In Search of a Lost Poet: Marcelo Ensema Nsang

Going behind the scenes of WLT’s September issue, poet, translator, and documentary filmmaker David Shook talks with Brian Hewes about making his new documentary, Kilometer Zero, a journey that began in police detention in Malabo.

Brian Hewes: I’m interested in the genesis of Kilometer Zero—it’s not the type of project just anyone comes up with. Where did you hear about poet Marcelo Ensema Nsang?

David Shook: Well, I started translating Marcelo’s work while I was in Burundi for the summer, working, in 2010. I’d spend a lot of my free time writing and translating, and at the time I was mostly working on Mexican prose poems. But being in Africa, I had this recurring question nagging me—Why don’t you translate something African? As a Spanish speaker, I had long had a casual interest in the country of Equatorial Guinea, though I knew very little about its present political state, and I found an anthology of poetry from the 1970s that had been digitized. Marcelo was the first Guinean poet whose work really grabbed me, and I started translating it immediately, that evening in Burundi.

BH: What made you decide to find him?

DS: Marcelo’s story, even in the thumbnail portrait of the anthology, is a large part of what compelled me to continue translating him, and a part of what made me want to meet him. Having been incarcerated and tortured under the Macías regime really captured my imagination. I like to think I have a healthy skepticism of political poetry—the frequent superficiality of its political concerns. But Marcelo’s poetry exudes something else, a deeper engagement with what it meant to be human and, I think, what it meant to be a moral person. His story resonates with my own history. I’m the son, grandson, and nephew of pastors—heir to the cloth—and Marcelo has been a Claretian priest for the entirety of his adult life. That’s actually why he hasn’t managed to publish a complete collection—yet. He’s been too busy. But he hasn’t stopped writing poetry, whether he’s been in jail or in the monastery. And while I don’t have any plans to follow in my family’s vocational footsteps, his experience in that world resonated with me in a special way.

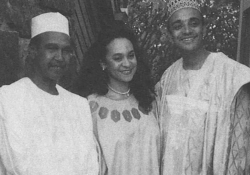

The actual decision to find him seemed pretty ridiculous. It was just a fantasy of mine, especially after I was disqualified for an NEA Translation Grant because of my lack of copyright permission. (Who would have thought that a country without bookstores or libraries would be a signatory to the Berne Convention, which grants authors eighty years of posthumous copyright!?) The night I found out I was disqualified, I was drinking a beer with my friend Jon Worley, a TV writer, and my wife, Syd, who is also a writer. And instead of telling me how stupid I was, to want to penetrate what’s pretty much a police state, where it’s illegal to take photographs without government permission, they said, “Let’s do it.” Two weeks later we were in Malabo.

BH: What was that like? Did you encounter any problems on the ground?

DS: We were detained well after midnight by the commissioner of police in a room with blacked-out windows, a story I’ve recounted in an essay for AMBIT and now available for Kindle. It freaked me out. But we told the truth, without the camera, and we made it through. Our purpose was too ridiculous to be a lie: I’m looking for an obscure Guinean poet because his work so resonates with me. Actually, being detained let us slip through without going through customs, which enabled us to get our equipment in.

Once we were on the ground, we were taken in by a community of young Guinean artists. They took care of us, showed us a good time, and gave us a glimpse into the everyday life of a Guinean citizen—a citizen not related to Obiang, that is. On one particularly memorable night, we were invited to a party to celebrate the birth of a baby—the one that features at the end of the trailer, actually. It was a beautiful experience, one that filled me with hope, an unnatural impulse on the face of things, considering the dearth of opportunity under Obiang’s three-decade rule of the country. Despite being in a small room of zinc and cinder, lit only by candles and without running water, we celebrated the bright future of a country whose people are its greatest resource. That’s something that was important to me to show in the film: that no matter what difficulties its people face, no matter how insurmountable they seem when countries like ours are unwilling to sacrifice their commercial stake in them, Equatorial Guinea is a place of exceptional human beauty.

David Shook’s translations of verse by Marcelo Ensema Nsang and two other Equatorial Guinean poets appear in WLT’s September 2012 issue. Follow the progress of Shook’s film Kilometer Zero—including up-to-date information on where to see it screened near you—at http://kilometer-zero.com or http://davidshook.net. Learn more about his experience in Equatorial Guinea, and the country’s political situation, in Detained at Kilometer Zero, available for Kindle.

Brian Hewes studied business at the University of Oklahoma. He serves as digital marketing manager for the Los Angeles Review of Books and managing editor of Molossus. In addition to the many literary and visual arts events and projects he produces, Hewes reviews contemporary philosophy. He lives in Los Angeles where he manages Phoneme and Ricochet Books.