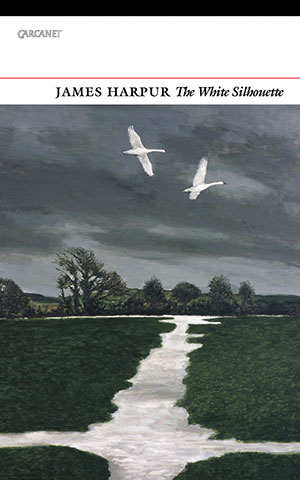

The White Silhouette by James Harpur

Manchester, United Kingdom. Carcanet Press. 2018. 96 pages.

Manchester, United Kingdom. Carcanet Press. 2018. 96 pages.

James Harpur’s The White Silhouette is a beautiful collection of poetry in three parts. “The White Silhouette” is a tour of faith and history. “Kells” imagines a conversation with the various artisans of that famous illuminated text. The last section, “Leaves,” blends classical references with memories of family, school, friendships, and loss. The book’s total effect is both complex and meditative.

“The Journey East: Winter 2010” is a pilgrimage across the beautiful landscape of Ireland’s southern coast. In the regular pacing of couplets, Harpur unfolds a terrain made strange by rare snowfall, transformed into “Iceland? Greenland?” before returning to familiar place names: Cork, Dungarvan, Waterford, and on to where the ferry leaves for Wales.

The multipart, ekphrastic series “Graven Images” is part of this pilgrimage. Each poem within the series describes holy works of art ravaged by sectarian strife. Harpur’s craft here reflects the subject, as in “Cross,” depicting a tortured cross in such a way as to suggest a second crucifixion. The poem further enacts itself as a concrete, or shaped, poem.

Following this series, Harpur places “Headless Angels.” This poem, about statues in a Galway church vandalized by Cromwell’s soldiers, not only seems to summarize the loss described more objectively in “Graven Images” but also delves into the minds of those vandals, wondering whether they were shamed by the gaze of the statues they destroyed, and if they “conceal[ed] in the priest holes of their minds / a grain / of imagination.”

Throughout the collection, Harpur’s craft is both beautiful and subtle. It is difficult to find an adequate example of the assonances or partial rhymes that seem to drive the poems’ melodies, but one example from “Goldsmith” in “Kells” shows Harpur’s wordplay: “Do not depict the likeness of things / but the Ideas from which they arise – / not a rose, but Rose, in which / a rose will be the essence / of all roses.” The advice given here in an imagined dialogue between a contemporary poet and this ancient scribe is perhaps the best summary of Harpur’s achievement in this worthwhile collection of poetry.

Greg Brown

Mercyhurst University