Undreaming Dreamland

How sweet it were, hearing the downward stream,

With half-shut eyes ever to seem

Falling asleep in a half-dream!

—Alfred Lord Tennyson, “The Lotos-Eaters”

Dream is such a beautiful, multifaceted word, at once noun and verb; we use it in English to mean so many things: we dream the impossible dream, urge our children to dream big, follow their dreams, dream of a better tomorrow, chase the American Dream. Dreamlike and dreamy are gauzy, evocative adjectives, dreamily a lovely adverb.

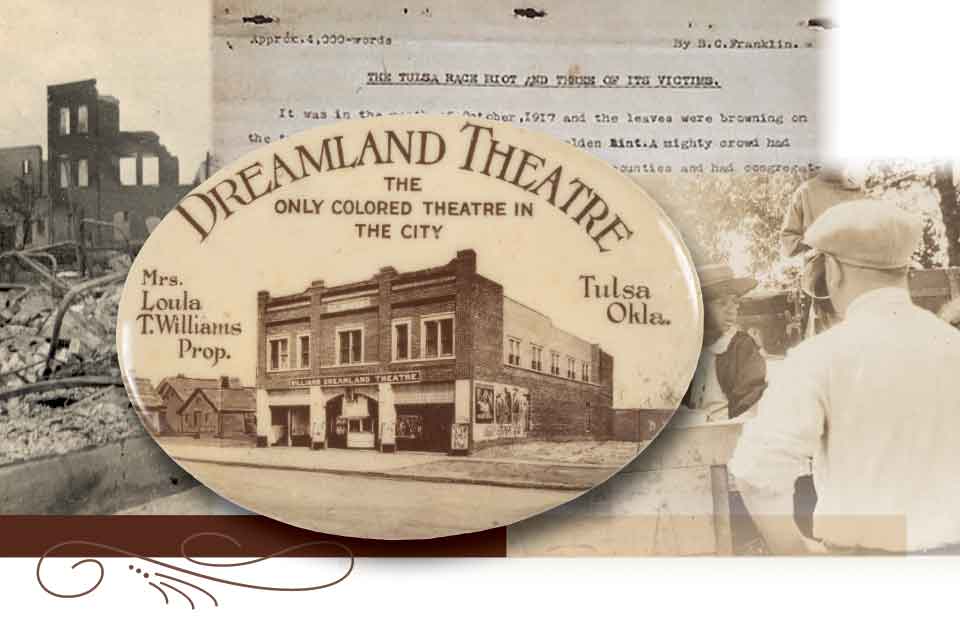

Dreamland is different. It evokes a kind of daydream illusion, a waking dream. It was the name of one of the two movie theaters destroyed in the 1921 white terrorist assault on Greenwood. The other theater, white owned, was called the Dixie. Consider a moment: a white-owned movie theater in the heart of the segregated Black district named after that romanticized nickname for the Old South, where chattel slavery was the engine of white commerce and wealth. This says much we ought to know about the white climate in Tulsa at the time of the massacre.

But the Dreamland Theatre at 127 North Greenwood was owned and operated by a Black entrepreneur, Loula Williams, who, along with her husband, John, created in Oklahoma their piece of the American Dream. They also owned Dreamland theaters in Okmulgee and Muskogee, but the Dreamland in Tulsa, which seated 760 and showed live musical and theatrical revues as well as silent films, was the crown jewel. Emblematic of the successes of Black Wall Street, the Dreamland Theatre has come to symbolize the wealth and prosperity in Tulsa’s Greenwood community before the assault—and the smoking ruins afterward.

The word dreamland is also a metaphor for how the American film industry—in its nascency in 1921— forged a dream of this country: a manufactured illusion reinforcing the master narrative of what America believed itself to be. The movies gave us a vision of white Klan terror as justice in D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, which was screened at the White House only five years before the massacre; the rugged individualism of the westerns, where indigenous peoples were inevitably portrayed as bloodthirsty “savages”; and the glittering wealth and beauty of the privileged class, a dream that would reach its apotheosis in the 1930s, when Americans of all races were standing in soup lines and dying from dust pneumonia.

In his 1957 story “Sonny’s Blues,” James Baldwin speaks of young boys growing up in midcentury Harlem knowing only two darknesses: “the darkness of their lives, which were now closing in on them, and the darkness of the movies, which had blinded them to that other darkness, and in which they now, vindictively, dreamed . . .”

In 1921 Tulsa, the future promised to be different for young African Americans growing up in Greenwood. At the Dreamland, they could believe a certain dream, imagine a promise fulfilled, until those chaotic hours of May 31 and June 1 when the dream was crushed—and not crushed only but devastated, annihilated, burned to ash, ground to dust by white rioters in just such a determined way as to teach the citizens of Greenwood, and by extension all Black Americans: this is what happens when you dream. Or rather, this is what happens when you work to make a concrete reality of your dreams.

For white Americans—for this white American, anyway—dreamland offers other connotations. I think of the myriad illusions and delusions of whiteness in the American dreamland where I grew up, just fifty miles north of Tulsa, never having heard a word of the massacre, as most white folks in those days never heard. This is surely one illusion in white America’s dreamland: we think we know our history, when whole swathes of it have been, and continue to be, covered in silence, obfuscation, and smoke.

Then, too, there is the illusion of the American Dream. It is a lie now. It was a lie then.

