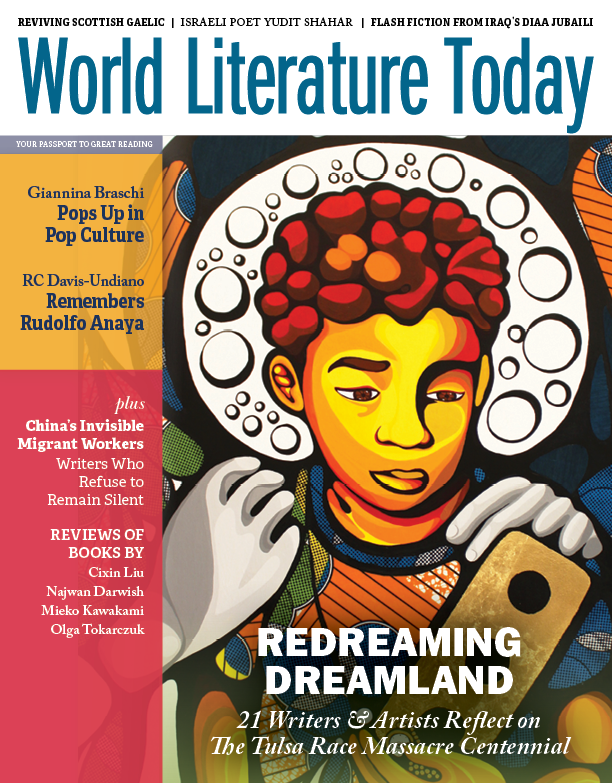

Photographing the Tulsa Massacre: A Conversation with Karlos K. Hill

Just published by the University of Oklahoma Press, The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre: A Photographic History represents a landmark work of historical scholarship. Historian Karlos K. Hill spent three intensive years researching and writing the book. I had the privilege of reading an advance copy and reached out to Dr. Hill to initiate a dialogue about his work on the project.

Daniel Simon: You write that “photographing brutal acts of anti-black violence had become an important social ritual in early twentieth-century America.” Coincidentally, photography became widely popular in the 1910s with the advent of affordable 35mm cameras, which were marketed to the general public to coincide with the rise of the tourism industry as a national pastime. Yet as “one of the most photographed episodes . . . of anti-black violence in American history,” the site of the Tulsa Race Massacre remains a century-old crime scene. As a visual historian, how would you like readers in 2021 to view the massacre as a photographed event, especially in the context of lynching culture and its prevalence during the Nadir of American race relations (ca. 1877–1923)?

Karlos K. Hill: Without the photos of Greenwood’s destruction, I believe it would be more difficult to convince people now of the scale of violence that took place. While not their intention, white Tulsans who snapped pictures of Greenwood’s destruction made it possible for future generations to bear witness to what occurred. To a degree, visual evidence of Greenwood’s destruction stands in for so many other instances of racial terror that were not visually recorded and subsequently forgotten.

Visual evidence of Greenwood’s destruction stands in for so many other instances of racial terror that were not visually recorded and subsequently forgotten.

Simon: You also write about your “deep desire to write a book that would highlight the perspectives of the black survivors.” Yet much, if not most, of the photographic history of the massacre represents the gaze of white Tulsans. How did you go about reconciling that discrepancy?

Hill: In writing this book, it was important for me to prominently feature Black survivor testimony in ways that disrupted and recontextualized the white gaze embedded in the vast majority of photos exhibited in the book. Doing so was all the more important because many of the images were inscribed with racist comments. While the white gaze is never completely silenced, I think inclusion of Black testimony alongside the images creates a powerful counternarrative.

Simon: One of the most horrific aspects of the massacre is that white perpetrators used technologies of war—which had been perfected in the so-called Indian Wars of the late nineteenth century, the Spanish-American War, and World War I—against Black American citizens: machine guns, assault-style military rifles (including bayonets), airplanes dropping incendiary bombs, and trucks that could speed groups of armed mobs into Greenwood. Survivors were also “herded like cattle” into euphemistically named “detention centers” afterward, ostensibly for their own protection. Yet white spectators casually observed the destruction of Greenwood as if attending a matinee and even brought shopping bags with them to carry off stolen property. Was that also an effect of lynching culture’s ability to desensitize onlookers to mass spectacles of anti-Black violence?

Hill: Quite frankly, many white Americans accepted lynching and other forms of anti-Black violence as a “necessary evil.” Lynching culture’s primary function was to rationalize white Americans’ brutal repression of Black people as legitimate, even commonsensical. At the height of lynching during the 1890s, a Black person was lynched every three days on average. Because the lynching of Black people became both routine and uncontroversial for white Americans during the lynching era, even spectacular acts of anti-Black racial violence such as the race massacre were deemed acceptable.

