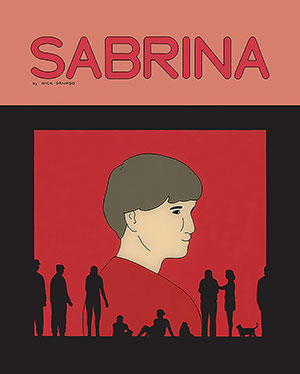

Sabrina by Nick Drnaso

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2018. 203 pages.

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2018. 203 pages.

It’s no secret that graphic novels have come of age in the twenty-first century in the sense that they are now taken seriously by readers and reviewers. No longer do we point to Maus and move on. In the case of Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, the first graphic novel to make the longlist for a major literary prize, the Man Booker, the power of the graphic novel to dissect and examine our cultural moment is indisputable.

The plotline is simple: a woman we meet briefly disappears and eventually is revealed as having been murdered. But it is not the suspense of the plot that holds us, nor is it the minimalist drawings. There are no artistic pyrotechnics here, and Drnaso never varies from a fairly routine grid design. But he clearly demonstrates that quotidian life in post–9/11 America is anything but simple.

Sabrina disappears in Chicago after some brief scenes with her sister Sandra. Her boyfriend, Teddy, goes to Colorado to stay with an old high school friend, Calvin Stroebel, a programmer for the air force. They were never close friends, but they are both going through crises—the loss of a girlfriend and the end of a marriage. In many ways, they are each the definition of isolation, even though neither they nor we know what is going through their minds. Cal is required to fill out periodic DOD mental-health surveys requiring responses that range from one to five and end with a yes-or-no question about whether he wants to see a clinical psychologist. The minimalism of the survey mirrors his clueless taciturnity. Teddy is a basket case and barely communicates except via a loud scream after occasional nightmares.

The reluctance to examine feelings is nothing new in literature, but Drnaso’s genius is in depicting how one incident and its aftermath, Sabrina’s murder and the way the information is revealed and disseminated via the internet, excites a portion of the population to reach out to these men. Conspiracy theorists, haters, skeptics, indeed pretty much anyone who has access to a computer, weighs in, attacks, surmises, etc.

Life in the novel is mediated and interpreted through electronic devices—from televised commemoration of the sixteenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, to Cal’s skyping with his daughter, to anonymous, threatening emails, to a disembodied conspiracy theorist’s voice that seems omnipresent on the radio. The Albert Douglas radio show will sound very familiar to anyone who has ever heard Alex Jones or his fictional counterparts in shows like Homeland.

But the strength of this work is not in its similarity to reality but rather in the way its depiction of the minutiae of our lives and the accretion of the voices that worm their way inside our and the characters’ heads grows more and more frightening. By the end of this novel, you realize the murder is incidental to the chilling indictment at the heart of the narrative—that of what our society has become.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City