Poetry’s Syncretic Mishmosh: A Conversation with Robert Pinsky

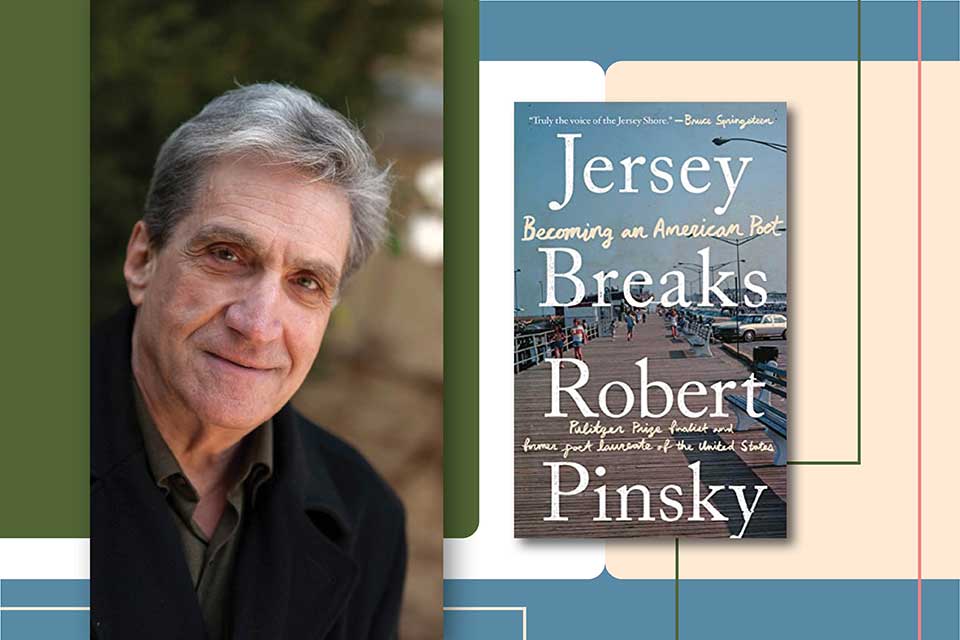

As an eminent poet, translator, man of letters, teacher, anthologist, literary ambassador, family man, and clear-eyed witness to America’s zeitgeist and character over the past half century, Robert Pinsky has written both personally and publicly with a parallax vision that has divined, on one hand, what Walt Whitman called “the genius” of America’s “common people” and, on the other, what the critic J. D. McClatchy called Pinsky’s gift for transforming “those autobiographical myths we make out of memories” into poetry. I was particularly curious at the outset of our conversation about what early personal experience prompted Pinsky to begin writing in the first place. What first book or fictional character in his youth had stirred him into thinking about poetry and literature in general? He responded, “James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses.” I next asked, Why those books in particular? He wrote back that even at the young of age of twelve he identified with Stephen Dedalus’s desire “to wake from the nightmare of history.”

As an eminent poet, translator, man of letters, teacher, anthologist, literary ambassador, family man, and clear-eyed witness to America’s zeitgeist and character over the past half century, Robert Pinsky has written both personally and publicly with a parallax vision that has divined, on one hand, what Walt Whitman called “the genius” of America’s “common people” and, on the other, what the critic J. D. McClatchy called Pinsky’s gift for transforming “those autobiographical myths we make out of memories” into poetry. I was particularly curious at the outset of our conversation about what early personal experience prompted Pinsky to begin writing in the first place. What first book or fictional character in his youth had stirred him into thinking about poetry and literature in general? He responded, “James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and Ulysses.” I next asked, Why those books in particular? He wrote back that even at the young of age of twelve he identified with Stephen Dedalus’s desire “to wake from the nightmare of history.”

In our lengthy email conversation that followed, he wrote wisely, graciously, and knowledgeably about important “moments” in both his personal life and his seminal career as a poet, teacher, accomplished saxophone player, celebrator and publisher of Americans’ favorite poems, Jewish kid growing up in Long Branch, New Jersey, in the 1950s, international citizen, United States Poet Laureate, tireless co-translator of Czesław Miłosz’s poetry with Robert Hass, and so much more, which caused me to realize after our last email exchange that the significant parts of his life and career serve as exemplary sums in themselves, which in turn concatenate as extraordinary accomplishments that signify myriad wakings from “the nightmare of history.”

