Presence in the Book

Native dream songs are forever in the clouds, and once more the empire wars are underway. The lilies and daffodils are in bloom, and at the same time we hark back to the stories of shamans that war never ends, since evil, envy, greed, and predatory vengeance never end. The last empire war started with a royal murder, and the next world war of resentments and revenge starts with the fiery purge of books and libraries.

—Gerald Vizenor, Satie on the Seine: Letters to the Heirs of the Fur Trade (2020)

“I am in the book,” pronounced Edmond Jabès in The Book of Questions. “The book is my world, my country, my roof, and my riddle. The book is my breath and my rest. . . . I have followed a book in its persistence, a book which is the story of a thousand stories as night and day are the prow of a thousand poems. I have followed it where day succeeds the night and night the day, where the seasons are four times two hundred and fifty seasons,” wrote Jabès.

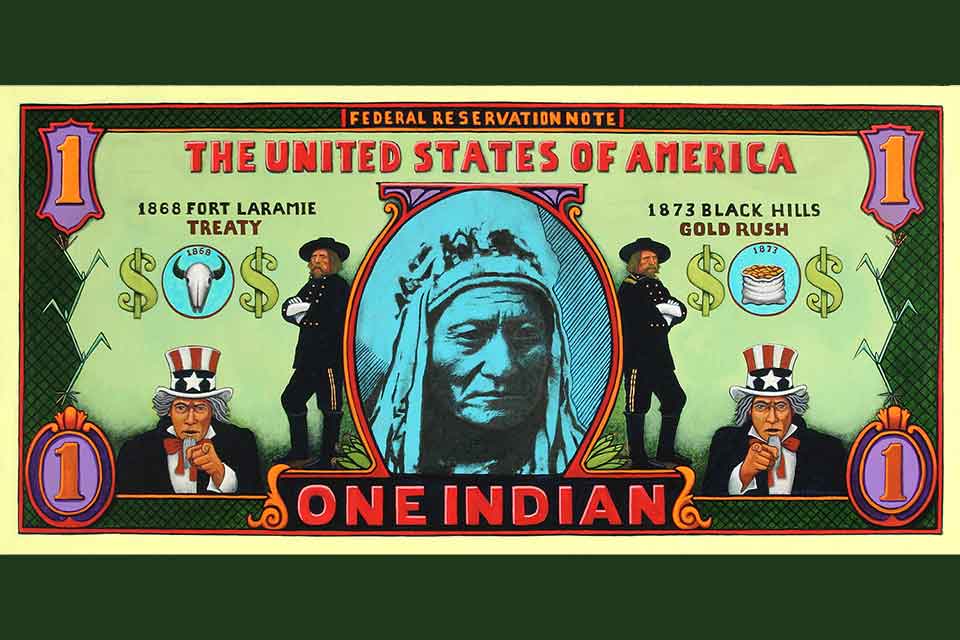

Native American authors are in the book and reveal the trouble and timely tease of books, or as Jabès commented, “the torment of the books.” Natives are in three leagues of torment in the books, as the misnamed natives of discoverers, colonists, and counterfeit histories, the grandeur of the noble savage, and the critical tease and creative literary art by native authors. The gossip theories of race and betrayals of nations were denounced in the first books by native authors in the eighteenth century, and later ethnographic monographs were rightly mocked, and the rush of cultural models were deconstructed as ironic native stories of survivance.

Cristoforo Colombo misnamed natives the Indians, and Amerigo Vespucci described natives as “worse than heathens; because we did not see that they offered any sacrifice, not yet did they have a house of prayer.” Puritan John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Bay Colony declared natives “enclosed no land, neither have they any settled habitations, nor any tame cattle.”

