How Is American Poetry Reviewed in China?

We asked Ming Di to take a look at how US poets have been reviewed in China for the past decade. The results provide a window into what reviewers are seeing in US poets’ work and which poets are most popular in China. (Spoiler alert: Ocean Vuong is as popular there as he is here.)

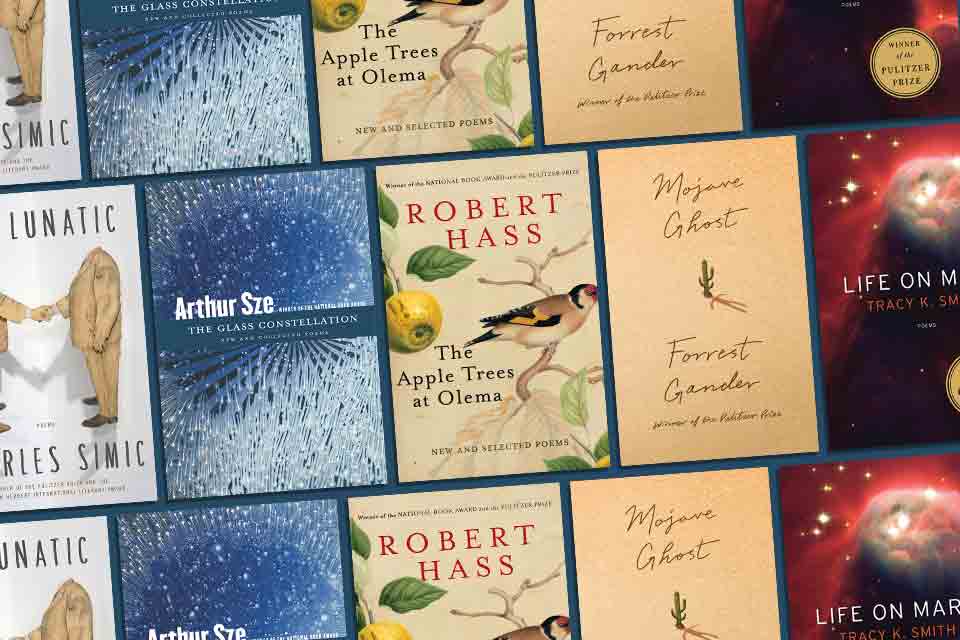

One might be surprised to see how some poets in China admire Forrest Gander while others loudly praise Charles Bukowski. Literary reviews have been as divided as poetry circles since two major poetry camps emerged from the infamous Panfeng Debate in 1999. Various groups of “Intellectual Writing” poets love the delicate texture of Gander’s poems, but the Spoken Language poets enjoy Bukowski’s drunken rants, both dreamlike and enchanting in their Chinese translations. While every Nobel and Pulitzer laureate has been translated and reviewed in China, a country of more than twenty thousand published poets with a big book market and an insatiable thirst for foreign literature, Gander was already a beloved author in China before he won the Pulitzer in 2019 and was invited to China on numerous occasions before and after 2019.

Literary reviews have been as divided as poetry circles since the two major poetry camps emerged from the infamous Panfeng Debate in 1999.

Song Lin, in his review of Be With (translated by Dong Li), compares Gander’s intertwining of love and death to the Taoist concept of “materialization,” which refers to the boundary between self and object leading to a state of unity and oneness, a spiritual experience where the individual transcends his self-consciousness and becomes one with the other. As a result, the transformation of love and life-death becomes the “entry” and “exit” of life in a trance (Shanghai Culture). Zhai Yongming, in her foreword to the Chinese edition of Mojave Ghost / Knot (also translated by Dong Li), compares Gander’s ecological underpinnings with the Chinese concept of “harmony between man and nature” and its internal connection with Gander’s poetry.

Charles Bukowski never visited China, nor was he highly regarded in the mainstream literary world in China, but he has been hailed in recent years as a countercultural and antimainstream hero and “great loser” among the nonacademic and noninstitutionalized Spoken Language poets. Shen Haobo, head of Xiron Books, one of the biggest independent publishers in China, has promoted Bukowski through publication of his poems, novels, and essays. Yi Sha has translated two collections of his poems. Yu Jian wrote two poems as book reviews, often quoted by other poets, and in one of them describes Bukowski as “amazingly pure / unafraid of being shallow / and most boringly profound.” All of them—Yu Jian, Yi Sha, and Shen Haobo—are prominent names from the Panfeng Debate of 1999 on the side of the Popular Poets (i.e., Poets of the People), as opposed to the elite poets of “Intellectual Writing” where Xi Chuan and Ouyang Jianghe, along with many others, are categorized. But the division has faded over time. Yi Sha has become the cheerleader of Post–Spoken Language Poets, and Shen Haobo has been promoting Lower Body Poetry. Yi Sha wrote one of his most passionate poems as a review of Bukowski and contrasted him to Allen Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, Robert Frost, Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Robert Bly, Czesław Miłosz, and Joseph Brodsky, ending the poem like this: “unmoved, untouched, unaffected (by their success or fame or drinking) / he drinks his own drinking, fucks his own fucking till he can’t fuck anymore / he lives his own fucking life till he can’t move anymore / and dies his own fucking death when it’s his time to die.”