Chard deNiord: You conclude the second chapter of your recent memoir, Jersey Breaks, with a striking observation about the source of “everything,” by which you seem to mean the enmity you witnessed in your neighborhood in Long Branch, New Jersey. You give examples: “my mother’s fantasy about Mr. Cutter’s dead mother . . . Dr. McKelvie being prevented from swimming at Cramer’s Beach . . . strawberry-nosed Mr. Cutter hating Jews—all of that went deeper than handwriting or swimming, deeper in a way than even hating or dying. Everything came from a nameless, densely crazy power that ruled the world. Even poetry and music, even sex—all were on its dark agenda.” As a young man, did you turn to poetry in an attempt to attack “the densely crazy power” that “ruled the world”?

Robert Pinsky: That sentence about the power that rules the world—in my mind, it is about culture. Or maybe “Culture” with a capital C—but I can see why you say it seems to mean local enmities. “Everything” is whatever James Joyce’s autobiographical character Stephen Dedalus means by history, which he defines as “the nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” My autobiographical character, Robert Pinsky, thinks about bits of culture: his mother’s fantasy or myth about a corpse in a steamer trunk; a neighbor, the Black physician Dr. Julius McKelvie, trying to correct the insane laws or customs concerning ancestry and bathing in the Atlantic Ocean; our alcoholic landlord Mr. Cutter hating Jews; left-handed handwriting . . . all of these great cultural absurdities are also great, potentially lethal powers. The crazy monster “Culture” or “History” even controls desirable realities like sex and poetry. That is the subject of Jersey Breaks.

deNiord: You read Joyce’s Ulysses with what you call the same “religious ardor” you also brought to the poetry and fiction of Elizabeth Bishop, Franz Kafka, Emily Dickinson, Isaac Babel, Ralph Ellison, Alan Dugan, Sophocles, Mark Harris. Why exactly did Joyce’s characters, Stephen Dedalus and Leopold Bloom, appeal to you so strongly as young men in search of a way out of what you call their “nightmarish” worlds? What did you find so fascinating in his characters, or true about yourself, in post–World War II America?

Pinsky: I was too young to think of Leopold Bloom as a young man. As I do, now, about that thirty-six-year-old! Stephen interested me because he was a provincial (like me), molded by his familiar province, like me, and profoundly eager to rise above it and outside it, like me. I suppose the thoughtful Jew Leopold was important to me—certainly more sympathetic than that arrogant young prig Stephen—but the Jews in literature that interested me were the Odessa gangsters of Isaac Babel’s stories. They resembled my grandfather, the tough-guy mobster Dave Pinsky. Also, of course, Babel’s autobiographical character Isaac Babel, who, like Stephen, was trying to awaken from that nightmare, history. Like Stephen, Babel sets out to awaken by the means, partly, of writing. Unlike Stephen, he also sets out to awaken by means of the Bolshevik Revolution, and by understanding the Cossacks of the Red Cavalry.

deNiord: The specific examples you cite above of what Robert Penn Warren called “moral turpitude” must have made a deep impression on you as a child and adolescent. I’m curious about just when you developed your moral imagination, to the point where it became a lifelong passion. Unlike Walt Whitman, who lived just up the road from you in Camden, New Jersey, and wrote in such an effusive, celebratory way about American democracy as well as what he called “the genius” of the American people, you have chosen to witness to what Hannah Arendt called “the banality of evil” in America, as if witnessing America’s horrors were more important than focusing solely on America’s “genius”—unless, of course, you want to call America’s history of criminality “genius.” Was there a specific incident that triggered your moral imagination in adolescence, or a series of incidents, that set you on your course of witnessing to America’s schizophrenic national character?