Simon: I was struck by Dr. P. S. Thompson’s description of the aftermath of the massacre—namely, the white looting and arson of Black-owned businesses and homes in Greenwood—as the “unthinkable, unspeakable climax” to the events of May 31 and June 1. The ensuing cover-up and historical erasure of the massacre were also unthinkable, but the photographs confront anyone who sees them with the inescapable brutality of the event. A century afterward, they “speak” to us in ways that mere words cannot. Pedagogically, what do you hope teachers and students learn from your book?

Hill: When I decided to pursue a pictorial history of the race massacre, my main goal was to provide an arresting visual record of what occurred in the interest of making the case emphatically that what occurred was a race massacre rather than a riot. For teachers and especially students who might read the book, I hope the images make it possible for them to develop a deeper emotional connection to the story and to individual survivors of the massacre.

Simon: Chapters 3 through 5 document the heroic resilience of Black Tulsans who set up tents amidst the rubble and almost immediately began to raise up the Greenwood community from the ashes. “Angels of Mercy” (chap. 3) tells the remarkable story of the American Red Cross’s efforts, which helped more than 8,500 survivors get back on their feet. I was struck by the fact that seven churches had been rebuilt by December 30, 1921 (fig. 5.12). According to Rev. Dr. Robert Turner, the current pastor of Historic Vernon AME Church on North Greenwood Avenue, parishioners went back to church the next Sunday, just four days after the massacre, having been “refined by fire.” Could you talk about the role of Black churches—and the importance of belief in general—in rebuilding Greenwood?

Hill: Black churches (particularly Mt. Zion and Vernon AME) were looted and burned by the rampaging white mob. As photos in my book illustrate, Greenwood’s Black churches were some of the first buildings to be rebuilt. I believe Greenwood’s Black churches sought to quickly reestablish themselves so that they could provide much-needed assistance and support to their destitute congregants. Due to the leadership that Black churches played in providing emergency relief, the idea that survivors could remain in Tulsa and rebuild became a viable possibility.

Simon: Returning to the question of representing Black survivors’ perspectives, their written and oral testimonies in chapter 6 provide an overwhelming portrait of courage and resilience in the face of such terror. The sheer humanity of their stories stands in stark contrast to the gut-wrenching devastation depicted in the photographs of chapters 1 and 2. What prompted you to include their perspectives?

Hill: My photographic history is dedicated to the lives and legacies of race massacre survivors. Without their grit and determination, there would be little to commemorate on the hundredth anniversary of the massacre. It was important to me to share their perspectives on what occurred because for so many years their accounts were either ignored or discredited. Weaving their survivor narratives throughout the book and especially in chapter 6 was meant to make their stories central to the story, as they should have been all along.

Weaving survivor narratives throughout the book was meant to make their stories central to the story, as they should have been all along.

the destruction of her home /

Courtesy of the Ruth Sigler Avery Collection –

Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921,

Department of Special Collections & Archives,

Oklahoma State University–Tulsa

Simon: In the epilogue, you write about justice for the victims and survivors of the massacre being “too often permanently deferred.” Beyond your book, what can the occasion of the centennial offer to help the Greenwood community achieve justice?

Hill: Reparations for survivors and descendants are crucial for achieving justice. The hundredth anniversary of the race massacre is an opportunity for the City of Tulsa and the State of Oklahoma to do the right thing in regard to reparations. Without a commitment to repair what was taken away, it is not possible for authentic reconciliation and renewal to occur.

Simon: In September 1955, Jet magazine famously published photographs of Emmett Till’s mutilated and mangled body and continued to publish articles about the Montgomery bus boycott and the growing Civil Rights Movement throughout the 1950s and ’60s. Many of the iconic civil rights photographs of the 1960s went on to be published in magazines and newspapers with largely white readerships. What role do you see photography and cultural magazines playing in the current debates about racial justice?

Hill: As I have tried to frame the history of the race massacre through photos, I hope magazines and other cultural outlets will follow suit because race massacre photos (combined with survivor accounts) tell a compelling, even unforgettable story of death, destruction, and rebirth. I hope that magazines such as WLT can amplify and disseminate widely the story I’ve tried to tell in the photographic history.

January 2021

An excerpt of this interview also appears in the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of Oklahoma Humanities. To get a free copy of the issue, visit okhumanities.org.

Karlos K. Hill is an associate professor and chair of the Clara Luper Department of African and African American Studies at the University of Oklahoma. His other books include Beyond the Rope: The Impact of Lynching on Black Culture and Memory (2016) and The Murder of Emmett Till (2020). He also serves on the steering committee of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission.

Karlos K. Hill is an associate professor and chair of the Clara Luper Department of African and African American Studies at the University of Oklahoma. His other books include Beyond the Rope: The Impact of Lynching on Black Culture and Memory (2016) and The Murder of Emmett Till (2020). He also serves on the steering committee of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission.