Bones

Surely I owe this particular take on Bone Baroque to my postmodern, American-ironic, agnostic, death-denying, fragmented nonself as it glances backward from its twenty-first-century perch, writes Lauren K. Watel as she recalls her tour of a bone-filled crypt and reflects on objectification and the need to form order out of chaos.

Before the pandemic makes international travel a fraught enterprise, I fly across the ocean to live, for a brief interlude, among an accomplished group of scholars and artists in a last-century palace of higher learning. Designed by American architects, this elegant neoclassical edifice sits atop a hill overlooking the ancient city below, pale and spectral in the distance, and the legendary river winding through it. Surrounded by high walls, the building and grounds are accessible only via imposing wrought-iron gates. Accordingly, the palace employs a staff of gatekeepers: literal gatekeepers, meant to safeguard the property from thieves and other unsavory interlopers, and metaphorical gatekeepers, meant to safeguard the property from mediocrity.

It’s a city of bones, bones forever underfoot.

Outside the gates, however, an entire city awaits us, a city teeming with lofty, echoing churches and monuments and tourists and souvenirs and regal stray cats. And history, impossible to ignore, history jammed into every crack and crevice, history waiting around every corner, history bubbling out of the sewers, layers and layers of it, the city like a door that’s been painted over and over, a door thick with the centuries, millennia even. History waiting wherever anyone starts to dig, ancient ruins and relics revealed once the excavation starts, and don’t forget the bones. It’s a city of bones, bones forever underfoot, even buried, or so I’m told, below the garden of the palace, bones possibly lying underneath the very bench upon which I sit with notebook and scrambling pen, at the foot of this leafless tree, which reaches all its gnarled arms around me, as if to protect me from something ominous, myself perhaps.

In the spirit of intellectual and creative interchange encouraged at the palace, a young scholar of archaeology gives a talk one evening about ancient local funerary practices. In the past, she informs us, archaeologists would unearth tombs and graves to uncover, collect, document, and preserve the artifacts buried with the bodies. These included roof shingles laid over the graves to provide shelter for the corpses, as well as so-called libation tubes, which were inserted into graves at the time of burial so that the living could literally pour liquid offerings into the tube, to honor and maintain a connection with the dead. These human-made creations were historically of great scholarly interest, while the human remains these artifacts were meant to protect and venerate were of no interest to the excellent professionals, with their shovels and brushes, notational tools and photographic equipment, all in the name of contributing to the ever-bulging sum of human knowledge. As a consequence, before the mid-twentieth century, archaeologists simply disposed of any corporeal remnants. In other words, they kept the objects and dumped the bones.

In contrast to these antiquated predecessors, tonight’s scholar repeatedly emphasizes her enlightened interest in these previously ignored bodies. Especially the bodies of, as the speaker puts it, nonelites: women and children and farmers and slaves. The body in all its body-ness presumably returning humanity to the study of funereal practices. I ask the speaker if this relatively new scholarly practice of considering the bodies constitutes a link between the archaeologist and the corpse akin to the libation tube, which connected the living and the dead. “Absolutely not,” the speaker quite emphatically replies. As there is an ethical consideration troubling every exhumation, she prefers to take a more neutral stance toward the bodies, which to her are objects of study. “We are grave robbers,” she says.

Sitting in my chair in the lecture room after the talk concludes, I feel vaguely disconcerted by her answer. If archaeologists are so concerned with the bones of nonelites, why would they intentionally view them as “objects,” rather than as human remains? And why does the supposed neutrality of the human relic-as-object somehow skirt the ethical delicacy of grave robbing? The least they could do as an act of humility and apology was to acknowledge that what they’re digging up in the name of human knowledge is, or was, even if long ago, human. That they are, in every way, interlopers, even if the government in question gave them permission to dig up, uncover, remove, expose, and catalog an object that was once a subject. A subject who, more than likely, would not have appreciated, while alive, the idea that far off in the future some educated, earnest young scholar from a bustling, bumbling future country called America would cross the ocean and troop out to some countryside plot, where the person’s remains had been lying peacefully under their shield of roof shingles and the libation tube for centuries, and dig the person up. That person now a nonelite object of study, an exhumed set of leg bones with an arm bone thrown in—how “humerus,” or so goes the archaeological joke.

As I understand it from my layperson’s grasp of object-relations theory, one cannot study that which is fused with oneself.

I suppose, on one hand, that it might be helpful, even preferable, to untangle our own living humanness from the dead humanness of an ancient assortment of anonymous, nonelite bones in order to study “practices” and “customs.” As I understand it from my layperson’s grasp of object-relations theory, one cannot study that which is fused with oneself. In order to see something clearly, to reflect upon its meaning, that thing must be other-than-self or outside-of-self. In other words, object. One cannot study something without seeing it as separate from oneself. Even to see oneself one must step outside of one’s self, somehow, must develop another self that regards the self as object in order to see and study it. Objectification in this case is a necessary component of growth.