Pinsky: What are the origins of anyone’s moral imagination? This is a challenging question for me. You make me think of an element in my writing about our American culture and society that I recognize as moral—but I hope not moralistic! The words “moral” and “evil” were not part of my family’s way of being Orthodox Jews. The lower-class religious education inherited from the villages of eastern Europe emphasized literacy as a function of ritual: to say the prayers properly required ten circumcised males who could read aloud the words of the sacred texts. The exquisitely nuanced moral discussions of the scholarly elite were absent, or at most a rumor from above.

Verbal proficiency of a limited kind—chanting the prayers in Hebrew—was valued but minimal. We learned it by rote, repetition, and melody. The primacy of sound and community over understanding, in its weird way, heightened the moral intensity. It was not rational. Survival of the Jews depended on saying aloud certain words, no matter how opaque they might seem to any one person. Unlike, say, Gregorian chants, our ritual voices were simultaneous rather than choral—everybody muttering the same prayer at the same time—which somehow made the services feel even more communal—though alienating in a personal way.

The opaque, familiar prayers, the dietary laws, the holy days; all those forms of repetition were both tedious and a moral necessity. Thrillingly the opposite was the language of daily life.

The moral meaning was communal and visceral. Any one person’s moral imagination was a subordinate vehicle for that persisting shared content. Being one among minyan of ten or more chanting the ritual of meaning was supposed to exalt you by participation. And in a way, it did. The opaque, familiar prayers, the dietary laws, the holy days; all those forms of repetition were both tedious and a moral necessity.

Thrillingly the opposite was the language of daily life—the gossip, arguing, joking, news, political commentary throbbing its erratic way through the language of a family, or a neighborhood, or the newspaper, the radio and television, the movies. Mark Twain and Lewis Carroll. And not just language: on the radio, Jack Benny and Verdi and Duke Ellington and programs like the Inner Sanctum or The FBI in Peace and War. Predilections and pleasures, inventions and adventures, trivial or profound or probably both at once—it was all heightened by contrast. And I can’t call it “secular” because it included Christianity: the many-headed reality that eventually became, along with Judaism, a lifelong object of interest and resistance, quotation and ridicule.

The tiny minority religion sang and muttered its persistent survival from a space outside of the traditions shared by the vast Christian majority—Protestant or Catholic, white or Black. The rituals provided, every day, a dynamic interchange between a sacred periphery and the engaging center. Beyond any merely binary us-and-them, the contrasts and hybrids were thrilling: tootling the clarinet part for a simplified version of Handel’s Messiah or thrilling to the gospel-created voice of Sam Cooke. Applauding the irreverence of Mark Twain or of Henny Youngman. Treasure Island and the Odyssey and The Searchers. I guess my moral imagination, prizing mixtures over purities, has been formed by that syncretic mishmosh, and maybe the idea of an inspired mishmosh.

My moral imagination, prizing mixtures over purities, has been formed by that syncretic mishmosh.

deNiord: At a college forum once you summed up America’s dilemma succinctly “as an unfinished, defective, and sometimes glorious project with its erratic orbit between the cross-fertilized poles of democratic genius and populist vulgarity.” This national “dilemma” has been what Emily Dickinson called a “flood subject” of yours almost from the time you started reading books like Ulysses as an adolescent, prompting you in the early 1990s to undertake the formidable task of translating Dante’s Inferno. Am I wrong in assuming that this literary venture grew out of your moral fascination with the problem of evil that has recurred throughout human history and in American politics and society? Are there any sins in The Inferno that you might think of as specifically American transgressions?

Pinsky: Well, I guess the Commedia and especially the Inferno could be described as a syncretic mishmosh. Personal grudges and cosmology, classical learning and papal delinquencies, special effects and lyricism, highs and lows in language and everything else. The prevailing sin in Inferno, I believe, the transgression Dante found strongest in himself, is acedia, the Thomistic “sorrow of the world”: despair. In English, “wanhope.” The soul destroying itself, by believing it is evil beyond redemption. Isn’t that the prevailing sin in our literary and academic realms? In our contemporary jargon, despair.

