Perspectives on Walking: A Lit List

In the summer of 2022 I (James Fawcett) walked from Denver to Durango on the Colorado Trail. I started the walk alone and eighteen years old, having just finished my freshman year of college. On days spent hiking alone under sheets of rain and barrages of lightning, my mental fortitude was tested and I learned to be more grateful for what I had: a trusty tarp that never leaked and knees that could handle running downhill to the safety of the trees. I also learned the true meaning of “hiker trash” during rambunctious days spent with friends in RV parks and motel suites, wearing our cleanest articles of clothing—still quite dirty judging by some of the looks we got—while savoring restaurant meals, before putting up a thumb and getting shuttled back to the woods. On trail, I met remarkable people and tried to absorb myself in the wildflower-laden meadows, harrowing passes, and crystal-blue alpine lakes of the Rocky, Sawatch, and San Juan mountain ranges.

In the summer of 2022 I (James Fawcett) walked from Denver to Durango on the Colorado Trail. I started the walk alone and eighteen years old, having just finished my freshman year of college. On days spent hiking alone under sheets of rain and barrages of lightning, my mental fortitude was tested and I learned to be more grateful for what I had: a trusty tarp that never leaked and knees that could handle running downhill to the safety of the trees. I also learned the true meaning of “hiker trash” during rambunctious days spent with friends in RV parks and motel suites, wearing our cleanest articles of clothing—still quite dirty judging by some of the looks we got—while savoring restaurant meals, before putting up a thumb and getting shuttled back to the woods. On trail, I met remarkable people and tried to absorb myself in the wildflower-laden meadows, harrowing passes, and crystal-blue alpine lakes of the Rocky, Sawatch, and San Juan mountain ranges.

The Colorado Trail is just under five hundred miles long, and I finished it in twenty-two days. Most days I walked well over twenty miles, and I even had a few days that stretched above thirty. The length traversed on any given day wasn’t an issue in and of itself, but, upon reflection afterward, I realized that I was far too focused on finishing the trail rather than being present through it. I was so intoxicated by the idea of coming back and telling people that I hiked five hundred miles in a month that I rarely focused fully on what I was doing—on the beauty and peace that can be found in the simple act of walking.

This inner turmoil has since caused me to investigate how and why I walk. I have tried to shrug off the innate competitive and conquering attitude toward nature that we grow up with in the West in favor of more respectful and pleasant ideals. Now when I walk—whether for transportation, pleasure, or mindfulness—I attempt to remain in the moment and lean into the slow and passive nature of walking in a world so inundated with cars and productivity. This is, of course, a lifelong pursuit that I will probably never master. But every time I find my mind wandering toward the past or the future, I try to nudge it back to the trees and the rhythm of my steps.

Every time I find my mind wandering toward the past or the future, I try to nudge it back to the trees and the rhythm of my steps

Maddie Meyers and I are two of the leaders of a club that puts on backpacking, camping, and hiking trips for students at the University of Oklahoma. As such, we have had many discussions about our approaches to walking: how much to push participants forward when they are tired, how important (or unimportant) summiting is, and simply why we enjoy walking so much. This lit list could never comprehensively cover human perspectives on walking; walking is so fundamental to being human that nothing ever could. However, these books have aided us in broadening our perspectives on walking and bridging the perceived gap between humans and nature. We hope they do the same for you.

