Can the Tooth Fairy Pay in Hong Kong Dollars?

We met for the first time at a modern Chinese restaurant in the heart of Causeway Bay, the name of which is nowhere near as memorable as the fact that they serve xiao long bao in eight different flavors and colors. The classic xiao long bao with pork filling is available all over the world, and this restaurant put a contemporary spin on them with luffa gourd, foie gras, black truffle, cheese, crab roe, garlic, and Szechuan peppercorn flavors. I was sure your mommy and daddy would love them: all of my close friends from America love warm, down-to-earth dishes like xiao long bao, dumplings, and noodles in soup. Your mother is Cantonese, so she obviously knows about xiao long bao; your father, who is American, also likes XLB (as English speakers often call it). Your auntie Jennifer was also there: she translates Hong Kong literature from Chinese into English and steams mini XLB for breakfast at home in America. My Hong Kong friend Louise, who had just been in San Francisco giving talks with your mommy and Auntie Jennifer, chose this restaurant for our dinner when you all came to Hong Kong.

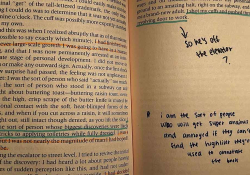

Before the XLB arrived, you were crawling on the bench next to your mom, pushing on one of your tiny loose front teeth with one of your tiny fingertips. With an air of excitement, you told us it was about to fall out. Your words made me realize that I had already left all my milk teeth far behind me. I’m over two decades older than the six-year-old you, and all of my teeth are now permanent. Any teeth falling out would be a painful and expensive accident for me now, or a cruel trick Fate played on me by giving me wisdom teeth so crooked they required surgical extraction. Of course, I won’t tell you now that adults would grow these things called wisdom teeth, and that if one were as unlucky as I was, one might need to lie in the chair of the oral surgeon for an hour while they cut up one’s wisdom teeth into pieces for careful extraction from the lower jaw. These scary things that you don’t have to face till much later in life needn’t have been brought up at our first meeting, especially not while waiting for our colorful XLB.

I was going to tell you in English that I wasn’t scared or in pain when my milk teeth fell out: I once lost one of the last ones when eating daan tat on a picnic. When it happened, I briefly checked the new hole in my gums with a mirror, rinsed my mouth with a sip of water, and finished my daan tat so I could continue playing with my mommy and daddy and aunties and uncles and playmates of my age. I don’t even remember seeing any blood. Yet you seemed so unfazed about your tooth being loose that you repeatedly played with it as if it were a button tooth in the Crocodile Dentist game, so I guess you didn’t need my story to feel better about changing teeth. Your mommy and us aunties repeatedly told you to stop playing with it, or else the new teeth to come after it fell out would come up all crooked. I actually didn’t know if that was a medical fact or just a cautionary tale mothers and aunties tell children, but not messing with your teeth is always sound advice.

I was shocked to learn that the Tooth Fairy came with your family from America to Hong Kong and took the tooth you lost within our city boundaries in exchange for Hong Kong dollars.

You made a face at us, picked up your mom’s phone to create animations of animals running in jungles or on beaches with a coding software for children, and stopped paying attention to us grown-up buzzkills. We started sharing stories about what our parents told us when our milk teeth fell out. Your mom and Louise were told to throw their milk teeth straight upward into the air, so that the new teeth would grow back nice and straight (unlike my wisdom teeth that grew sideways like the reclining Buddha or a very lazy seal). Your auntie Jennifer told us that when you were at a party in Tai Mei Tuk last night, your mom helped you shed a milk tooth that was hanging by a thread; this morning when you woke up in your hotel room in Hung Hom, you found a US dollar bill and a Hong Kong ten-dollar bill under your pillow. I was shocked to learn that the Tooth Fairy came with your family from America to Hong Kong and took the tooth you lost within our city boundaries in exchange for Hong Kong dollars. Of course, as an adult who often bursts my own bubbles, I know that the money under your pillow came from your parents instead of a Tooth Fairy without a fixed gender, image, or exchange rate from tooth to cash. But can the Tooth Fairy work their magic under the roof of a Hong Kong parent, not just that of European or American parents?

I had heard of the legend of the Tooth Fairy as a child too, probably from TV shows imported from the English-speaking world, English-language children’s books in public libraries, or stories told by our native English teachers. When I told my very stereotypical Chinese mother that foreigners believed in placing lost teeth under pillows for the Tooth Fairy to replace with cash the next morning, she rolled her eyes at me. I knew right then the Tooth Fairy would not visit this Hong Kong household, and I never bothered placing my lost teeth under the pillow to test if my very practical mother would make a fairy tale come true for me because of a story I told her. I never got any money for losing my milk teeth, just like how I never saw any of the red packet money my mom said she was saving up for me after taking them away after Chinese New Year. Maybe the Hong Kong dollars and Renminbi gifted to me by family and friends had turned into funding for the braces my mother got for me after all my teeth became permanent, in a different sort of exchange between cash and teeth that only happens in Chinese families. Your mom showed me a picture of the letter you wrote to the Tooth Fairy, written in crayon; the tooth you were playing with would soon be claimed by the Tooth Fairy too. I realized that I had never fully believed in the Tooth Fairy, just like any Santa Clauses that appeared in Hong Kong.

I learned from American sitcoms that it is extremely rude to tell other people’s children that Santa isn’t real.