In our culture at this moment, despair takes the possibly fatal, terminal form I try to evoke with the phrase “populist vulgarity.” Does the notion of a democratic culture proceed from aspiring to be universally noble, or does it mean becoming so anti-elitist that we are stupid?

If this were a lecture, at this point I would quote from W. E. B. Du Bois’s essay “Of the Training of Black Men,” especially the final paragraph. Or another reference, from Mark Twain: are the revivalist showmen the Duke and the Dauphin going to prevail, here in the twenty-first century? That seems possible—that pair are in Congress and all over the internet—but maybe not inevitable.

deNiord: I’m curious about your obsession with sound, and breath, and voice in your verbal music. You have written primarily in form throughout your career, employing traditional forms, primarily blank verse, in crafting your “meter-making arguments.” You write in Jersey Breaks that you were “blessed by growing up with a certain version of what can be called an oral tradition.” What exactly was that “oral tradition,” and how did you come to revere it as “sentence melody,” in which the actual sounds of letters—consonant, vowels, diphthongs—represented spell-like magic?

The first generation of poets in modern English were making new music in [the language], freely importing (often through Italian) the Persian or Arabic feature of rhyme.

Pinsky: For me, all language worthy of the word—it is, after all, French for “tongue-using”—is bodily. That fact gives it form. My mind resists the phrase “spoken-word poetry” because, like “language poetry,” it feels redundant. Scholars date modern English as beginning in the year 1500. Maybe that is related to the articulate joy and inventive music of Campion, Dowland, Gascoigne, Sidney, Greville—the first generation of poets in modern English. It was new, they were making new music in it, freely importing (often through Italian) the Persian or Arabic feature of rhyme, unknown in the Greek or Latin models for European poetry.

I think of my grandparents and parents and their generations of immigrants from many places, and about the Black migration from the South—and some of those who were the first in their families to be native speakers of English—as having a similar unruly joy in discovery and improvisation. The language was new to them, too, and like Campion or Sidney, they did new things with it. Jokes, legends, contentions, reductions, sermons, and speeches. But maybe jokes, especially.

I’ll harp on impurity a little more. On the pianist Herbie Hancock’s album Gershwin’s World, many classical and pop and jazz artists appear, including the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra, Joni Mitchell, Wayne Shorter, and Stevie Wonder. The songs are by George Gershwin (same age as my grandparents), but the album’s title also suggests a world: various, many-minded, improvisatory, and rich in borrowings and hybrids. The album reminds me of the modernist generation of poets—for example, Williams, Pound, and H. D. all at college together—their ear for consonants and vowels and the sounds of sentences.

That I’ve written “primarily in form”! Thank you, Chard, for the compliment to my work, which I think of as mostly free verse. One book, An Explanation of America, in blank verse, and The Inferno of Dante. But not most of Sadness and Happiness or The Want Bone or Gulf Music or the recent books. And I’ve never had much interest in sestinas, sonnets, villanelles, and such. Form for me is a necessary quality—free verse has form, if it’s any good—but beyond prescriptions and paradigms.

deNiord: You write this exquisitely ironic proverb in Jersey Breaks: “You have to be taught that you can’t dance . . . and until then you can. Same with poetry.” What did you have to unlearn specifically about what you “can’t” write, especially with regard to your academic apprenticeship in order to return to what you knew how to do as a poet and writer before you became “educated”? And in light of this seeming paradox, and as a teacher of creative writing today at Boston University, how would you instruct your students to mind García Lorca’s adage, “the second a violin knows it’s a violin, the music stops”?

Pinsky: I’m writing a little book that will (if I can finish it) try to answer this question. Poems as something people say, not products of rules and recipes. There may be very brief chapters about the limitations and defects of good, useful slogans of the creative writing industry. There might be chapters called “Showing Is Telling” or “Forms Are Not Form” or “The Speaker Is the Writer.” Maybe “Line Beginnings and Middles.” I am proud of how we writers have improved, deepened, and enriched the study of writing in high schools and universities. But as “Poet” and “Fiction Writer” have become academic job titles, with associated conventional terms and notions, we must work to avoid new kinds of pedantry.

deNiord: Bob Dylan wrote, “To live outside the law, you must be honest.” Your grandfather, Dave Pinsky, “lived outside the law” in Long Branch as a bootlegger. How did his role as your grandfather and a mobster, as you also refer to him, influence the direction of your writing and your choice of subject matter, if, in fact, it did?