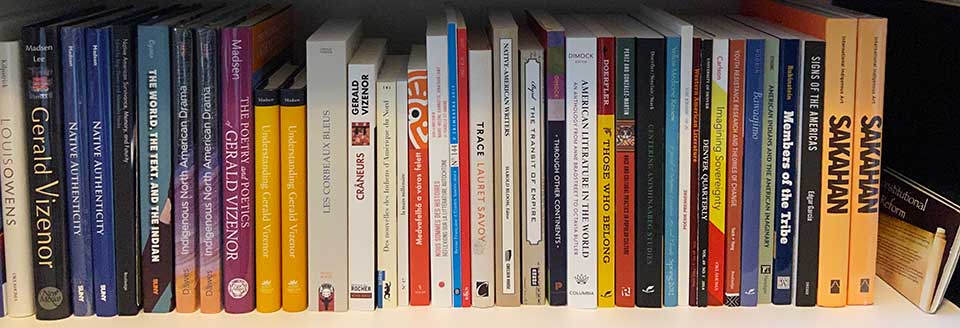

Critical literary memories are the future of books, the very nature and presence of printed books in the familiar world of libraries, timely ironies, and poetic perceptions of the colophon, deckle edge, and cover art.

Critical literary memories are the future of books, the very nature and presence of printed books in the familiar world of libraries, timely ironies, and poetic perceptions of the colophon, deckle edge, and cover art. The reminiscences of printed books are not present in the future tense of computer technology or the algorithms of artificial intelligence. The primary perceptions of the actual books are hardly realized on the internet or ebook readers.

“The books have voices. I hear them in the library,” wrote Diane Glancy in Designs of the Night Sky. “I know the voices are from the books. Yet I know the old stories do not like books. Do not like the written words. Do not like libraries. The old stories carry all the voices of those who have told them. When a story is spoken, all those voices are in the voice of the narrator. But writing the words of a story kills the voices that gather in the sound of the storytelling. The story is singular then. Only one voice travels in the written words. One voice is not enough to tell a story. Yet I can hear a voice telling its story in the archives of the university library. I hear the books. Not with my ears, but in my imagination. Maybe the voices camp in the library because the written words hold them there. Maybe they are captives with no place else to go.”

Almost Browne, a native philosopher, always heard more than the voice of the author in a book. He heard the traces of dream songs, the seasons of hearsay, and the crowds of natives who created, enhanced, and mocked the books in libraries.

Almost was born in the back of a rickety station wagon almost on the White Earth Reservation. Almost “signed and inscribed books in the name of Jesus Christ, Vine Deloria, Crazy Horse, Geoffrey Chaucer, and William Shakespeare” in the trickster novel Chair of Tears. “Many book buyers were curious about the native publisher from the reservation. Where did he learn how to read, write, and publish books?

