), hero’s quest, intergenerational trauma and healing. It is at once a detective story, a story of a war-torn land seeking self and healing, a history of people told from the inside and from a time before the advent of colonialism, a ghost story. Genre bending, nonbinary, and resisting definition, this book opens the reader’s deepest empathy without sentimentalism. Even in translation to English, the language here is sublime; the form imitates orality within the limitations of the written. This book gave me permission as a writer and hope for the work of African writers—to be the curators of our continent’s humanity. – Nominated by Chris Abani

Boris Cyrulnik

Boris Cyrulnik

Resilience: How Your Inner Strength Can Set You Free from the Past

Jeremy P. Tarcher / Penguin, 2011

This book was sent to me by an unnamed person, or at least, I have long lost the letter and therefore the name of the person who sent it to me, quite unsolicited. It arrived after I had written a memoir about my country of Sierra Leone, the war there, and the 1975 murder of my father, who was a political activist. I read Resilience and recognized myself in many of the descriptions of survivors. Cyrulnik, who is well-known in his native France, escaped deportation to the Nazi death camps as a child, joined the Resistance, and later became a psychologist, specializing in the treatment of trauma. Cyrulnik believed that a person’s future is not defined by the events of their past. In an age of victimhood, his ideas may struggle to find purchase, though I have found that the truly traumatized find comfort in his ideas. Beyond that Cyrulnik’s work has influenced much of my own, in particular my latest novel, Happiness. – Nominated by Aminatta Forna

John FitzGerald

John FitzGerald

The Mind

Salmon Poetry, 2011

I’m nominating The Mind, by John FitzGerald, because of the profound impact it had on me. The Mind is a collection so profound, extraordinary, and almost unbearably beautiful that I keep going back to it time and again to replenish my spirit. Its pattern is that of a circular labyrinth, which takes the reader to the heart or center of human consciousness through a series of nine philosophical journeys. This metaphysical labyrinth is a powerful meditation device, which not only brings solace but also transformation and healing. I could never be the same after reading The Mind. At the beginning, the poet is “Removed from the Center,” then experiences “Fear,” “Time,” “Beauty and Truth,” “Death,” “I,” “Prophesy,” “Rules,” “Choice,” and “A Mind Like the Wind,” before “Regaining the Center.” It delves into questions of identity, time, loss, grief, and death. This is the work of a master about the process of writing. The Mind is a remarkable, elegant collection of transcendental, primal beauty by a formidable poet, whose work never ceases to astound. – Nominated by Hélène Cardona

Amitav Ghosh

Amitav Ghosh

The Glass Palace

Random House, 2000

This is a novel set in Burma, India, and Malaya and is a work of historical fiction. The story begins with the fall of the Konbaung dynasty in Mandalay and their subsequent exile to Ratnagiri, India; it is a sweeping saga of the colonial and regional forces that have shaped modern India, Myanmar, and Malaysia. My own work focuses on Asian societies and their transnational exchanges, and Ghosh provides a masterclass in this book—despite some flaws that weigh down the latter half—on how to write commemoration, memory, and history into a compelling work of fiction. – Nominated by Dipika Mukherjee

Jack Gilbert

Jack Gilbert

Refusing Heaven

Alfred A. Knopf, 2005

Jack Gilbert is a rare poet: relentlessly romantic, savagely honest, and utterly relatable. What I love about him the most and draw inspiration from is his uncanny ability to take pleasure in remembering—even if the memory is devasting and gray. “To make injustice the only measure of our attention,” he writes, “is to praise the Devil.” I repeat that line to myself every day. – Nominated by Sholeh Wolpé

Yaa Gyasi

Yaa Gyasi

Homegoing

Alfred A. Knopf, 2016

There are so many good books I can think of; this choice seems almost impossible. However, Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing is one of a kind, a tale that weaves both the personal and the political, that traces the historical divergences of two sisters, raised on two different continents. Each chapter is self-contained and populated with new characters in a long line of generations; the language is evocative, poetic, and thrusts us into the narrative immediately. Each character, however temporary, is treated with such care, such tenderness, that we cannot help but fall in love, throughout the entire book. The elements of nature, too, show up unexpectedly, and bodies and entire lineages are both contained and uncontained, held and set free on the page, their stories told from different perspectives. It is truly a masterpiece of storytelling and an important work of literature that bridges the gap between the African and the African American experience. Beautifully written and hauntingly executed, it still remains with me till this day. – Nominated by Mahtem Shiferraw