Pinsky: In the chapter of Jersey Breaks called “Idolatry,” I tell about my grandfather’s disregard for religious practices. His way of life, his Christmas tree, his Protestant wife or girlfriend, his bar, his tough-guy manner, all may have made him a tempering counterforce, for me, to the Orthodox training I just discussed (a bit to my surprise) a couple of questions ago. I think that as a child I thought less about his criminal past than about his presence as a deeply integrated, respected, somewhat glamourous fixture in the lower-middle-class world of our hometown.

deNiord: Jersey Breaks combines amazing personal, poetic, and professional detail, reading one minute like fascinating fiction, but stranger than fiction, and the next like personal history in an unabashed, honest way that testifies to the converse of Socrates’ adage that “an unexamined life isn’t worth living.” On every page your reader feels your life—sometimes presented as raw or unexamined—has very much been worth living, from your struggles “to wake from the nightmare of history” to childhood days in Long Branch, with neighbors’ names and peculiarities, to your first profound reading experiences, and then ultimately to your maturation into “an artist as a young man” and eventual prominence as a major American poet, three-time national poet laureate, and director of the Creative Writing Program at Boston University.

I found every chapter engaging, incisive, and often extraordinary for what your friend Czesław Miłosz called “immense particulars” in the form of nuances, minutiae, names, imbroglios, tragedies, epiphanies, and revelations. Have you kept a diary or journal throughout your life? So much of your narrative betrays such exquisite recall that it’s hard to believe you’re simply remembering. I mean passages like this one, for instance, which betrays a precociously observant awareness of complex family dynamics observed when you were just a child:

My mother always spoke of Della as “The Barmaid,” the way she liked to call her father-in-law Dave a moonshiner or bootlegger. The nouns were another way to tease her husband. Sometimes he tried to fight back maybe by noting that Sylvia was repeating her material. It was all theater, and I was an audience. She might succeed in getting him angry, or they might start having fun, laughing together at his pedantic explanation.

This passage seems more than remarkable to me for its insight into family dynamics. How do you feel this gift of yours for interpersonal insight and observation might have applied also to your poetry writing?

Pinsky: To approach this question from another angle—why am I a perpetual, compulsive storyteller, in my poems, in my conversation, in public and in private? But not a fiction writer? In the family banter and needling you quote, I was trained from infancy by expert, inventive storytellers. But aside from a couple of so-so short stories, I have not published fiction. Maybe the explanation has to do with the vocal nature of the stories I remember and notice and emulate: voice—the supreme, best use of breath—ruled that family, and it is for me the center of poetry.

Maybe related is that I love hearing and telling jokes, but I am bored by the same material written out on the internet or in print. I can appreciate the work of Charles Dickens or Jane Austen or Isaac Babel or Ralph Ellison or Maile Meloy or Cormac McCarthy or Ha Jin . . . as a spectator or auditor.

But to create a story, I need to breathe it. My memory too is vocal. I am not a note-taker. In school, I would buy notebooks and do nothing but doodle in them. In my way, I retain a lot. And, of course, make up a lot.

deNiord: Robert Hass and you collaborated over many years in translating the poems of Czesław Miłosz, the great Polish poet who won the Nobel Prize in 1980. Here is a profound stanza from Miłosz’s poem “Ars Poetica,” which you and Hass translated:

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at will.

What I’m saying here is not, I agree, poetry,

as poems should be written rarely and reluctantly,

under unbearable duress and only with the hope

that good spirits, not evil ones, choose us for their instrument.

What was it like to participate in this daunting project of translating Miłosz, and how much did his poetry play a role in influencing your own subject matter, conceits, sensibility, and sense of literary ambition?