And yet, as all the scholars and artists shamble up to the bar for bubbly and conversation, I can’t help but feel a profound unease at the easy designation of objecthood for those nonelite bones, that humerus. I feel how easily my own objecthood could fold over me, perhaps while I’m still living in my bones, which would be considered elite by the standards of our time, given the shade of my skin and my level of education, but which would have been considered offensive, dangerous, expendable had I lived, and died, as my ancestors did, in Europe before and during World War II.

How much objectification is too much? Complete objectification makes it possible for one person to overlook another person’s humanity and therefore to harm them without remorse. If we easily forget the humanity of ancient nonelite bones, how long before we forget the humanity of the bones inside the living body sitting across from us at the table? In fact, it’s happening all the time, this denial of humanity, this conferring of objecthood on others in order to justify scorn and superiority, which leads to persecution in all its forms.

At a certain point, objectification becomes a fatal kind of blindness.

Are we so fragile in our subjecthood that we must constantly objectify others as “other,” so that against their objecthood and otherness our own subjecthood becomes visible to us? Is this all it comes down to? And it melts up, from objecthood as your wrong-thinking neighbor to objecthood enshrined as policy, the laws and traditions and assumptions that subtly yet effectively sew the durable threads of oppression into the very fabric of our living. If a certain degree of objectification is necessary in order to see something, to examine it and to change oneself in relation to it, at a certain point objectification becomes a fatal kind of blindness, a way not to see the humanity right in front of you, so that the object is no longer worthy of study but worthy only of extermination.

* * *

Today the sun is out in full force, the sky a pale, standoffish blue, a blue suggesting winter’s stealth approach, the withholding chill of leaner times. We descend the hill and cross the river to attend a concert of seventeenth-century liturgical choral music at one of the city’s innumerable churches, this one built during the same era the music was composed. Unbeknownst to us, the price of a ticket includes a tour of the church museum, devoted to the history of the Christian order of monks who worshipped in the church. Before we are allowed into the sanctuary and the concert, we are herded through the museum and subjected to lengthy lectures on the objects and practices and personages of this order. These include various instruments of self-flagellation, holy dolls bundled below the chin like burritos, and the order’s coat of arms, which depicts two literal arms, one bare, one clad in a brown sleeve.

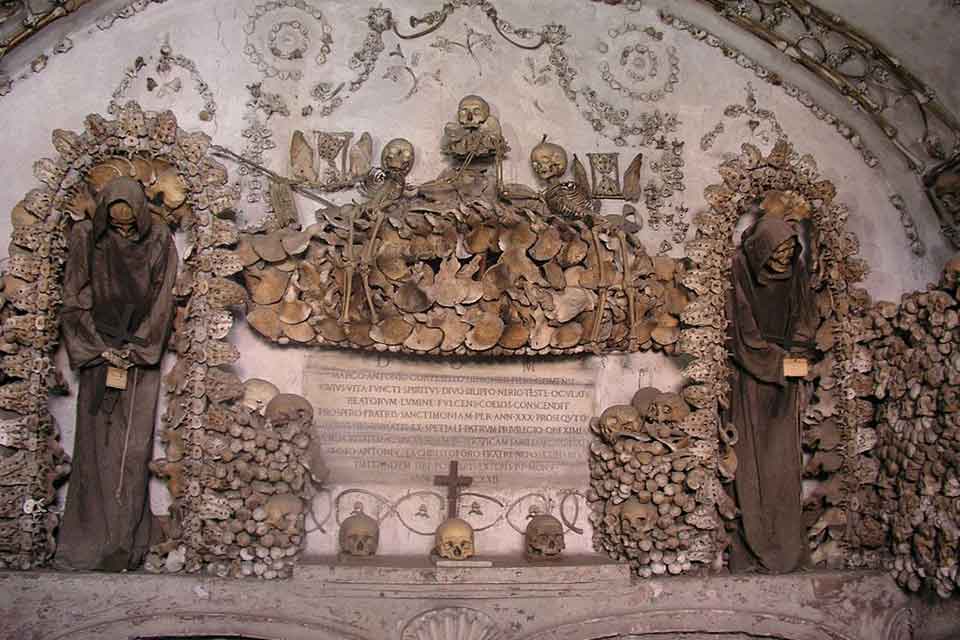

Even stranger, the tour ends in the order’s crypt, where we encounter a series of small, interconnected underground rooms elaborately arrayed with bones. Human bones, which cover the walls and ceilings. Here the skull chapel; there the tibia and fibula chapel. Tens of thousands of bones—from the corpses of the order’s long-gone friars, our guide informs us—serve as architectural ornament, meticulously arranged as the tesserae in a mosaic. In addition, whole skeletons, clothed in the brown-hooded robe characteristic of that particular order, have been posed throughout the crypt in attitudes of prayer and triumph.

Tens of thousands of bones—from the corpses of the order’s long-gone friars, our guide informs us—serve as architectural ornament, meticulously arranged as the tesserae in a mosaic.

