Schlemiel & Schlimazel

From the Middle Ages to Seinfeld, schlemiel and schlimazel characters enjoy an interesting history. Veronica Esposito traces this history and considers why the idea of the schlemiel has survived and resonated so widely.

Coming into existence sometime in the Middle Ages, as the Jewish communities throughout Europe grappled with continual dislocation and mistreatment by the dominant culture, the notion of the schlemiel was destined for a long and interesting literary life—continuing to this day. In order to offer its translation, I will need to pair it with the Yiddish word schlimazel, as these words often go together; their most succinct English translation is commonly stated as follows: a schlemiel is somebody who tends to spill his soup, and a schlimazel is the person it lands on.

A schlemiel is somebody who tends to spill his soup, and a schlimazel is the person it lands on.

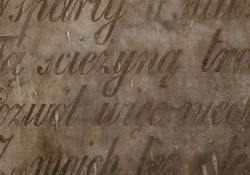

Both words begin with sch, which is common in Yiddish, often indicating derision; English speakers will recognize it from the from oft-used formation such as “problems schmoblems—I’ll show you real problems,” or the word schmuck. Schlimazel derives from the Yiddish phrase schlim mazel, which means “rotten luck” (the mazel of course coming from the celebratory Hebrew toast mazel tov). The derivation of schlemiel is less clear, although there is agreement that the word was popularized by Adelbert von Chamisso’s 1813 novella Peter Schlemihls wundersame Geschichte (The Wonderful History of Peter Schlemihl), which stars one Peter Schlemihl, who makes a deal with the devil and ends up losing his shadow.

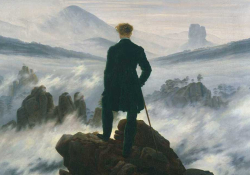

Yiddish literature scholar Ruth R. Wisse locates the schlemiel, schlimazel, and associated types as emerging from the figure of the Jewish fool, which developed in the Middle Ages as a way of mediating the encounters of Jewish people with dominant European cultures. She goes on to conjecture that the figures of the schlemiel, schlimazel, and others were likely valuable to a people living a precarious existence, without a land to call home, and subject to frequent persecution.

Yiddish is believed to have originated around the tenth century, as Jewish speakers of Romance languages who were conversant in Hebrew or Aramaic for religious purposes arrived in the Rhine Valley, interacting with other Jewish people who spoke German. From this mixture of languages and culture the Yiddish language was born. Utilizing Hebrew script, the first written Yiddish is typically dated to 1272, with a blessing that someone jotted in a Hebrew prayer book.

Yiddish began to develop its own literary works around the fourteenth century, and by the late nineteenth century it had emerged as a major language among Jewish people in eastern Europe, seen as a force that could hold the community together, be a source of shared cultural heritage, and help resist assimilation. It was at this point that the language began to develop a collection of writers and intellectuals working in it; the language remains a relative outlier in the sense that it has developed a rich literature in spite of not being a national language.

In the early twentieth century, as Yiddish peaked in cultural significance, the number of Yiddish speakers also peaked, numbering around eleven million. That number declined precipitously during the Holocaust, and Yiddish continued to decline in the decades following World War II. Today the language is spoken by around half a million people, low enough to be considered a “vulnerable” language according to UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.

Perhaps the best-known creator of a schlemiel character in Yiddish literature is Sholem Aleichem (whose character Tevye the dairyman would later achieve grand renown as the inspiration for Fiddler on the Roof). Aleichem, who has been called the Mark Twain of Yiddish literature, embodied the schlemiel in his character Menachem Mendel, which he developed through stories written from 1892 to 1913. Aleichem’s Mendel is a prototypical character of Yiddish literature: the impoverished, luckless man whose schemes for getting rich continually fail. The Yiddish Book Center describes Mendel as “always seeking a livelihood but not seeking it where a livelihood was to be found. His exasperated wife had no luck bringing him down to earth.” For all the schlemiel’s ineptitude, there is a strength to this character, a persistence and a belief that he will triumph, and many have noted that this is what makes Mendel significant, transforming him from a mere failure into a hero.

Aleichem died in the Bronx in 1916 where, in the words of Isaac Bashevis Singer, “he had begun to paint with great talent . . . an American Menachem Mendel.” It is significant that Aleichem may have been translating the idea of a schlemiel into the American context, because it is here, in its adopted home, that the concept has taken on entirely new force and meaning. Just as Yiddish was reaching its zenith in eastern Europe, Yiddish and the figures of the schlemiel and schlimazel were becoming immensely popular in America alongside vaudeville. Charlie Chaplin was, of course, one of the principal schlemiel figures to emerge from that tradition, his tramp figure making him a megastar in Hollywood cinema.

