A Swedish Poet in Oklahoma: Remembering Tomas Tranströmer

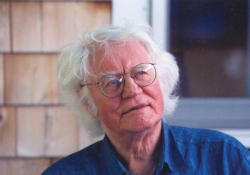

When news broke late last week that Nobel Prize laureate Tomas Tranströmer had died in Stockholm on March 26 at the age of eighty-three, the editors and staff of World Literature Today joined the rest of the world in celebrating the legendary writer’s life and work, even as we mourned his passing. This year marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of Tranströmer’s visit to the University of Oklahoma to accept the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, an event commemorated in the Autumn 1990 issue of WLT. Contributors to that issue included Estonian poet and philosopher Jaan Kaplinski (who nominated Tranströmer for the Neustadt Prize), poet and translator Rika Lesser, and 1978 Neustadt laureate Czesław Miłosz, who translated three of Tranströmer’s poems from English into Polish for the issue. In a note to the poems, Miłosz wrote: “I give myself the privilege of roaming through world literature in search of a spark which would ignite one more poem of mine, be it labeled ‘translated from.’ . . . As a ‘biased’ reader of Tranströmer in English, I am particularly sensitive to those poems of his which let me see, in a flash, a fragment of the visible world.” The “Oklahoma” poem below was written years before Tranströmer’s 1990 visit, and the laureate’s brief words of acceptance for the Neustadt Prize follow. – Daniel Simon, Editor in Chief

Oklahoma

Tomas Tranströmer

I

The train stalled far to the south. Snow in New York,

but here we could go in shirtsleeves all night.

Yet no one was out. Only the cars

sped by in flashes of light like flying saucers.

II

“We battlegrounds are proud

of our many dead . . .”

said a voice as I awakened.

The man behind the counter said:

“I’m not trying to sell anything,

I’m not trying to sell anything,

I just want to show you something.”

And he displayed the Indian axes.

The boy said:

“I know I have a prejudice,

I don’t want to have it, sir.

What do you think of us?”

III

This motel is a foreign shell. With a rented car

(like a big white servant outside the door).

Nearly devoid of memory, and without profession,

I let myself sink to my midpoint.

1966

Translated from the Swedish

By May Swenson

Editorial note: From Windows & Stones: Selected Poems. Copyright © 1972 by the University of Pittsburgh Press. Reprinted in World Literature Today 64, no. 3 (Summer 1990), 436.

* * *

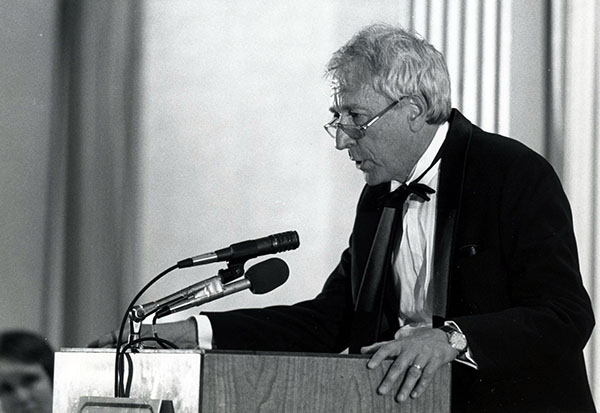

Laureate’s Words of Acceptance

by Tomas Tranströmer

My warm thanks to World Literature Today, the unique magazine with its visionary editor, to the University of Oklahoma, and to the Neustadt family, which with rare generosity has taken on the task of lending literature a helping hand.

I want to draw attention to a fairly large group of men and women who share this prize with me, without getting one single cent: those who have translated my poems into different languages. No one mentioned, no one forgotten. Some are my personal friends; others are personally unknown to me. Some have a thorough knowledge of Swedish language and tradition, others a rudimentary one (there are remarkable examples of how far you can get with the help of intuition and a dictionary). What these people have in common is that they are experts in their own languages, and that they have translated my poems because they wanted to. This activity has brought them neither money nor fame. The motivation has been interest for the text, curiosity, commitment. It ought to be called love—which is the only realistic basis for poetry translation.

Let me sketch two ways of looking at a poem. You can perceive a poem as an expression of the life of the language itself, something organically grown out of the very language in which it is written—in my case, Swedish. A poem written by the Swedish language through me. Impossible to carry over into another language.

Another, and contrary, view is this: the poem as it is presented is a manifestation of another, invisible poem, written in a language behind the common languages. Thus, even the original version is a translation. A transfer into English or Malayalam is merely the invisible poem’s new attempt to come into being. The important thing is what happens between the text and the reader. Does a really committed reader ask if the written version he reads is the original or a translation?

I never asked that question when I, in my teenage years, learned to read poetry—and to write it (both things happened at the same time). As a two-year-old child in a polyglot environment experiences the different tongues as one single language, I perceived, during the first enthusiastic poetry years, all poetry as Swedish. Eliot, Trakl, Éluard—they were all Swedish writers, as they appeared in priceless, imperfect, translations.

Theoretically we can, to some extent justly, look at poetry translation as an absurdity. But in practice we must believe in poetry translation, if we want to believe in World Literature. That’s what we do here in Oklahoma. And I thank my translators.

Norman, 12 June 1990

From World Literature Today 64, no. 4 (Autumn 1990), 552–53.