John Keene

John Keene

Counternarratives

New Directions, 2015

In response to the question we’ve been asked to answer, I confess I can’t discern yet, if I ever will, exactly how John Keene’s book of short fictions has influenced my writing, but I know that Counternarratives reassembled my brain, much in the way of my first encounter with Jorge Luis Borges half a lifetime ago. Keene is a poet and translator; one could try to explain the preternatural precision and capaciousness of his fiction by resort to his other arts. While those must have allowed him to hone some special territories of knowledge, perhaps giving heft and range to his formal experiments, for example, the stories and novellas in Counternarratives offer some of the profoundest satisfactions to be found in English-language prose. Each story in the book is an act of reading, or rereading, history and literature, ranging from stories of Brazil through the US and elsewhere, with the book’s reader somehow, alchemically, brought along. I admit to a particular interest in Keene’s topics, but he has many admirers, so I’m sure my nomination doesn’t rest on special knowledge, even if that is one of the many delights of the collection. Perhaps every reader who loves a book thinks they love it best. I can say that each time I pick up this collection, I feel I am entering upon a ritual and can expect, reliably and cyclically, to be transformed. – Nominated by Padma Viswanathan

Deborah Levy

Deborah Levy

Things I Don’t Want to Know: On Writing

Bloomsbury, 2014

“Living biographies” are the most poetic forms of fiction for writers, due to their highly demanding nature of fairness, truthfulness, and boldness. These powerful forces transform the writer in the most exposing and vulnerable ways. In my opinion, the centuries’ cost of bias and agony in the female collective consciousness makes living biography the most challenging work for women writers. That is why I chose Things I Don’t Want to Know as the most influential book written since 2000. Deborah Levy as a courageous and super-talented writer manages to challenge George Orwell with her sharp, witty tales in a very unassuming but determined way. She ensures and encourages, in her genuine way, my belonging to the human civilization’s female storytellers’ family, and yet she confirms that the gender-equal world “in letters” is not really far away. – Nominated by Buket Uzuner

Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde

The Selected Works

Edited by Roxane Gay

W. W. Norton, 2020

I have lived so much of my life in fear of speaking because of possible repercussions. As a Black woman and child of immigrants, growing up in our anti-Black, antiwoman patriarchal society, the message I got just for existing, let alone speaking, was that I was wrong. In Sister Outsider, one of her collections of essays, Audre Lorde wrote of the importance of speaking despite fear, through fear. “I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared,” Lorde writes. All the courage I have in my writing, in life, begins with Audre Lorde and the writing that appears in her Selected Works. – Nominated by Hope Wabuke

Dulce María Loynaz

Dulce María Loynaz

A Woman in Her Garden: Selected Poems

Trans. Judith Kerman

White Pine Press, 2002

There is a book of poems that I’ve returned to over and over during the past two decades. At least once every three months, I reread A Woman in Her Garden, by Dulce María Loynaz. It is a 2002 White Pine Press bilingual edition translated by Judith Kerman, with an exquisite afterword by Ruth Behar. My favorite poem in the entire world lives on pages 82 and 83: “En mi verso soy libre / In my poem I am free.” I can’t imagine my own body of work for young readers existing without this poem as a vision of freedom to experiment. – Nominated by Margarita Engle

Ian McEwan

Ian McEwan

Atonement

Nan A. Talese / Doubleday, 2002

It might seem a very apparent choice, but I can’t help suggesting this novel—one of my biggest reading impressions among the latest twenty years’ fiction. It gives a reader an awesome (in the old sense) glimpse into the unfathomableness of human consciousness. How do we make suggestions, what really defines our opinions, and why do our memories sometimes turn out to be false? In this novel, troubling and topical scientific questions of our psychology found an artistic embodiment in a brilliant personal story of crime and self-punishment. – Nominated by Alisa Ganieva

W. S. Merwin

W. S. Merwin

The Essential W. S. Merwin

Ed. Michael Wiegers

Copper Canyon Press, 2017

I have been reading William Merwin’s work since 1970, so many of these poems were old friends already. This is a truly gorgeous edition which opens with magnificent photographs. Poetry as a refuge—a respite—a quiet grove of considerations. William’s crucial, exquisite poetry has never failed to transport a reader both inward and outward at once, with conviction and clarity and a full embrace of the mystery we live within. It has heartened me in the worst of times and thrilled and expanded me, always. It has enlarged the breath and breath is what we need to speak anything at all. – Nominated by Naomi Shihab Nye

Haruki Murakami

Haruki Murakami

Kafka on the Shore

Trans. Philip Gabriel

Alfred A. Knopf, 2005

I never perceive influences of any kind in my writing. Influences flow underwater, and who knows what emerges when we allow our imagination to work on its own. As a very eclectic reader (science, philosophy, anthropology, psychology), it all appeals to me in different manners and most certainly contributes to my fiction writing. Literature is in the first place, and there are quite a few wonderful novels published this century that I would gladly recommend, but as influences go I can only think of Kafka on the Shore, by Haruki Murakami. Written in 2002, I read it around 2008 in Spanish translation. It was the first Murakami work that fell into my hands, and it hit me hard: surprising, enchanting, reinforcing a path I love to follow. A new twist to Alejo Carpentier’s “marvelous real,” the perfect mise-en-page of the Iroquois dictum to see the world twice, simultaneously, with the forward gaze so as not to miss any minor detail and the lateral gaze to capture the scurrying shadows. – Nominated by Luisa Valenzuela

M. NourbeSe Philip

M. NourbeSe Philip

Zong!