Pinsky: Working with Bob and Czesław in those years was a blessing that confirmed what I hear in these lines you quote: that history is everywhere and in everyone. A vast, multiple presence with so many dimensions and guises that it is mostly invisible. History, not as the doings of governments or armies, but the ideas, loathings, affinities, aspirations, disappointments, and realizations of the inherited past. The house of my self or of my poetry is open to all sorts of traffic. Not necessarily determined by that traffic but inevitably, as the translation says, open to it. The translation project—if “translation” is the right word for what we did: Czesław and Renata Gorczynski, being bilingual, produced trots that Bob and I, knowing no Polish, tried to make into English versions that Czesław would approve. That process for Bob and me involved trying to think as “invisible guests” of our own native language—and for Czesław as for us, the effort involved a variety of guests visible and invisible. Translation is haunted—as is any other kind of writing, in less manifest ways.

The house of my self or of my poetry is open to all sorts of traffic.

deNiord: You have also translated the Venezuelan poet Rafael Cadenas, who wrote: “The soul is always in danger. But I don’t want to elaborate on that claim. I prefer to leave it like that, simple. I want to tell you a feeling that I always carry: living and doing what human beings do, knowing ourselves to be fleeting, moves me to believe that there is a sustaining force outside of me. . . . The idea is to be present, open, attentive, up with reality, with what is happening. Amante, at the end, expresses what I am trying to tell you, which is central for me. Worrying about happiness is just for adults. ‘As a child,’ says Alistair Reid in my translation of phrases attuned to Zen, ‘I did not know what happiness was and whether I was happy or not. I was too busy being.’” He added, “I am tied—strapped—to reality, which is always fantastic but rarely presented as such. In this sense, certainly, I always accompany Borges.”

I can see why Cadenas’s poetry has appealed to you also. The psychic condition of being “strapped to reality, which is always fantastic but rarely presented as such,” resonates throughout your work. Long Branch, New Jersey, and America itself are “realities” you willfully strap yourself to in the process of writing; realities that appear ordinary at first, as in your poems “Shirt” and “An Explanation of America,” but opening up in the process of your writing into fantastical and astonishing “news”—your discovery of things you didn’t know you knew. Would you talk about a few of your poems in which you, in the course of writing them, discovered your “real” subjects and expression that surprised you in a mystical way as emanating from an “other,” as Jorge Luis Borges would say?

Pinsky: Marianne Moore and William Carlos Williams in one way, and Alexander Pope in his imitations of Horace in another way, inspired me, at a certain time in my writing life, to try writing a poem in response to each thing I literally or in effect touched. Each next thing as the prompt. “Shirt” is related to the sequence “First Things to Hand.” The etymology of the word thing—originally, it was a verb meaning to convene to discuss issues, thyngan—obsessed me for a while: each thing is a meeting. Each thing is a convocation of voices—Miłosz’s “guests,” welcome or unwelcome. So that in composing “Shirt” I am surprised by doors inside me that open on kilts and Koreans, and through the doors inside me while writing, here came the Buchenwald of the Holocaust and the Loki of mythology and Lancelot. And “Door” and “Pliers” welcome the “plaited filaments” of the crucifixion and my cat . . . subjects are occasions, I guess. And it is all personal, unpredictably, with the personal—I hope—giving the ardor of a focus. The idea of doors makes me remember my poem “Window.” . . . Thirty years ago or a bit more, I was already thinking about identity and universalism in ways that persist in Jersey Breaks—related, I think, to what Miłosz says about the difficulty (or impossibility?) of remaining one person.

Your category-window of being, say, male, American, Jewish, heterosexual as something you look out of, peer out from: your aperture but not your cell. As I write this response to your question, just now, I just got an email from someone quoting an introduction I wrote for a book of stories by Leonard Michaels (another Berkeley figure). In his great story “I Would Have Saved Them if I Could,” Lenny wrote:

Stories, myths, ideologies, flowers, rivers, heavenly constellations are the phonemes of a mysterious logos; and the lights of our cultural memory, as upon the surface of black primeval water, flicker and slide into innumerable qualifications.