The more death-sensitive members of our tour group rush queasily through, while two furious men in suits assail a woman snapping pictures with her phone. Photographs of the crypt are strictly forbidden, as indicated by signs at the entrance. The men scream at the woman in outraged accents, “Delete! Delete! But you did not delete!” And the woman, rather than saying, “Of course, I’m sorry, I didn’t know pictures were forbidden,” instead bitterly complains, “But you’re not making anyone else delete their pictures. Why are you picking on me?”

I wander utterly transfixed through these tiny bone-studded chambers, the way lit by dimly bulbed bone chandeliers. In one chapel a child-sized skeleton, holding a scale and scythe, stares down like a fleshless cherub from an ovular decorative ceiling medallion made of vertebrae. As if to confirm the perversity of the whole experience, I spot a quote on the wall from the Marquis de Sade, who laments that sunlight coming through the windows blunted the creepy effect. Why didn’t he visit at night? one wonders. At any event, once I get used to the strangeness, I find it doesn’t bother me to be surrounded by so many artfully arranged bones; on the contrary, the whole spectacle starts to seem funny in a way. The skeletons of long-deceased monks dressed up as monks remind me of nothing more than characters in a cartoon, the whole thing like a macabre joke-installation, with its kitschy use of death as decorative motif, rather like a bone version of the gaudily colorful pleated fabric covering the walls and ceiling of the billiards room at Graceland.

Surely I owe this particular take on Bone Baroque to my postmodern, American-ironic, agnostic, death-denying, fragmented nonself as it glances backward from its twenty-first-century perch. I wonder what effect this scene would have had on people contemporaneous with its making. Would it have scared them, reminded them of their mortality? Would it have encouraged, somehow, the glorification of God and the splendor of the afterlife? Would it have inspired them to celebrate the incorrigible human will to live with the presence of death? To answer these questions, I could surely do some research. Perhaps I will. Though probably not, decontextualizing and reading through my own severely limited lens being more my style.

The more time I spend in the crypt’s gruesome extravagance, the less ironic distance I feel, and the more unease.

The more time I spend in the crypt’s gruesome extravagance, the less ironic distance I feel, and the more unease. Though all these bones have been assembled in ornate patterns to adorn a space considered sacred, the fact that they’ve been sorted and fit together like so many Legos ends up robbing the bones of their sacredness. To transform bones into a decorative material, like paint or plaster or stone, feels like a violation of the body’s humanity. To arrange bones like with like, disassembling the bodies for their spare parts like old car bodies in the junkyard, feels like a violation of the body’s integrity as body. Even an intact skeleton possesses an integrity of its own. But the crypt’s intact skeletons, dressed in their robes and posed in their attitudes, also seem robbed of dignity, dressing and posing something a child does with dolls and action figures.

As I contemplate the archways of skulls and scapulae, the meticulous arrangement of the bones, the sense of composition and narrative, the close attention to detail, my unease only increases. I can’t help but think of my own tendencies toward ordering and arranging. Ever since I can remember, I’ve felt a compulsion to organize not only my surroundings—as a child I regularly cleaned out and sorted my closet, rearranged my shelves of books and stuffed animals, and created museum-like exhibitions of topics of interest in my bedroom—but also my family and friends. After my father committed suicide when I was eighteen, I was even more forcefully driven by a belief, which I didn’t know I held, that if I put everyone and everything in order, no one else would die. Though these vigorous efforts to direct, classify, and manage were always valued and lauded by others, I’ve recently come to understand them as unthinking ways of dealing with anxiety. Even my compulsion to write probably comes from the same desperate need to order and organize as a way of asserting control over an uncontrollable, stressful, and ever-changing world. Perhaps as the crypt’s architects carefully assembled the bones of their departed brothers into archways and chandeliers, they felt this same impulse, to create order in the face of death.

How much ordering is too much? The thousands of tibiae and fibulae, skulls and scapulae, fingerbones and backbones, all removed from their bodies of origin, scrupulously cleaned, collected, and organized by type, remind me of certain World War II concentration camp photographs: mountainous piles of eyeglasses, shoes, brushes, pots and pans, human hair and prosthetic limbs, all removed from their bodies of origin, carefully sorted and categorized. As if all this purposeful activity, the effort and time spent collecting and organizing these confiscated objects, could somehow create order out of the chaos of mass extermination, and with that order make sense of senseless cruelty.

Once we exit the crypt, the tour stops at the gift shop, which sells postcards of the chapels, as well as a shockingly overpriced coffee-table book brimming with lavish, grisly photographs. At last we reach the sanctuary of the basilica, where we sit in a dim, expectant silence, half-stunned after our unexpected detour. The singers enter quietly, dressed in robes and processing up the aisles like the friars must have, ages ago. When the music starts, haunting melodic strands woven through with longing and reverence and mystery, the austere splendor of the voices, that ephemeral beauty of the breath in time, singing our finitude, both pains and uplifts me. And pierces me, yes, down to my very bones.

Decatur, Georgia