Wesleyan University Press, 2008

I discovered M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! only after I’d written abu ghraib arias, when critics saw parallels in the work. Zong! is at once a brilliant documentary long poem and a sort of ritual exorcism of the demons of the slave trade. Built out of the language of the legal document of Gregson v. Gilbert, Zong! brings to light the murder of Africans on board a slave ship in 1781 for financial gain. The kidnapped and enslaved Africans had been purposely thrown overboard so that the owner of the Zong could benefit from his insurance policy. Philip’s visionary use of the burying language of law to recover the shreds of the voices of the lost is stark, elemental, and electrifying. It is poetry raised to the level of a truth commission. This work has launched a thousand poetic justice projects in the mode of documentary recovery. – Nominated by Philip Metres

W. G. Sebald

W. G. Sebald

Austerlitz

Trans. Anthea Bell

Random House, 2001

This, the last of Sebald’s novels, is (like his others) a powerfully affecting excavation of the layered and suppressed history of the Second World War and of the ways that history thoroughly permeated the second half of the twentieth century. His fiction is an act of resistance against forgetting—and the story of Jacques Austerlitz, who for much of his life didn’t even know his parents were Prague Jews, is painfully close to reality. Consider, for example, the acclaimed British playwright Tom Stoppard, whose parents were, like Austerlitz’s, Czech Jews, and yet who did not know until the 1990s that he was Jewish, and that many of his relatives had perished in the Holocaust. Sebald is significant for me not only on account of his profound and urgent subject matter but also for his stylistic importance, for his insistence on an aesthetic rigor that eschews the omniscient third-person narrator (for moral reasons, among others) and yet finds a way forward for “realism.” In his hands, the first person is not consigned to autofiction, is not solipsistic, is not constrained by hollow and artificial conventions of scene setting. With Thomas Bernhard as his antecedent, Sebald took up Pound’s exhortation to “make it new” and offered compelling, original possibilities for the novel form. – Nominated by Claire Messud

William Trevor

William Trevor

Selected Stories

Penguin, 2011

I have devoured everything written by William Trevor (1928–2016), but his Selected Stories remains a major influence for my own work. Reading the stories in this book reminds me why Trevor was a master of this genre. He has the uncanny ability to burrow deep into a character’s emotions while remaining utterly objective and without sacrificing wide-angled views that show the character as part of a neighborhood, a community, a city, and even the country (often Ireland but also England). I think Trevorites who’ve read stories such as “The Piano Tuner’s Wives” and “The Potato Dealer” know what I’m talking about. With each of Trevor’s stories, I feel that I am not only experiencing the world that he has created but also participating in the writing process, sentence by sentence. He is a writer’s writer, and when he passed away a few years ago, I felt that I had also lost a great teacher. – Nominated by Samrat Upadhyay

Mario Vargas Llosa

Mario Vargas Llosa

The Feast of the Goat

Trans. Edith Grossman

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001

Few writers have had such a long and prolific career as Mario Vargas Llosa. He’s been a very public figure for five decades and one of the most influential essayists, novelists, and intellectuals in the world. He is the only remaining living voice of the Boom generation, and most of his books are considered modern classics. For a long time, Vargas Llosa was obsessed with the origin of dictatorships. In 2000 he published La fiesta del chivo (Eng. The Feast of the Goat), a historical novel that explores the violent tradition of military power. The dictator in question is Rafael Leónidas Trujillo, an officer who seized power in the Dominican Republic in 1930 and held on to it until he was assassinated thirty-one years later. At first sight, Vargas Llosa seems to be studying the psychology of a tyrant: his vanity, nonexisting morality, and monstrous violence. But he does more than this. He goes deep into the collective memory of this continent. This is why The Feast of the Goat has been such an important influence in my work. Vargas Llosa’s technique is sharp as a blade: with a complex narrative structure, he manages to join the past and the present—as he did, brilliantly, in Conversation in the Cathedral—with the clear intention to remind us that violence in Latin America is circular and never-ending. – Nominated by Felipe Restrepo Pombo

Helen Vendler

Helen Vendler

Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries

Belknap Press, 2010

I’ve always been drawn to Emily Dickinson, but for many years I wasn’t sure of myself. Reading her poems felt daunting. With these 150 short, close readings, I’ve come to apprentice myself to Dickinson by way of reading on her craft and making up writing prompts for myself. Vendler’s work comes close to magic. – Nominated by Kimiko Hahn