My introduction’s paraphrase for this sentence of Lenny’s is: “however darkly and impenetrably, we are all related. . . . The pomposity of public language and the nattering of private sensibility equally neglect this truth of our shared impurity or doubleness.”

deNiord: In Jersey Breaks, you mention jokes, prayer, and song as invaluable sources for poetic language. By song, I mean to include music in general. I’m assuming you think your saxophone “sings” when you play it and your breath punctuates harmonic “lyrics.” In what specific ways do you feel both oral and aural modes of expression have played in the composition of your poetry?

Pinsky: The great, seminal horn player Lester Young gave advice, often quoted, about how a horn player should play a ballad: know the lyrics and think about what they mean—what the song is about. The tenor saxophone, some say, is the most vocal instrument. I try to do in my poems what I could not do well enough with the horn: to return to the theme each time, building more emotions, more surprise and more coherence, more inevitability and more wildness, each time. An exercise for the saxophone player is to produce the effect of the register key—entering a higher harmonic—entirely with your throat, not your fingers. You sing the horn into the higher register, with your vocal cords. To exaggerate a little, the difference between singing and poetry is a matter of degree. Who can read Dowland’s “Fine Knacks for Ladies” without understanding that of course it is a song as well as a poem? Who could fail to hear it? I guess the answer to that question might be, “An eminent literary scholar.”

I try to do in my poems what I could not do well enough with the horn.

deNiord: That way of considering song reminds me that as US Poet Laureate from 1997 to 2000, you founded a nationwide program: the Favorite Poem Project. This involved asking people from all walks of life to name a favorite poem, read it aloud, and describe its value to them in short videos. The FPP was a huge success, administered by the brilliant young poet Maggie Dietz. You believed, you have written, “that contrary to stereotype, Americans do read poetry; that the audience for poetry is not limited to professors and college students; and . . . that there are many people for whom particular poems have profound, personal meaning.” Do you yourself have a favorite poem, or a few, that have stayed with you throughout your life?

Pinsky: As I recount in Jersey Breaks, memorizing “Sailing to Byzantium” when I was eighteen years old kind of marked a transition: from one fantasy life to another, my saxophone to my voice, from Lester Young to William Butler Yeats. The melodies of Yeats’s poem, although I did not much understand its meanings—what was “the artifice of eternity”?—formed me. And that experience formed the Favorite Poem Project. A few years later, sixteenth-century song-poems like “Fine Knack for Ladies” and “Now Winter Nights Enlarge” deepened the process—and made me an even more unlikely inhabitant of the process—by extending it far back in history. “The Snow Man,” by Wallace Stevens; “Silence,” by Marianne Moore; “Fine Work with Pitch and Copper,” by William Carlos Williams—those, too, are embedded in me. “At the Fishhouses.” “Those Winter Sundays.” “Ode to a Nightingale.” And somehow combining the sixteenth and twentieth centuries in its appeal, for me, George Gascoigne’s “Gascoigne’s Woodmanship.”

deNiord: Speaking of the national attention you’ve received as both a celebrated poet and unprecedented three-term US Poet Laureate, I think of two public events you were involved in, both of which you discuss in Jersey Breaks, that couldn’t be more disparate but also equally momentous as “soul-making.” The first involves a trip you took to Los Angeles in the fall of 2001 to appear as a voice actor in an episode of The Simpsons titled “Little Girl in the Big Ten,” in which you play, as you write in Jersey Breaks, a “hammy version of yourself” at a college coffee house poetry reading, and the second, a speaking engagement on September 16, five days later.

That week turned out to be a traumatic experience for you as well as the entire nation. You flew out to Los Angeles on September 10, 2001, on the same flight that crashed into one of the World Trade Center towers the next day, and then five days later you were in the challenging position as the US Poet Laureate of having to read a few poems at a speaking engagement at the Old Main Library in Cleveland. One of the poems you chose to read was Czesław Miłosz’s “Incantation” (in your translation), which opens with this line: “Human Reason is beautiful and invincible.” You observe that these words are “so unlikely for an American poet to write that some readers assume that Miłosz is merely joking.” You, however, don’t think so, praising Miłosz’s claim at the end of his poem for the intellectual force that “opens the congealed fist of the past.” What do you think Miłosz, a relatively new American citizen when he wrote those lines, meant exactly by his belief in the sanguine power of “reason”?