Rebecca Solnit

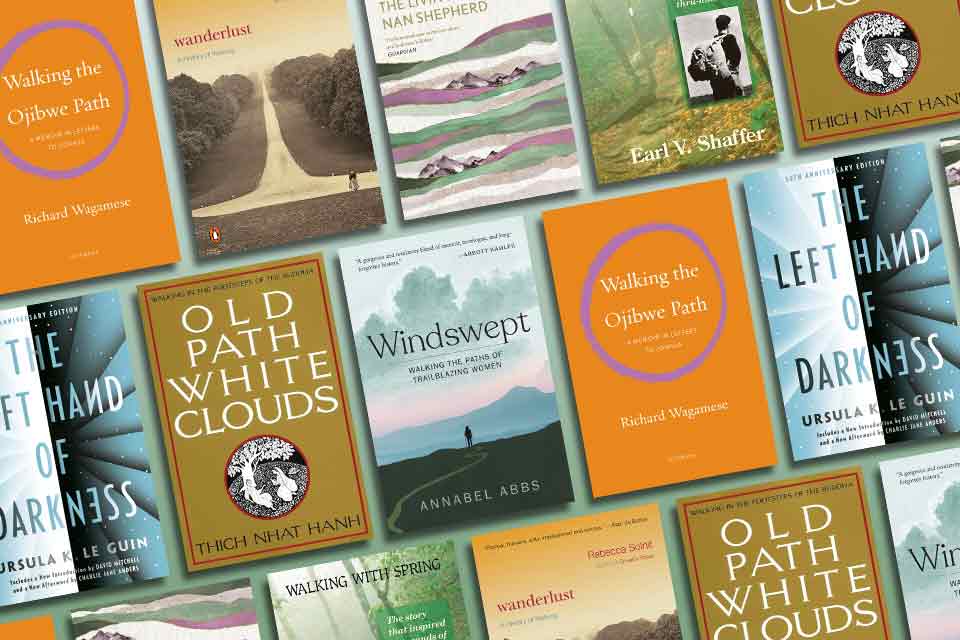

Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Viking, 2000

Wanderlust is a collection of Rebecca Solnit’s writings on walking. The book starts with a discussion of paleontology and the evolution of bipedalism—and the misogynist beliefs that shaped the idea that women walked somehow worse than men from the very beginning. The book continues by slowly touring the evolution of mainstream European and American thought on walking alongside greater philosophical, literary, and historical movements. She explains how the upper class once viewed well-kempt gardens as the ideal place for a stroll before the Romantic era ushered in a new wave of wilderness expeditions, mountaineering, and conservation movements. Then, as the countryside grew more appealing in the industrial age, walking became an act of rebellion for working-class people who trespassed on private land seeking refuge from smoggy cities.

She also explores some of the reasons why people walk: philosophers wandering streetscapes to plunge into the depths of their minds, pilgrims vying for religious or secular fulfillment, socialists finding equality in nature, rock climbers searching for achievement, and sex workers advertising their business and seeking safety in numbers. Wanderlust finishes with a survey of the modern American city, including a reflection on Solnit’s personal walk out of Las Vegas, and the “Suburbanized Psyche.”

While sometimes ignorant of the problematic nature of America’s conservation movements, Wanderlust is an excellent survey of western European and American thoughts on walking.

Annabel Abbs-Streets

Windswept: Walking the Paths of Trailblazing Women

Tin House Books, 2021

In Windswept, Annabel Abbs-Streets retraces the steps of eight different women writers, artists, and activists whose leisure walking habits informed their creative work. She does so by reading their books, journals, and letters, but more importantly by walking where they walked to physically put herself in their shoes. From Simone de Beauvoir in the French countryside to Nan Shepherd in the Cairngorms of Scotland to Georgia O’Keefe in Texas and New Mexico, Abbs-Streets shares her experiences of following the trails left by these women and how, despite the years separating their walks, sharing their spaces brought her closer to them.

As Abbs-Streets explains, women’s walks are often overlooked and minimized; by inhabiting these creators’ physical paths, Abbs-Streets gains new appreciation for how their ideas and experiences resonate in her own life in both body and mind. By turns historical and modern, broadly scientific and intensely introspective, Windswept examines the impacts of walking for pleasure on creative work, well-being, and women’s ability to find their footing in a demanding world.

Thich Nhat Hanh

Old Path White Clouds: Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha

Parallax Press, 1991

In Old Path White Clouds, Thich Nhat Hanh reconstructs the life and teachings of Gautama Buddha through a series of stories. Although the book describes far more than just the Buddha’s walks, the Buddha’s walking meditations were transformative in his quest for enlightenment. Hanh describes how the Buddha meandered up and down rivers and around lotus ponds to clear his mind and find appreciation for the natural world. Walking is also consistently intertwined with the narrative as a mode of transport as the Buddha moves to different homes, towns, and monasteries to help more people on the path of liberation.

The book itself is a meditation with slow, simple, and sometimes repetitive prose. Like many religious texts, a reader can slowly pore through each page or sporadically pick through different chapters within its six hundred pages and still expect to find wisdom, insight, and peace.

Nan Shepherd

The Living Mountain: A Celebration of the Cairngorm Mountains of Scotland

Canongate Books, 2019

The Living Mountain is Scottish nature writer Nan Shepherd’s own answer to the issues of the mountaineering genre. Rather than depicting mountains as a goal to summit and conquer, Shepherd instead meditates on her own experiences hiking in the Cairngorms to examine the mountain as a living, changing entity. Experience and understanding, not higher heights and longer mileage, are the prizes at stake. Alongside memories of her many visits to the mountains, Shepherd dedicates her prose to musings on the particular qualities of the air, rock, ice, and light that comprise them, asking readers to consider what makes their own mountains unique and what qualities they must learn to truly understand a place.