Oh, don’t worry, I definitely wouldn’t talk about whether Santa is real or not in front of you. I learned from American sitcoms that it is extremely rude to tell other people’s children that Santa isn’t real. It should be those closest to you who break the news, and not like Chandler from Friends telling a young boy’s parents that “you should have a sign out there or whisper it to people when they come in that Owen doesn’t know he’s adopted, and he also thinks Santa is real” while Owen was standing right there. There are of course Santa Clauses in Hong Kong. It’s just that they are really, really fake: white-collar workers’ black leather shoes peeking out from underneath black boot covers, East Asian black hair peeking out from underneath white beards and red Santa hats, one of the male teachers never being in the same room as Santa at the same time during the Christmas service.

The Santa played by my parents was really fake too. Every Boxing Day morning, my siblings and I would find the tomato-flavored crisps that were available at the nearby supermarket, and my parents would pretend to be surprised at what Santa got us. As children, our parents had total control over what we ate, which meant healthy snacks like fruits, whole-grain bread, cheese slices, digestive biscuits, and Horlicks and Ribena instead of candies, soda, crisps, and traditional preserved fruits high in sodium and preservatives. Treats like juice, chocolates, and ice cream only showed up on special occasions like birthdays and holidays. If our parents were willing to get us crisps once a year in Santa’s name and make him real for one day, why should we harsh the buzz? Many years later, my younger brother and I (all grown up and fully capable of buying our own crisps) brought up to our mother that we knew they were Santa all along. My mom rolled her eyes as if to say, obviously it was us, you didn’t actually believe in Santa, right?

If our parents were willing to get us crisps once a year in Santa’s name and make him real for one day, why should we harsh the buzz?

Of course not. We hung up Christmas stockings for a few years only, because Santa retired from our household when our dad started gifting each of us a box of Ferrero Rocher after Christmas dinner. The kind of American Christmas with presents under the Christmas tree in the living room and a roasted turkey for Christmas dinner only happened once in our home when my mom suddenly decided she wanted to give it a try, and that was already a lot more than many born-and-bred Hong Kong Chinese households had. There are always Christmas trees in shopping malls, lift lobbies, churches, schools, Statue Square in Central, and many other places around Hong Kong, but people with Christmas trees in their own homes are mostly expats and people with a big enough apartment and enthusiasm about celebrating this particular holiday. The Christmas cards I exchanged with classmates featured images of snow and Santa’s sleigh, stuffed stockings hung on top of the roaring fireplace, Christmas trees in the living room adorned with baubles and candy canes: they all seemed to be depicting scenes from Europe or America far removed from my city, a place where it doesn’t snow and with enough densely packed skyscrapers for all flying reindeer to break their necks on. Even if Santa were to come to Hong Kong from Finland, where would he land his sleigh when our rooftops are filled with drying laundry, and how would he enter houses without any chimneys in sight?

Red and green and yellow and black and orange and brown and gray and white XLB arrived, like a string of colorful Christmas lights coiled up in the bamboo steamer basket. Your mom looked at the XLB index card provided by the restaurant to single out a few flavors that didn’t contain ingredients you are allergic to and asked if you wanted to try any of them. You said no to all of them. She started explaining to us that you had always been a picky eater when you suddenly decided you wanted the green luffa gourd XLB. She carefully picked up the fragile soup-filled dumpling with her chopsticks and moved it to your plate. You took one bite before returning to your mobile phone game and showing off the animation you made, leaving the XLB on the plate to get cold. Your mom was so accepting of your food preferences: at the very beginning of dinner, she ordered you steamed dumplings, spring rolls, and a cold bottled water to make sure that safe things you liked to eat were on the table while you considered and rejected all the novel dishes she recommended. She only insisted that you eat enough at dinner or else you wouldn’t get the wagashi from Tokyo you kept asking for as dessert. Watching the two of you, I wondered if mothers raising children in America tended to be like your mom when it comes to children’s food preferences, instead of stereotypical Chinese moms that consider picky eaters as unruly and in need of discipline? I think your mom shows her love for you by going along with what you like, letting you venture out of your comfort zone at your own pace while making sure there are always options for you to fall back on.

Every family has their own Santa Claus, and every parent has their own love language.

My mom showed her love for us by making sure all the food she provided was healthy in her eyes, and our individual preferences were not a key factor when she was most concerned about food safety and nutrition. Every family has their own Santa Claus, and every parent has their own love language. I read online that most children will learn the truth about gift-bearing imaginary figures like Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, and the Easter Bunny between the ages of five and seven. It is one of the markers of growth, just like developments in coordination, logic, language, social relations, and emotions. Toward the end of dinner, you danced and sang “Little bunny, oh-so-white / Two ears standing straight upright! / Loves eating carrots, loves eating greens / Hop hop, jump jump, such a cute scene!” in Mandarin. My dear little girl, could we wait till at least after your little loose tooth falls out before you learn about the truth that we adults all had to learn? When that happens, maybe I will ask your mommy to let you read this monologue I wrote for you, and let you see that your parents loved you so much that they were willing to play along with a fantastic story, until the day you stopped believing in them.

Hong Kong

Author’s note: This essay was written in response to a prompt I received in preparation for events during the fall residency of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa in 2023: “Which dreams and myths do you hold of America? And do you also have fears? What are your hopes for the American story, and what role, if any, do you play in it?” Special thanks to Jennifer Feeley for her editing of this first attempt of my writing in English, and her masterful translation of the bunny song, which goes like this in Mandarin: 小白兔 / 白又白 / 兩隻耳朵豎起來 / 愛吃蘿蔔愛吃菜 / 蹦蹦跳跳真可愛.

Editorial note: WLT’s 2019 Hong Kong city issue, guest-edited by Tammy Lai-Ming Ho, features a number of food-related pieces.