Pinsky: Well, as a Catholic intellectual, Czesław had absorbed and pondered the Thomistic or Augustinian idea of reason as a sense. Not merely “logic” or syllogistic processing but a faculty. As sight perceives appearances and smell perceives smells and so forth, reason perceives general principles—or, to put it differently, truth. In the present year of 2023, with resistance to science a kind of right-wing principle, the ending of that poem has new relevance, maybe:

Beautiful and very young are Philo-Sophia

And poetry, her ally in the service of the good.

As late as yesterday Nature celebrated their birth . . .

Philo-sophia, the love of knowing. The poem—written by someone who had experienced full-blown, flourishing fascism—dares to invoke the idea of truth.

deNiord: Miłosz came of age in a different world, and lived in a different United States than the present one. Given the proliferation of MFA programs, over three hundred now—along with the inundation of online poetry and poem-of-the-day websites and desktop publications of poetry books not even the Library of Congress can keep up with—it’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the amount of poetry available in the marketplace and on the internet. The wonderful poet Charles Wright has described poetry as language that “sounds better and means more.” What do you feel is the best way to uphold one’s faith in American poetry today? Is it to maintain faith in the age-old efficacy of poetry’s “still small voice” amid and within the flowering of unprecedented multitudes? Is it still to believe in the transcendent genius of “Poets to Come,” to write the “main things” as Whitman advised, despite so many contemporary poets’ radical experimentation with forms, conceits, and theories that challenge poetry’s traditional definitions and criteria?

Pinsky: One of my personal slogans is, “Thank god for boredom.” Without it, all the fads and bullshits of all time would continue to flourish. The elevation of Edgar Guest (and I guess he was not all bad, just mostly) was not corrected by critics or scholars: the corrections and adjustments come from the patient, untiring mills of boredom and interest, churning away so that people do give voice to work by the nobodies Hopkins and Dickinson, while Guest and Colley Cibber and Mary “Perdita” Robinson and Nahum Tate’s cheerful rewrite of King Lear (happy ending!) are remembered only by antiquarians. And let’s be humble: Wyndham Lewis’s The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse contains work by canonical immortals. (The title is from Wordsworth.) Maybe work by you or me, or work we admire, will be in somebody’s Stuffed Owl. I don’t trust the judgment of critics and prizes and academies, but I do trust the cleansing force of boredom—and yes, in the long run, of boredom’s opposite, too.

deNiord: Of all the books of poems (how many now?) you’ve written, is there one in particular, or maybe even just one poem, that woke you “from the nightmare of history,” and is this something you feel a person must do on his or her own by writing instead of, say, reading?

“Meaning” tries to acknowledge my debt to Ezra Pound and my loathing for him, with an incidental tribute to Keely Smith.

Pinsky: Each time I write anything, or publish anything, or read anything, I’m driven by this question. So my most recent poem (today it is one called “Meaning”) is always the earnest, if incomplete, answer. The poem tries to acknowledge my debt to Ezra Pound and my loathing for him, with an incidental tribute to Keely Smith. Like my earlier “Ode to Meaning,” this poem is a wistful endorsement of meaning, as, at the very least, a possibility.

deNiord: W. H. Auden claimed that “mad Ireland hurt” Yeats into poetry. Do you feel, looking back on your career, that mad America hurt you into poetry?

Pinsky: Yes.

March 2023

Editorial note: Read Pinsky’s poem “Forgiveness” from this same issue.

Robert Pinsky’s recent autobiography is Jersey Breaks. His books of poetry include At the Foundling Hospital, The Want Bone, The Figured Wheel, and his translation The Inferno of Dante. Among his prose works is Democracy, Culture, and the Voice of Poetry. He has appeared on The Simpsons.