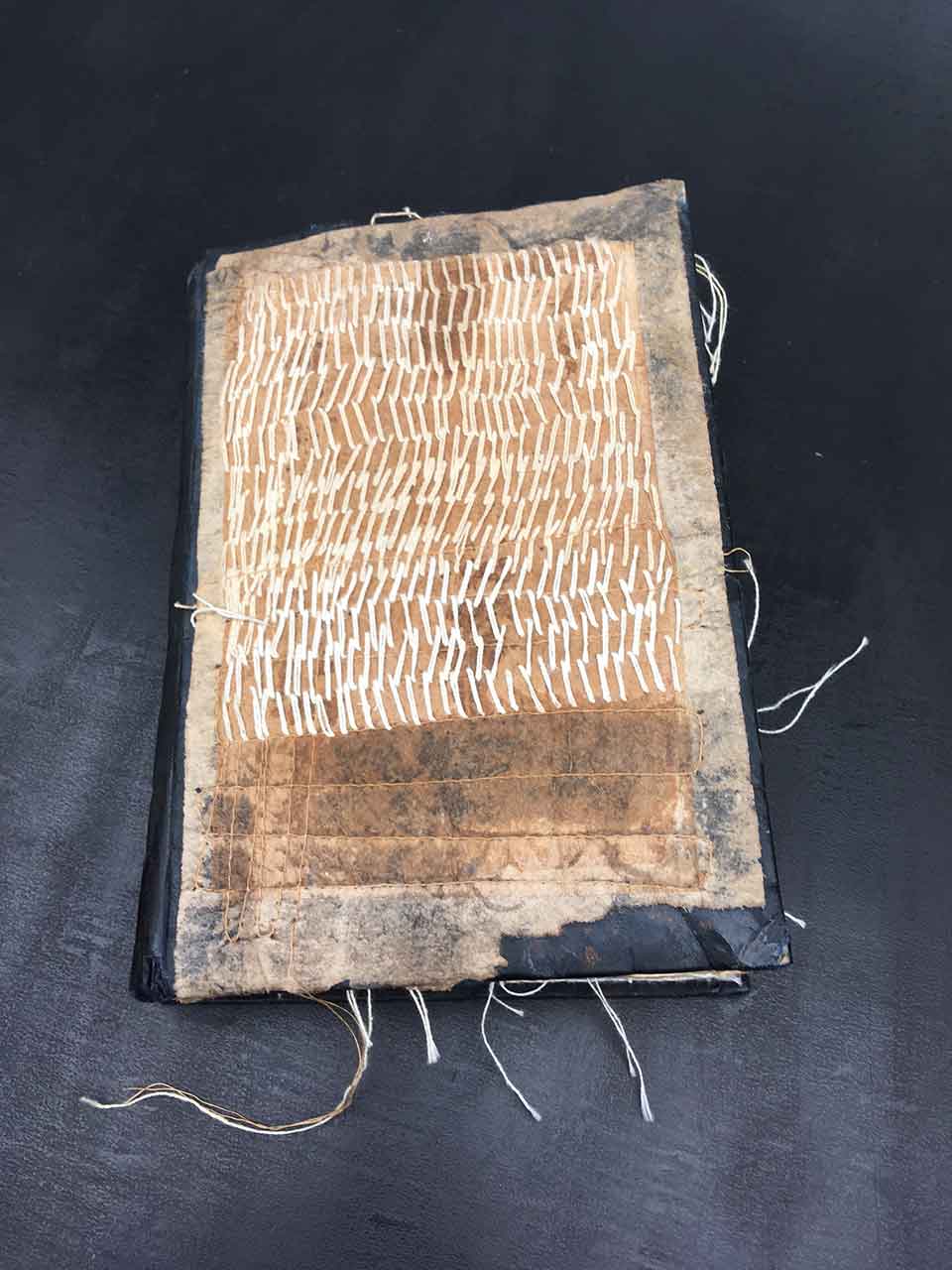

“Almost told his loyal customers at the university that he learned how to read on his own, from the actual books that had been burned in a fire at the Nibwaakaa Library. The few books rescued from the ashes were burned on the sides and the corners. Almost saved copies of burned books and learned to read from the centers of the books. He envisioned the burned words and imagined native stories from the absence of words, from the words that had burned in the fire.”

The metaphors of the book as a personal world of breath, rest, riddle, voices in a library, and creative margins of burned books are a necessary resemblance to native dream songs, a sense of presence in the expansive scenes of natural motion, and the traces of ironic stories. “Summer in the spring,” and “the sky loves to hear me sing” and “overhanging clouds echo my words with a pleasing sound” are invitations to a world of natural motion in the Anishinaabe dream songs recorded by Frances Densmore, a musicologist, more than a century ago. The native singer listened to the turns of the seasons and created a visionary account of a world that would become memorable scenes and stories later published in books. Natives are in the book, and in the breath and voices of the books in libraries.

Native American authors traced the dream songs and stories of earthly creation, totemic associations, figures of ironic transformation, and unfeigned persistence over thousands of seasons, and then created a new world of books, the crucial books of presence, resistance, survivance, and liberty.

Native American authors created a new world of books, the crucial books of presence, resistance, survivance, and liberty.

Samson Occom, William Apess, Joseph Brant, George Copway, and many other natives were tutored at colonial missions before the American Revolutionary War. They became the first natives of the book and created an unmistakable literature of resistance and survivance as exiles in eighteenth-century situations of theocracies, colonialism, and the desolate separatism of a constitutional democracy.

“The outbreak of the American Revolution took many Native Americans by surprise,” observed Colin Calloway in The World Turned Upside Down: Indian Voices from Early America. Natives in the eastern woodland “held tribal land in common, although individuals had personal property and sometimes kin groups had stronger claims to certain lands,” but colonists “insisted on owning the land.”

Natives “made great sacrifices and suffered great losses as a result of the American Revolution,” observed Calloway. The miseries of the revolution “represented another step toward the loss of their freedom. At the end of the war, the British and the Americans signed the Peace of Paris, ignoring the Indians who had been their allies and their enemies. Britain handed Indian lands to the United States and left Indian people to confront the renewed American assault on their land and culture.” The world was “crumbling around them,” and some natives “sought solace in the new religions” and worked with “missionaries and ministers among their own people.”

Samson Occom, a Mohegan minister and schoolteacher, published A Short Narrative of My Life in 1768. He was critical of colonial domination and the exploitation of native missionaries by the church.

Joseph Brant, the mission-educated Mohawk, conveyed a sense of resistance and survivance in his censure of the American Revolution, and sought to secure the redress of land in his speech before Secretary of State Lord George Germaine in London on March 14, 1776. “Brother, in that engagement we had several of our best warriors killed and wounded, and the Indians think it very hard they should have been so deceived by the white people in that country; many returning in great numbers, and no white people supporting the Indians. . . . The Mohawks, our particular nation, have on all occasions shown their zeal and loyalty to the great king, yet they have been very badly treated by his people in that country.”

“I felt convinced that Christ died for all mankind—that age, sect, color, country, or situation make no difference,” wrote William Apess in A Son of the Forest: The Experience of William Apes, A Native of the Forest, first published in 1829. Apess, a Pequot missionary, “seems to have been the first Native American to publish his autobiography; he was assuredly the first to create such a substantial body of publications,” wrote Barry O’Connell in the introduction to A Son of the Forest and Other Writings by William Apess.

Apess wrote that it has been “considered as a trifling thing for the whites to make war on the Indians for the purpose of driving them from their country and taking possession thereof. This was, in their estimation, a right, as it helped to extend the territory and enriched some individuals. . . . Suppose an overwhelming army should march into the United States for the purpose of subduing it and enslaving the citizens; how quick would they fly to arms, gather in multitudes around the tree of liberty, and contend for their rights with the last drop of their blood. And should the enemy succeed, would they not eventually rise and endeavor to regain liberty?”

The Life, Letters and Speeches of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh, by George Copway, an Anishinaabe missionary, was first published in 1847. “The white men have been like the greedy lion, pouncing upon and devouring its prey. They have driven us from our nation, our homes, and possessions,” declared Copway. “Is it not well known that the Indians have a generous and magnanimous heart? I feel proud to mention in this connection, the names of a Pocahontas, Massasoit, Skenandoah, Logan, Kusic, Pushmataha, Philip, Tecumseh, Osceola, Patelesharro, and thousands of others. Such names are an honor to the world!”

“And what have we received since, in return?” asked Copway. “Is it for the deeds of a Pocahontas, a Massasoit, and a host of others, that we have been plundered and oppressed, and expelled from the hallowed graves of our ancestors? If help cannot be obtained from England and America, where else can we look? Will you then, lend us a helping hand; and make some amends for past injuries?”

Copway published The Traditional History and Characteristic Sketches of the Ojibway Nation in 1851, the first cultural history about the Anishinaabe in English. The Minnesota Historical Society published the History of the Ojibway Nation, by William Warren, in 1885, the second and most celebrated history of the Anishinaabe.

