Digesting the Seeds of Cape Town

Taking the measure of Cape Town’s many contradictions, a visiting writer also discerns its manifold richness.

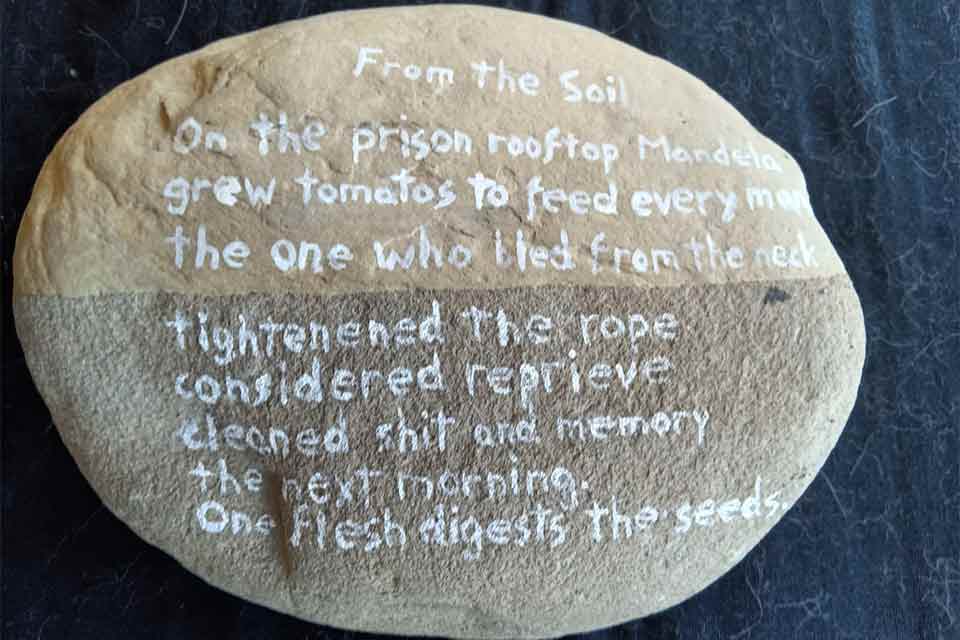

One morning, twenty-four years ago on a rocky Robben Island beach, I foraged for a stone to transcribe the poem that had come to me during a nearly sleepless night. The tour guide the day before had told me that behind the island’s nighttime silence, some ex-political prisoners like himself could still hear screams echoing from those who’d been tortured. I’d stood before Mandela’s spare cell that day, its cot covered by a meager gray blanket. In the guest house that night, my own blanket scratched the skin. I could barely distinguish between the voices outside me and those within my haunted mind. Just past dawn, I retreated to the shore, found a smooth oval stone, and lifted it into my palm. When I returned to the mainland, I brushed “From the Soil” onto its surface in white liquid paper.

Last summer, now a generation past the end of legal apartheid, I searched Cape Town for traces of what those seeds had borne. Could there even be one flesh in a country that remains the world’s most economically divided, in a city that so starkly embodies the chasm?

Many well-off Capetonians and popular tourist guides suggest the peninsula’s starkly gorgeous 1,100-meter Table Mountain unifies the city. The landmark indeed compels from any angle, its forbidding chiseled cliffs blanketed by the “tablecloth” of fog, so ripe with symbolic possibilities. Yet while the affluent enjoy its views from their homes in Sea Point and Constantia (and I had the privilege of watching the morning moon hover over the mountain bluffs as I ran the University of Cape Town cricket field), the schoolkids twenty kilometers away in Crossroads and Khayelitsha townships surely discern only a remote, abstract slab where the rich schoolkids nearby tote their laptops and promises of university.

Might we find shared flesh inside Cape Town Stadium, built alongside the tourist-friendly V&A Waterfront for the 2010 football World Cup? Only a tiny fraction of the township schoolkids will ever see a match there, even if they cheer their idols of Bafana Bafana, the national team whose name means the boys, the boys in Zulu. Out in Khayelitsha’s Mandela Park, I circled the track, watching these schoolkids compete—yellow versus green—stretching for some elusive victory. When I’d scanned the landscape days before from my descending plane, the only expressive landmarks recognizable on both sides of the M5 motorway, which splits suburb from township, were the green sanctuaries of the football fields.

On the edge of downtown, I later walked the gentle slopes of Bo-Kaap, the city’s most visually distinctive neighborhood, marked by houses painted in pastels. Bo-Kaap housed enslaved Malayans and Indonesian Muslims in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, then Indian, Coloured, and Black artisans and traders in later years. It’s a neighborhood of racial layers whose history has modestly challenged apartheid’s rigid segregations.

So, I understood why so many “Free Palestine” murals called from the residential façades as I walked to a solidarity fundraiser at the Bo-Kaap Deli. Inside I sampled a Malay-style koeksister pastry with rooibos tea. When the featured brass band, Kujenga, took a set break amidst a young, multiracial crowd dotted by hijabs, I found myself standing between trumpetist Bonga—with goatee and black beret cast straight from Blue Note 1971—and trombone player Tamzyn, barely taller than her vertically inverted instrument. When I said I’d caught something New Orleans in their vibe, a friend beside me suggested kinship: “We, too, are a Creole people.”

I’m not implying Cape Town could ever somehow achieve a graceless ensemble, let alone the flesh of unity. But returning home that night from Bo-Kaap, I heard the collective echoes of a wounded jazz.

San Francisco