Fighting the Rise of Digital Repression

A Q&A with Deji Olukotun

Deji Olukotun is PEN’s inaugural Freedom to Write Fellow, and he’s helping to lay a universal foundation at all PEN centers to protect and defend writers who are using digital technologies. A practicing human-rights attorney, he is also a passionate fiction writer with his novel Nigerians in Space to be published this winter by Ricochet Books. In this interview with Olukotun, we look at the current state of affairs in regards to the exponentially growing amount of digital freedom cases, and discover how PEN defends and enforces the freedom of expression for all writers across the globe.

Jennifer Rickard Blair: As PEN’s Freedom to Write Fellow, what type of work do you do in regards to the Digital Freedom initiative?

Deji Olukotun: My role is to advocate on behalf of writers who may be persecuted for using digital technologies—anything from Facebook to Twitter to email. When I first arrived at PEN, we had a sense that more writers were being arrested for using digital technologies, but we weren’t sure how many or how to go about stopping this trend. Working closely with an international team, I helped design the PEN Declaration on Digital Freedom to develop a set of principles for PEN Centers around the world to defend writers. We then had to do some hard work on the “back end,” namely to create a database that tracked these trends and then create some visualization tools to share them with the public. Now we have a system in place where we can rapidly respond to threats to writers both on- and offline.

JRB: What has been one of your most challenging cases in the past year?

DO: Mohammed al-Ajami is a Qatari poet who was given a fifteen-year jail sentence for two poems written in 2011. The thing is, the first poem, which discussed the Arab Spring in Tunisia, was secretly recorded in Egypt and posted on Facebook, so he didn’t even know about it. PEN sent a delegation to visit him in Qatar before his appeal hearing in October, but we were given the run-around and never had a chance to meet him, and his sentence was affirmed. Keep in mind, Qatar supports Al Jazeera, an otherwise liberal news network, and the country will be hosting the 2022 FIFA World Cup. They’re sending the wrong message to the world, and they should release al-Ajami as soon as possible.

JRB: How does the U.N. partner with you to advocate for writers in danger?

DO: We work with U.N. human-rights mechanisms such as the Human Rights Council to document human rights violations against writers and to press for reforms to support freedom of expression. In October, I traveled with Nigerian PEN deputy secretary-general Oluwafiropo and Independent Chinese PEN Center president Tienchi Martin to the Council to lobby delegations to stop the persecution of writers in Nigeria and China.

JRB: In your most recent blog post on the Huffington Post, you mention a case in which your team at PEN called on Yahoo to be held accountable for passing along the personal identifying information of Chinese writer and activist Shi Tao, information that led to his arrest and imprisonment. How do you leverage your communication with such monolithic organizations to achieve positive results?

DO: We try to effect change at all levels, whether at the grassroots level through letter-writing campaigns or at the policy level by advocating for changes in legislation. PEN recently joined the Global Network Initiative, a multistakeholder body that includes technology companies. This gives us the ability to approach these companies directly and work with partner NGOs to make sure they respect privacy, free expression, and human rights.

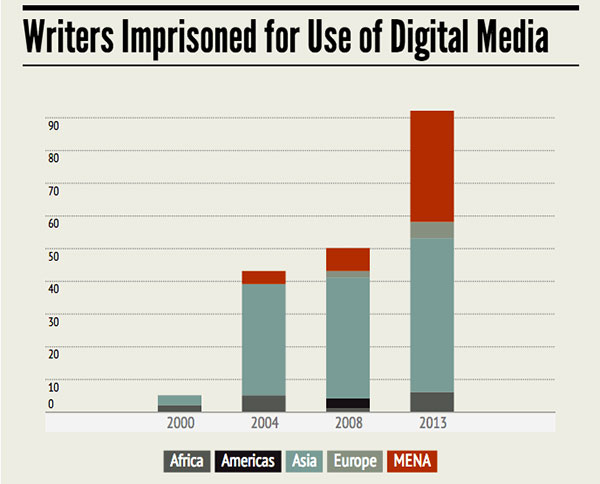

JRB: Your newly released Rise of Digital Repression infographic illustrates that nearly half (49.2 percent) of PEN’s cases are now digital media, a number that has been exponentially increasing since 2000, when these cases only made up 6.6 percent of your caseload. Do you expect the scales to tip come 2014, with more digital freedom cases than traditional media cases?

DO: Actually, with the new cases that we have been seeing, I think we’re already over 50 percent! As these technologies spread, more and more people are writing and speaking their minds, but few of them have digital security training to make sure they do so securely. And repressive regimes are increasingly cracking down on political dissent with sophisticated technologies—which are often made by Western companies. It’s a long, important fight ahead that will require a lot of thought and energy. These things aren’t going away in the short term.

JRB: Why are digital freedom cases rising in the Americas and in Europe?

DO: In Europe, the bulk of the coming cases are in Turkey, which we include on our caselist even though Turkey is not a member of the European Union. Despite achievements in other areas, Turkey routinely violates the right to free expression by jailing publishers and writers or putting them on trial. In the Americas region, we’ve seen a worrying rise in Brazil in particular, where blogger José Cristian Goés was put on trial for writing a post that lampooned a local official.

JRB: Should American writers be fearful of NSA surveillance?

DO: Our recent PEN report Chilling Effects proves that some of America’s leading writers are already self-censoring. This means that they are deciding not to write about or research certain controversial topics because they suspect they are being surveiled. 85 percent of writers responding to PEN’s survey are worried about government surveillance of Americans. This is extremely troubling because great literature often requires exploring controversial themes and portraying them from unconventional viewpoints. Writers already make choices about adding or eliding text to tell their stories—editing is part of the craft—so it’s especially bad that the NSA is narrowing the range of stories writers are willing to tell. Should the NSA effectively be playing the role of an editor? I don’t think so.

JRB: You yourself are also a writer and your novel Nigerians in Space was just launched. Does writing inform your advocacy work?

DO: Definitely! As a writer, I recognize the personal risk and hard work involved in writing a story and sharing it with an audience. For writers in repressive regimes, this is an even more courageous act because they can go to jail for it. I do explore themes of social justice in my writing, but I try to focus on telling a good story—Nigerians in Space is actually something of an international literary thriller.

JRB: Is there anything that WLT’s readers can do to help promote free expression around the world?

DO: Yes! If you are a writer, join PEN or come to one of our public events, such as our PEN World Voices Festival of International Literature in the Spring. And check out our website at http://www.pen.org/ to take action on behalf of writers.