But some poets who were introduced to China much earlier, such as Gary Snyder, have somehow enjoyed equal admiration from both sides and even from all corners of China—namely, from academia, government institutions, off-mainstream outlaws, and general readers. In a review of two Chinese editions of selected poems by Gary Snyder, translated by Xi Chuan in 2017 and by Liu Xiangyang in 2019, Yu Qing compares the two different versions and examines the realm of self and the Buddhist realm of no self in Snyder’s poetry. He finds that Xi Chuan frequently uses elegant language with a classical prosody while Liu Xiangyang tends to use everyday conversational language, resulting in different outcomes produced by a poet-translator versus a translator, implying not only the creativity of a poet-translator but also the insightful understanding of Snyder’s nature poems, which actually contain social issues like the poetry of Du Fu from the Tang dynasty. This is one of the few reviews that pays attention to the translation process in addition to the poems per se. His comments are winding and subtle, just pointing out the differences of the two approaches to translation without saying which is superior. Through his step-by-step analysis of the translations compared with the original English version, readers can get a better understanding and appreciation of the linguistic and stylistic beauty as well as the social and ecological concerns in Snyder’s poems.

In reviewing The Glass Constellation, by Arthur Sze and translated by Shi Chunbo, Lan Lan writes that Sze is a poet with a strong sense of style, breaking apart the usual form of poetry, which might be related to his desire to obtain a full sense of the universe (NBRW). Yuan Yongping, reviewing for the Phoenix Weekly, finds Sze’s poetry a salad of the physics of cosmology, the mathematics of nature, classical Chinese poetics, and American modernist imagery. Both reviewers are female poets (so is the translator) without a typical critical background, unbound by theories of literary criticism in China, which is heavily influenced by Liu Xie’s The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons (501–502 ce), a somewhat Buddhist or dualistic approach to literature further influenced by the I Ching (ca. 3,000 bce).

Reviews written in Chinese but based on reading the English versions directly can also be found. Wen Jingtian regards Jane Hirshfield highly as a soul poet. To him, her poetry reveals the enlightenment from studying Zen for many years and reflects the influence of the Japanese court poetry that she translated. Her poems flow, leading to metaphysical mystery, but her words never overflow. “She doesn’t rely on language, as language has its boundaries when defining the world of existence, but Zen meditation has no boundaries. The kernel of her poetry lies in the awakening heart” (Poetry Canon).

Luo Lianggong and Liu Ninuan review Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars, taking “dark matter” as the key to understanding this collection of intricate poems. Dark matter is not only used as a strategy to write about the sci-fi world but also a metaphor for the decline of American society. The term “dark matter” only appears twice in the entire book, but they think it is a crucial concept and underlying theme throughout the book. Dark matter in a way functions as a glass reflecting reality (Yangtze River Academic).

Luo Lianggong and Liu Ninuan review Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars, taking “dark matter” as the key to understanding this collection of intricate poems.

Many other poets—such as Juan Felipe Herrera, Sharon Olds, C. D. Wright, Rita Dove, Jean Valentine, Simon J. Ortiz, John Yau, Gregory Pardlo, Kevin Young, Tony Barnstone, and Terrance Hayes—have been invited to China, reviewed, and/or interviewed. Interviews are book reviews in depth and provide readers an opportunity to listen to the authors directly. In a recent long interview with Jane Hirshfield (River Yan Journal, 11/2024), Ma Yongbo asked many questions, such as: “What inspired you to write poetry? Do you belong to any poetry school? If not, do you have your own concept of poetry different from other poets? Is your poetry related to feminism? As a Zen practitioner, what is the relationship between belief and poetry and how is it reflected in your poetry? American poets, starting with Whitman and Williams, have been trying to establish a local poetics different from the European tradition. What role have you played in the construction of American poetics? What do you think of experimental poetry such as L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E and the poetry of Jerome Rothenberg?” Hirshfield provided brilliant answers along with examples of her poems. Ma Yongbo asked another interesting question: “Buddhism teaches us to get rid of the obsession of self. Does this impose a conflict with the complex experience of contemporary life? After all, poetry comes from the self. How do you deal with this paradox of transcending the self and going deep into the self?” Again, Hirshfield explained patiently with examples of her poems. Both like and more than a review, this question reminds readers to go deeper into her poetry and is probably also helpful to readers of her original poetry in English.

Interviews are book reviews in depth and provide readers an opportunity to listen to the authors directly.

Feng Yi, a new translator of Charles Bernstein (a frequent guest in China), explores Bernstein’s echopoetics in a 2024 article. The illogical fragments, multilayered rhetorical superposition, parodies of classics, and juxtaposition of postmodern and classical elements in Bernstein’s poetry reflect not only Western tradition such as Adorno’s negative dialectics and Benjamin’s philosophy of language but also another profound philosophy, the Eastern fusion of Zen Buddhism and Taoism. In her opinion, the power of ethereal beauty in Bernstein’s poems can only be appreciated through the perspective of Zen Taoism and in the context of reversal of nihilism and existentialism (Foreign Literature and Arts Review).

In a review of Adam’s Garden of Apples, Yuan Yang’s translation of Robert Hass’s The Apple Trees at Olema, Liao Lingpeng takes note of the Eastern philosophical thinking and aesthetics in Hass’s poetry. Hass emphasizes sound and light and the shadow of landscapes, consistent with the spiritual temperament of Chinese classical poetry. Some of his poems resonate with the Book of Songs; others echo the Yuefu from the Han Dynasty (China’s Writers Web). Jiao Youping writes about how Hass is influenced by Miłosz but also departs from him, analyzing three aspects of his poems: ecological, antiwar, and questioning monotheism (Jiangsu Ocean University Journal).

Louise Glück has received mixed reviews. Several prominent poets in China made comments on WeChat (a social platform similar to Facebook) when hearing the Nobel announcement, saying that she was a good poet but not a great poet. But Ying Zhi found that these poets were misled by the Chinese translations. His own first impression was that “there is not a huge gap between Glück and some of the best women poets in China. She is not outstanding among the Nobel laureates. What makes her different from Chinese women poets is her control of passion. She is lyrical with delicate and specific details.” Moreover, he writes, “it’s relatively easy to translate her poems through a translation app, and it’s precisely for this reason that the published translations of her work all lack attention to the details and subtlety in her work.” He went on, saying,

After reading several books, I have noticed that the translations presented the opposite of what seem to be the implied meanings. I had to personally translate some of her poems, and in doing so, I was immediately struck by how plump and juicy her lines were and how complete her poems were. What is poetry, then? It is an encounter with another soul in the deepest possible depths, and you are inspired immediately, your imagination activated through the encounter. She seems to be so good at capturing contradictions and finding a balance between two oppositions. Her poems are sensual and simultaneously intellectual. While Chinese women poets are focused on personal pain, she is much beyond that, and, surprisingly, she has an unusual sense of humor. (Poetry Review Blog by Ying Zhi)

Although poets who have won major awards receive more attention in China, less recognized poets are often discovered as well. Richard Brautigan became popular among young readers in 2016. In a recent review by Liubai Dushi, Brautigan is seen as an “alien,” with unimaginable imagination and unconstrained constraints, but also “simple, easy to understand, yet cold and sometimes humorous.” Liubai writes that “his blood runs in the veins of Chinese literature” (Liubai Dushi Blog).

Brautigan’s poetry is translated by two young poets, Xiao Shui and Chen Xi. (Xiao Shui also co-translated Jack Spicer, and with this first-ever translation of Jack Spicer in Chinese that just came out, he wanted to make Chinese poets explore new ways of writing and a new architecturing of poems.) Many young poets also like Charles Simic, on the other end of the spectrum from Brautigan. Li Suo comments on The Crazy (original titled The Lunatic, translated by Li Hui, 2022) that Simic’s poems are “cool and playful, wise and humorous, plumbing the depth of human emotions in simple language.” Du Peng considers Simic the poet who completely changed his opinion on the necessity of using one’s mother tongue in poetry writing and found that “the incompleteness and alienation from the memory (of his mother tongue) made Simic highly recognizable” (Book Review Weekly of the New Beijing Daily).

Ilya Kaminsky has been the most talked-about young poet in China since 2010. A more recent idol for young Chinese poets is Ocean Vuong.

Ilya Kaminsky has been the most talked-about young poet in China since 2010. A more recent idol for young Chinese poets is Ocean Vuong (translated by He Yingyi). Numerous short reviews and comments have appeared on the internet: “profoundly sad,” “unbelievably touching,” “so unusual,” “so extraordinary.” His life story completely caught the youth off guard. Poetry from Vietnam, which was largely ignored until the twenty-first century, has thus entered the field of world poetry in China through an immigrant poet from the US, totally different from T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, or any of the other familiar names that have captured the imagination of Chinese poets for a century. Finally, people have stopped talking about the reciprocal and circular influences—American imagist poets were influenced by Chinese classical poets and in turn influenced the Chinese New Poetry that started in the early twentieth century—and have stopped comparing the new generation of American poets with Du Fu or Wang Wei.

Los Angeles