Then, too, there is the illusion of the American Dream: our grand notions of democracy, liberty, equality, opportunity for prosperity through hard work regardless of race, class, or circumstances of birth. It is a lie now. It was a lie then. And we believed the lie unspoken: that Black folks were not worthy to be a part of that dream. No one said it in words, not to us white seventh-graders riding our school bus through the segregated Black district of poverty and separation in our town. We were kept ignorant of the fires in Greenwood that rolled north across the prairie decades earlier, scorching away all hope of Black prosperity, peace, safety from white violence—it was not to be. Not in our town, or any town, not in this white-dominated America. We were so segregated, so indoctrinated, there was a permeation of bias and prejudice so invisible and complete, it was like the air we breathed.

Yet I listened to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, my heart lifting with the soaring cadences, and somehow believed his dream was our dream. I heard: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

What I did not hear—did not have ears to hear—was his other promise: “And there will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.”

I heard: “I have a dream that one day . . . little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers”

and did not hear the words inside the ellipsis:

“. . . down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, one day right there in Alabama . . .”

My mind could receive only the illusions I’d been taught. All men are created equal. Certain unalienable rights. Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

This dream is only one part of our dreamland, but it is foundational, and I was well into young adulthood before I began to see the lie at the heart of it. For many years I called it as I saw it and lived it: “the presumptions of whiteness.” These days I call it by its more telling name: white supremacy. This is the dream that has to be undreamt.

To do that, of course, we have to first come awake, and that’s not so easy to do in this American dreamland. For me it has been a slow, groggy process, beginning in the Civil Rights Era of my youth and continuing through the racial unrest in 1980s New York, where I’d moved in my twenties and where I first learned about the Tulsa Race Massacre while reading a biography of Black writer Richard Wright. Immediately I began research for a novel about the massacre, and this is one powerful place where awakening began for me as I read in blunt, direct language the overt anti-Black racism in the white newspapers of the day. I learned for the first time that they were, in fact, white newspapers. I had thought them merely “the newspapers,” until I read in Oklahoma’s Black Dispatch and Tulsa Star and the NAACP’s The Crisis and other Black journals a reality I’d had no inkling about. These contrasting visions have informed everything I’ve written since—not just the novel about the massacre, Fire in Beulah, but all my novels and nonfiction. It permeates everything I write because it permeates everything in America.

I think of African Americans who live the nightmare of that dreamland in ways I’ll never live it, nor completely imagine it, though I have to try, as we all have to try, those of us who dwell in America’s white dreamland enjoying its privileges, benefits, unacknowledged illusions. I think of white Americans who are trying to come awake in this season of our so-called national reckoning on race—I say “so-called” because I am not sure that it is a true reckoning. I want to believe it is, that we’re making a true accounting of our sins past and present, but I also know that white demonstrations and discussions and book-club readings may turn out to be another daydream allowing us to go on believing our goodness dream of America. How tricky it is to know one is dreaming in dreamland. And history, my own and the nation’s, tells me how hard it is for white folks to come awake.

And history, my own and the nation’s, tells me how hard it is for white folks to come awake.

Even for the many who are really trying, it seems nearly impossible. With every shaking hand on the shoulder, every heart’s cry, wake up wake up!, from Mother Emanuel Church to the killing of George Floyd, reality calls to us, and groggily, with a kind of dazed yearning, we are trying to come around. Maybe, like Homer’s lotus eaters, we need an Odysseus to capture us and truss us and pull us, weeping and wailing, away from the land of the waking dream.

I’ve wondered if the January 6, 2021, white mob assault on the Capitol could be our Odysseus. But then I consider the similarities between that assault and the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, which surely shook the nation when it happened, and afterward—by unspoken collusion in dreamland—disappeared from our history. I take it for a warning. How powerful is the lotus, how insidious our willful forgetting.

How do we recognize this horror, which for so long we kept hidden?

So now we come to the centenary of the 1921 white terrorist assault in Tulsa, and I ask myself, What is our place in the commemoration, we Americans who, in the words of James Baldwin and others, believe we are white? How do we recognize this horror, which for so long we kept hidden? How do we acknowledge that we are the authors, both intentional and incidental, of that riotous conflagration one hundred years ago when the dream of white supremacy annihilated the dream of Black Wall Street? How do we own it and yet not try to take ownership of it, not try to make it somehow about us, as we are so inclined to do? For myself, I think of a few possible paths forward:

To learn more. Although I’ve been studying the events of the Tulsa Race Massacre and its aftermath for thirty years, when it comes to America’s race story, there is always, always more to know.

To listen to the voices of those who have suffered the violence, theft, and death, then and now.

To surrender the narrative to those who endured it and daily endure the anti-Black racism at the heart of this country—except for the parts I can know, the parts I must recognize, and render: the white illusions that tell me America’s promise of equality and justice is a true thing.

To own my part in the collective dreamland.

To wake up.

The collective is only changed, finally, individually. Person by person. Dream by dream.

How do we do that? America’s white-supremacist dream is a collective dream in a collective dreamland, and so it will have to be undreamt collectively. But the collective is only changed, finally, individually. Person by person. Dream by dream. Black artists and activists are way ahead of white dreamers on this one; they’ve already envisioned the new world, they’re already creating it—as are indigenous and other artists and activists of color. For the rest of us, though, maybe the question is how do I do it? What’s my part? I don’t have simple answers, I just know we have to be willing to risk it: risk knowing what we don’t know, and unknowing what we think we do. Risk asking ourselves: What, precisely, do I lose if I lose that dreamland? Am I willing to risk that? If we are, then, yes, I believe that’s a place to begin.

University of Oklahoma