Traversing the Human/Simian Divide: A Conversation with Prateek Vats

Eeb Allay Ooo! (2019), directed by Prateek Vats, is part of an emergent oeuvre of multispecies cinema from India. Screened at the Panorama section of the 70th Berlin International Film Festival and a winner of the Golden Gateway Award at the Mumbai Film Festival, Eeb Allay Ooo! focuses on the lives and experiences of “monkey repellers”—men employed to chase rhesus macaques either via vocalization (hence the onomatopoeic “eeb allay ooo”) or dressed as langurs—in New Delhi. The film is a probing critique of urban precarity and a haunting exploration of multispecies cohabitation in the neoliberal city. Its narrative core is the friendship that develops between the lead character, Anjani (Shardul Bharadwaj), and the more experienced monkey repeller Mahender (Mahender Nath). An unanticipated tragedy sunders this friendship. (Disclaimer: This interview reveals crucial plot details about the film.) At the same time, the film also meticulously tracks simian movements and existence in the city. The interspecies relationships between humans and simians are often laden with violence but also reveal moments of fraternity and care. This ambivalent representation of multispecies relationalities shows the fluid dynamics of human and animal life in urban spaces and makes Eeb Allay Ooo! a powerful representation of Delhi in the Anthropocene.

Amit Baishya: Can you tell us about the way you conceptualized the film and the ideas behind it? What were some of the specific challenges that you faced?

Prateek Vats: India, the biggest democracy in the world, employs exploitative contractual labor to secure the highest offices of the land from the nuisance created by a “holy” animal. The inherent absurdity of this situation is what drew me to make this film. For me, it sums up the prevalent situation in India—a nation state propped up on the dehumanized labor of its citizens. Eeb Allay Ooo! is a response to the world around us—a world that is hard to make sense of, a world where being a monkey is far more liberating than being human.

There were two main challenges: (a) shooting a fiction film with untrained monkeys in their natural habitat, and (b) shooting in one of the most “high security” areas in the country (near the Parliament House and Rashtrapati Bhavan) where we had little control over permissions and hence schedules. This was a nightmare for shooting a fictional narrative.

Baishya: The film begins with a montage of facial close-ups of people vocalizing “eeb allay ooo” and ends with the Ramleela celebration where the protagonist, Anjani, looks straight at the camera, smiling unsettlingly with the mask covering and revealing his face. Can you comment on the significance of the role of repetition and the counterpointing of visual motifs in the film?

Vats: The film in many ways is about people who are systematically made invisible by the middle-class gaze. It was important for us to register faces and individuals rarely seen in our films. Every face, to us, became a window into a life unseen, whose story remained untold. It was important to confront their gaze and gauge how our own gaze changes through the course of the film.

Every face, to us, became a window into a life unseen, whose story remained untold.

Repetitions are used throughout the film, both in the overall structure and in scenewriting. It helped us enhance humor as well. We wanted the film to be a satire that borders on outright farce at times. Cutouts, the recorder, the gun, notes, and many other small things keep repeating in the film, but the emotions they evoke vary. It was a formal decision for us—which props to use and how to use them so that the corresponding emotion was appropriate.

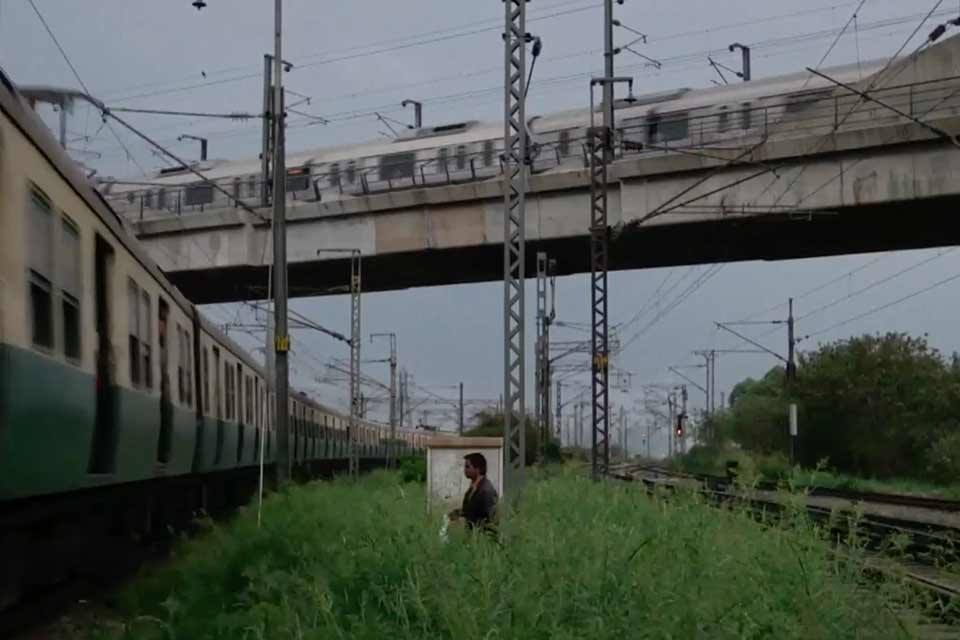

Baishya: One of the most striking visual repetitions in the film is the shots of people within the air-conditioned bubble of the Delhi metro counterpointed with the shots of the protagonist crossing railway lines to get to the chawl. The railway lines seem to function as a spatial marker for segregation in the city. Can you elaborate on that?

The tracks became not just a marker of spatial segregation but a psychological one as well.

Vats: We wanted to evoke a city where workers are needed but unwanted. This idea germinated from how the city handled working-class neighborhoods while preparing for the Commonwealth Games in 2010. Large steel walls were erected around them so as not to disturb the “visual aesthetic” of the city we wanted to present to the world. It was policy-level dehumanization of a population by a state. The practice continues to this day for events like the G20 summit.

Throughout the film, the railway line becomes a sort of a border, beyond which our primary characters live, far away from the swanky “center” of the nation’s capital. For us, the tracks became not just a marker of spatial segregation but a psychological one as well.

Baishya: The film begins with a dark screen with “eeb allay ooo” resonating in the sonic background before we see a montage of faces. Can you comment on the sonic aspects of the film, both the use of everyday sounds and the repetition of human and animal vocality in the film?

Vats: The entire idea of the film is based on sound. Hence the onomatopoeic title. It forms the central motif in a film where the protagonist must literally become a monkey to survive in his world. The combination of the human and simian voices was a perfect base for us to leap into a satire where becoming a monkey is more liberating than remaining human.

Overall, the sound elevates the film from a physical to a psychological space. The movement from objective to a much more subjective soundscape helps in creating emotional proximity to our characters and the worlds they inhabit.

Baishya: The digital recorder plays an important role in the film, especially in the moving sequence at the end when Anjani listens to the now-dead Mahender’s vocalizations. Can you tell us more about the role of the recorder in the film and why it appears at crucial moments?

Vats: The recorder is one of the many props that we use in the film to take the emotional narrative forward. When using props with that intention, we have to create an arc for them as well. The recorder helps keep Mahender’s presence alive even after he is gone. It stores his memory as his voice, the only utilitarian value that he has for the system.

After Mahender’s death, the film moves into a much more psychological space for Anjani. Mahender’s disembodied sound is used as a pivot for this movement. The recorder itself becomes important—from an innocuous-looking prop to aid Anjani’s work to a fleeting container of his friend’s memory. It disappears without explanation, much like its arrival in the film.

Baishya: While the railway tracks function as a visual metaphor for the spatial segregation of the different classes in the city, there are numerous interpersonal encounters that also show the fluid verticality of power and powerlessness: Anjani’s boss threatening him and being threatened by the bureaucrat later, the encounters with the doctor, the middle-class man feeding bananas who threatens Anjani, etc. I was rewatching the film recently and was struck by how it plots an anthropology of power relations among classes in the city. Could you comment on that?

Vats: New Delhi is a power center, and the power structure is highly graded and hierarchical: someone is always above you as well as below you. Much like the graded caste system that defines societal structures in India, this graded structure of power ensures that the exploitative systems stay securely in place. We were interested in creating a universe like this. No one person is the villain or antagonist but is, in a way, a victim of the structure they exist in. This is a structure that supersedes individuals.

Baishya: Sticking with objects, the gun, along with the tape recorder, is a signifier of power, powerlessness, and violence in the film. Can you discuss its significance?

Vats: The gun is one of our favorite elements in the film. We really enjoyed mapping its journey through our characters. A gun or weapon has traditionally signified power, violence, and hypermasculinity in films. We wanted to turn it on its head and have a character who is terrified of wielding an instrument of power. It was important for the gun to fulfill its function of terror in the film, but we had to find a way to do that without firing it even once. That was important to us because we didn’t want to get into the trap of illustrative violence. It was the “potentiality” of the violence that interested us. So, in a way, it is a Chekhovian element that doesn’t actually fire and yet destabilizes the world of our characters.

Baishya: One of the most striking extended sequences in the film is the last interactions between Anjani and Mahender. This begins with the party sequence, the scene where Anjani and Mahender whoop through the night with Anjani calling Mahender an “artist” and then the sequence in the back of the auto on the highway. These are moments of joy and euphoria that punctuate the precarity both characters face only to be shattered by the news of Mahender’s violent death. Can you talk about the significance of the friendship between Anjani and Mahender and how this extended scene was conceptualized, written, and developed?

Vats: How do you kill a character onscreen? How do you make that death violent without showing it? How do you make the memory of that character linger on? These are some of the concerns that informed the conceptualization and the eventual realization of the sequence you mention. It was important for the film to heighten the comfort of Mahender’s presence for Anjani before he was taken away. We felt that it would help to accentuate his absence after he is gone. Also, I emphasize that in this film we were not interested in illustrating violence. The suddenness of Mahender’s disappearance became a way to evoke the violent act of mob lynching that snatches Anjani’s best friend away.

Baishya: Can you tell us about the experience of shooting with the rhesus macaques? How did you track them and shoot them in their urban habitats?

Vats: It was the biggest challenge we faced. These animals look cute but are untrained and can be unpredictable and dangerously violent. In a way, these were the qualities that we wanted the film to have. It was crucial that we were able to film the monkeys not only in their natural habitats but also in the context of and in relation to our characters.

The writer, Shubham, and I spent months hanging around in all the areas that you see in the film. Countless days were spent just looking at monkeys and trying to figure out their schedules and patterns of movement and behavior. In Mahender, the real-life monkey repeller who plays a version of himself in the film, we had the best person to help and guide us. He would explain to us in detail the behavioral patterns of monkeys. Years of working with these animals had given him a unique insight, which we leaned on heavily during our research process.

A lot of time was also spent figuring out the technicalities of filming with monkeys. What camera best suited us, which lenses to use, what time of day to shoot which sequence—all of these and more were given a lot of attention, and all our plans were drawn up accordingly. It was a great thing that the key crew—director, cinematographer, editor, and sound recordist—all had documentary experience and were used to filming in situations where we didn’t always have control of the variables. Shooting fiction under such conditions wasn’t ideal but also exciting. Editing the material proved to be an even bigger challenge.

Baishya: There are moments when the divide between human and animal blurs and unexpected sympathies arise in the film. I was thinking of two sequences especially: the one where Anjani is caught within the cage and looks at the simians later, and the other where he shares food with the macaques. Sound often accentuates this blurring. Can you talk more about the human/simian interactions and the blurring of these divides?

Vats: Films have the power to evoke emotions for unknown, imperfect, and often flawed characters. That’s the beauty of the medium. The unexpected blurring and melting of emotion that you mention is often a similar blurring of the form—sometimes between fiction and documentary, sometimes between comedy and tragedy. Both the sequences that you mention have a similar treatment. The “playfulness” of the violence and the “tragedy” of Anjani’s discomfort in the heavy iron cage create a strange mix of emotions—which are then transposed/projected onto the monkey in the same scene. In the other scene, it seems like after all the struggle, the enmity between Anjani and the macaques melts away as soon as the job goes away. The commissioned enmity is dissolved by a simple act of sharing food. The person hired to shoo away monkeys is himself shooed away and finds comfort with his old foe. Sound is essential for this blurring to happen—it is what maps physical realities and spaces into psychological landscapes.

February 2025

Prateek Vats is an independent filmmaker based in Mumbai, India. His debut feature, Eeb Allay Ooo!, supported by the NFDC Film Bazaar and PJLF Arts Fund (Paris), was awarded the Best Film at the Filmfare Critics Awards in 2021 and Best Film / Best Director at India’s Critics’ Choice Film Awards in 2021. His feature documentary, A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings, received the Special Jury Award at the 65th National Film Awards in 2018. An alumnus of the BAFTA Breakthrough India program, he is currently working on his next feature film.

Prateek Vats is an independent filmmaker based in Mumbai, India. His debut feature, Eeb Allay Ooo!, supported by the NFDC Film Bazaar and PJLF Arts Fund (Paris), was awarded the Best Film at the Filmfare Critics Awards in 2021 and Best Film / Best Director at India’s Critics’ Choice Film Awards in 2021. His feature documentary, A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings, received the Special Jury Award at the 65th National Film Awards in 2018. An alumnus of the BAFTA Breakthrough India program, he is currently working on his next feature film.

Read Baishya's web-exclusive essay on Eeb Allay Ooo!