Wynema: A Child of the Forest, by Sophia Alice Callahan, was published in 1891 in Chicago, the first novel by a native woman. Callahan and hundreds of other natives are in the book, and in the world of the book, an astute literary presence that can never be denied in the history of books. Luther Standing Bear, Zitkala-Ša, Chauncey Yellow Robe, Charles Alexander Eastman, Carlos Montezuma, Simon Pokagon, and many other natives published books and essays in magazines during the Progressive Era. D’Arcy McNickle, John Joseph Mathews, John Oskison, and others published books during the Great Depression. Countless native authors have published histories, novels, poetry, critical literary essays, and speculative fiction since the 1960s.

Printed books are ready to be discovered in bookstores and in personal and public libraries. Digital books are convenient copies in the air and depend on the close attention of engineers, the distribution of electrical power, internet sponsors, certain politicians, and corporate executives with more interest in pixels than experience as book editors or publishers. The digital reprints of newspapers and rare books are critical to scholars for easy access and research. The Progress and The Tomahawk, for example, two independent newspapers published by my relatives on the White Earth Reservation, are available online by the Library of Congress.

The printed book has a sense of presence, the perception that the author created the scenes and events, not merely a stream of ebooks transmitted on the internet. The printed book is a heart story of memories, the reminiscence of first books, and the books that found readers in libraries and in other situations that are memorable. Books proposed on the internet are calculated and selected by algorithms, not by librarians or readers in a bookstore. Printed books have a presence, new, worn, marked, and abused, and a history of readers is in the books.

Printed books have a presence, new, worn, marked, and abused, and a history of readers is in the books.

The Red Pony, by John Steinbeck, for instance, found me in a public library at age seven. God’s Little Acre, by Erskine Caldwell, censored by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and banned as pornographic in Saint Paul, Minnesota, found me at age thirteen at a drugstore book-and-magazine stand in Minneapolis. Killers of the Dream, by Lillian Smith, found me at age eighteen in a military library on the USS Sturgis on the Pacific Ocean. A Stone, a Leaf, a Door and Look Homeward, Angel, by Thomas Wolfe, found me at age nineteen in a military library at Hokkaido, Japan. Zorba the Greek and The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, by Nikos Kazantzakis, found me as a sophomore college student in the dank basement of McCosh’s Book Store in Dinkytown near the University of Minnesota.

These memorable books were published before the internet and digital books, and yet none of these books, and hundreds more in my memory of bookstores in Minneapolis, Berkeley, Santa Fe, New York, London, and elsewhere, would ever find me now at an online bookstore, and certainly not with a sense of a personal history of books.

Edmond Jabès created his books after the Nazi Holocaust, “after the disaster,” and with a “negative inspiration.” Jabès, a Jew exiled from Egypt after the Suez Crisis, died in Paris, France, in 1991 at age seventy-eight. “There are few contemporary writers who on philosophical, religious and writerly matters would be more quotable than Jabès,” observed Matthew Del Nevo in “Reading Edmond Jabès.”

“Today a sense of trust is doubted by an all-consuming sense of distrust,” noted Del Nevo. “We know that it is not reasonable to expect anything at all from others. And yet, we hope—though something gnaws at the core of this hope, reminding us that the thread has been cut. . . . Jabès inaugurates a form of literary debris appropriate to a transit time. Here, in the aftermath, in this desperate situation, this desolate place, Jabès and we ourselves, if we are to understand him, are beginners. Only we cannot be sure quite what has ended and what is to be begun.”

Native Americans created books after the spread of lethal pathogens, created perceptive dream songs after the greedy fur trade and slaughter of totemic animals, and created ironic stories after the removal to reservations and the cause of separatism in a constitutional democracy. Natives endured the torments of enlightenment, mocked the academic censors and couriers of shame, and at last created the books of survivance and liberty.

The future of the book is the past, in the torment of memory and literary debris, and even so that elusive sense of torment overcomes the pretense of digital erudition and the death of reason on the internet with irony and reminiscence of an actual book in hand.

Minneapolis, Minnesota