As forces like vaudeville and Chaplin’s tramp began to transform entertainment, they created a context in which Yiddish could flourish in the United States and make a uniquely colorful contribution to American English. Now it is commonplace to marvel at all the strangely perfect contributions that Yiddish makes to our language, all the words that feel so pleasurable to pronounce to lips and tongues accustomed to the rhythms and sounds of English. Words like nosh, schtick, chutzpah, and klutz are so ubiquitous that we often don’t even realize that they are all borrowed from a language created in a very different place.

As the schlemiel began to emerge in American storytelling, it also began to transition into a figure that spoke to the widespread, modern experience of disempowerment. This perhaps helps explain the well-documented, long-standing presence of the figures of the schlemiel and schlimazel in American storytelling. An early instance of this character can be seen in the minor character Cohn in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, who has been identified as a schlemiel for his puerile behavior and his continual blundering into humiliation. Later instances of the schlemiel in American literature would include Polish American writer and Nobel laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer’s career-making story “Gimpel the Fool” as well as Saul Bellow’s Herzog and antiheroes from the major novels of Thomas Pynchon and Philip Roth. The character would continue to be a major presence through the 1970s and ’80s in the antiheroes of the films of the now-disgraced filmmaker Woody Allen.

A degree of sexism is inherent to the concept of the schlemiel.

As this list perhaps brings to mind, the schlemiel is typically male, and many have pondered if a female schlemiel can even exist. One thing that makes the schlemiel prototypically masculine is that the archetype tends to rest on notions of humiliation and disempowerment, and for most of the word’s history women have simply not had the privilege of possessing enough social status to experience the kind of humiliation typical of the schlemiel. For another thing, women tend to play an auxiliary role to the schlemiel—that of the nag who adds to the schlemiel’s cosmic bad luck. As this may make clear, a degree of sexism is inherent to the concept of the schlemiel. Individuals such as the comedian Joan Rivers and the politician Sarah Palin have been proposed as female schlemiels—the former for her brash comedy (not befitting of the stereotypical modesty expected of women), the latter for her ascension to power despite her inherent ineptitude—yet the word seems, for the most part, exclusively male.

In the 1990s, the schlemiel and the schlimazel took on new life with the emergence of the sitcom Seinfeld as one of the major American cultural phenomena of that decade. Writing in the Journal of Popular Film and Television in 1994, Carla Johnson was one of the first to identify George Costanza and Jerry Seinfeld as a classic schlemiel/schlimazel duo. As Johnson puts it, George is the schlemiel, the one who seems cosmic and existential in his lucklessness, whereas Jerry is merely the schlimazel, the one whose ill luck is more circumstantial, typically revolving around his connection to George the schlemiel. “As the schlemiel’s world centers around his essential lucklessness,” she writes, “the schlimazel’s world centers around situations, the mundane, everyday pains and pleasures of life. Thus, in another episode, when George cries out, ‘There’s a void, Jerry, there’s a void. What gives you pleasure?’ Jerry, the schlimazel, replies, ‘Listening to you. Your misery is my pleasure.’ Here, Seinfeld has described his character’s philosophy on life, which is ‘To outorder someone in a restaurant, to get the better thing, that’s the true contest of life.’ Jerry is like the Hasidic fool of the nineteenth century, a ‘simple man who lives happily, one day at a time.’ The contrasting mindsets of George and Jerry provide much of the tension and intellectual framework of the show.”

In the 1990s, the schlemiel and the schlimazel took on new life with the emergence of the sitcom Seinfeld.

Seinfeld has widely been proposed as among the greatest TV shows ever made. It was the first show to garner $1 million per minute in advertising revenue—placing it into the category of the Super Bowl—and, much as Yiddish has, it has given American English numerous new words and terms, among them: regifting, close-talker, Festivus, spongeworthy, shrinkage, and mimbo. It’s not hard to see how many of Seinfeld’s most popular and lasting contributions to the American vernacular derive from the essential lucklessness and continual humiliation of its schlemiel and his schlimazel counterpart.

Proposing the schlemiel as an archetype of the modern hero, Wisse has claimed that “the schlemiel’s misfortune is his character. It is not accidental, but essential. . . . Whereas comedy involving the schlimazel tends to be situational, the schlemiel’s comedy is existential, deriving from his very nature in its confrontation with reality.” When framed in this way, it begins to make sense why the idea of the schlemiel has survived the rise and fall of the Yiddish language and has come to be a concept that has resonated so widely. I imagine that the word still has much mileage left in it, and am curious to know where it might go next in a world that often feels full of so much that is relevant to a schlemiel’s life.

Oakland, California

Editorial note: For more, check out the award-winning anthology How Yiddish Changed America and How America Changed Yiddish, edited by Ilan Stavans and Josh Lambert (Restless Books, 2020).