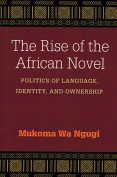

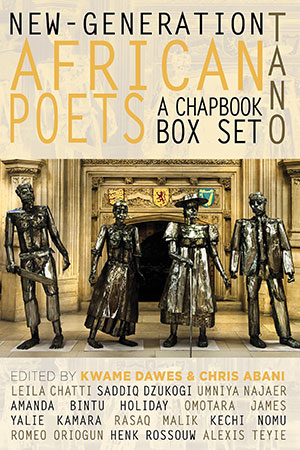

New-Generation African Poets: Tano

New York. Akashic Books. 2018. 350 pages.

New York. Akashic Books. 2018. 350 pages.

The New-Generation African Poets book series is an ambitious program to publish together poets who have yet to publish full-length books. The 2018 edition, Tano, offers eleven chapbooks by poets from across the African continent and diaspora, accompanied by an “introduction in two movements” by co-editors Chris Abani and Kwame Dawes. Each volume also includes a foreword by a well-known poet or poetry scholar.

The poets included hail from Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Kenya, Tunisia, Sudan, and South Africa, with ties to the UK, the US, the Caribbean, and Germany. The greater number are from, or have ties to, the continent’s most populous nation, Nigeria. For readers accustomed to historically male-dominated African literatures, women, in this instance, outnumber men seven to four. Dawes describes these poets as navigating “multiple aesthetics of region, nation, continent, and the wider world,” and Abani writes of the series’ consistent publication of experimental poetry. He remarks, in particular, on the “aesthetic safe space” the African Poetry Book Fund provides for poets “whose sexuality might not be accepted” within their religious/cultural communities. The breadth and variety of the work is impressive. Although impossible to discuss each chapbook in the space allotted here, two are especially compelling.

No Home in This Land, by Rasaq Malik, opens with “Dedication,” which serves as both a literal dedication of the volume to peoples, families, and individuals stunned into death by internal conflict, assassination, execution, and murder; and an extended elegy that reveals the unending loss, attendant numbness, and nightmarish terror that make up the daily lives of those who mourn. With near-epic command of language and time, Malik weaves Syria’s civil war, Boko Haram’s ongoing jihad, and the 1995 state execution of Niger Delta environmental activist-poet Ken Saro-Wiwa into a taut litany that underscores the shared experiences and fates of nations wracked by unceasing bloodshed. “For the woman cupping the candlelight that flickers in a room / in Aleppo, for her children who curl their bodies in bed . . . stunned / faces of people recovering from . . . a blast in Maiduguri. . . . / For Syria . . . / the forgotten names of dead soldiers. // For Ken Saro-Wiwa . . . a sacrifice / at the Nigerian gallows.” In the poems that follow, he creates an all-seeing narrator who trains a candid lens on the lived experience of mass mourning and individual grief accompanying the now decade-long Boko Haram atrocities. No mere witness, however, could render such lines as “A woman sieves a pile of corpses” or “My grandfather dies with our country’s name on his lips, / my grandmother said, do not bury me in this land when I die.” This speaker is weary and wary of his homeland become dirge, fellow citizens expert in “the art of grief whenever people become rubble.” At his most intensely observant, Malik conjures Gwendolyn Brooks’s “One Wants a Teller in a Time Like This.” His is a teller on intimate terms with violent death who simultaneously dares, somehow, to imagine an ordinary future when children live to laugh and play, outdoors and unslaughtered.

The Art Poems, by Amanda Bintu Holiday, is remarkable for its easy command of visual imagery. A working visual artist since 1980, Holiday also directed films and worked in educational television before turning to poetry. Among the artworks her poems address are such recognizable tableaux as Gauguin’s primitivist Loss of Virginity; Bill Traylor’s Untitled fabulist depiction of a large man, cane in hand, balancing on his head a great blue-colored earthen pot atop which sits a dog; and Picasso’s Girl Helping a Minotaur. Even if we had never seen any of these works, however, we would have no choice but to be awed by Holiday’s graphic precision and deft use of ironic humor, depth, and verve. Without Paula Rego’s untitled aquatint, for example, we respond to the tired maxim of having some cross or other to bear and snicker appropriately at a character determined to “ditch the blunted beam / in some passing alley or well // where God won’t look.”

All the World Is Now Richer, and other works by Kalabari-born sculptor Sokari Douglas Camp, grace the covers of each chapbook and every side of the box containing the whole. Named for the sacred grove from which the Tano River runs some 250 miles from its head at the Ghana–Côte d’Ivoire border before emptying into the Atlantic, APBF’s Tano is exquisitely composed and designed. This is a boxed set to be collected—and coveted.

Brenda Marie Osbey

New Orleans, Louisiana