Richard Wagamese

Walking the Ojibwe Path: A Memoir in Letters to Joshua

Milkweed, 2023

In Walking the Ojibwe Path, Richard Wagamese explains how fathers, in a traditional Ojibwe family, are meant to walk their children through the world and explain everything they see. Through rambles across the land, the father should instill a sense of unity in his child by explaining everything’s place in Creation. This ritual would start from infancy, before the child could even understand what their father was saying.

Wagamese was taken from his Ojibwe parents as a child and moved to foster care, so he never fully received this education. Similarly, after bouts with alcoholism and incarceration, he was never able to perform this sacred duty for his child. This memoir is his attempt to reconcile that fact and provide guidance to his then six-year-old son. Wagamese takes us along on his journey through foster care, homelessness, and the ever-present pull of alcoholism. His wisdom is in his trials and his willingness to work on himself after his wrongdoings, even though Canada was ambivalent and sometimes hostile to his needs as an Indigenous man.

A heart-wrenching and touching memoir, Walking the Ojibwe Path provides insight into traditional Ojibwe culture, the perils of alcoholism, and a father’s boundless love for his son.

Earl V. Shaffer

Walking with Spring: The First Thru-Hike of the Appalachian Trail

Appalachian Trail Conservancy, 1983

Earl Shaffer’s walk along the Appalachian Trail was a walk with a purpose—Shaffer was traumatized by his service in World War II and wanted to “walk the army out of [his] system.” In Walking with Spring, Shaffer shows his complex inner workings. His sensitive side is seen in the interwoven nature poetry from his trail notebook and his reflections on trauma and war. His rugged and deeply individualistic nature is seen in his impatience to return to trail when he’s in town and his willingness to sleep in broken-down shelters and under fallen trees.

Shaffer’s experiences through-hiking would ring true to anyone who has done a long hike, even to this day: starting out with too many supplies and having to shake down (including cutting the handle off his toothbrush), the confused and variably impressed reactions of townsfolk, and the constant battle between excessive heat and drenching rain. Although the book mostly contains writings about nature and the people he meets, rather than reflections on walking itself, the meditative tone of the book and his gentle nickname for the hike—“The Long Cruise”—show his appreciation for the slow rhythms of walking.

It is worth mentioning that Shaffer also uses this memoir to share his thoughts on politics and local history, occasionally using old-fashioned language to describe Indigenous peoples. Language aside, he is generally respectful toward Indigenous names for places and what would now be recognized as Traditional Ecological Knowledge.

Ursula K. Le Guin

The Left Hand of Darkness

Penguin, 1969

The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula K. Le Guin, is not, strictly speaking, a book about walking, but it does feature one of the most memorable long walks in fiction. Few readers will forget the palpable cold and darkness of the trek over the ice that makes up the second half of the novel—to banish the resulting chill demands long hours soaking in sunlight or dozing by the fire. A classic sci-fi novel set on an alien planet with only one gender, The Left Hand of Darkness follows visiting human ambassador, Genthly Ai, as he struggles to navigate the politics and customs of a strange and markedly different people, a journey mirrored by his walk for survival. Ultimately, his understanding can only come with the mixed solitude and intimacy that walking provides.

Continued Reading: Short Works

How to Walk

by Thich Nhat Hanh

This collection of poetry and walking meditation exercises provides readers with a practical basis for performing walking meditation in their daily lives.

“The Adulterous Woman”

by Albert Camus

Janine, an unsatisfied wife of a disrespectful salesman, watches distant nomads traversing the desert and eventually finds spiritual awakening through a middle-of-the-night walk.

“Kew Gardens”

by Virginia Woolf

In this classic short story, Woolf contrasts the orderly life of a snail weighing his options as he traverses garden plants to the simplistic and gossipy nature of Victorian society.

Lunch Poems

by Frank O’Hara

Frank O’Hara’s urban exploration of Manhattan is sometimes a meandering stroll for a sandwich and sometimes a purposeful march to ruminate on love or grief. Either way, his thoughts on walking and lunching are always delightful to read and often thoughtful enough to provoke contemplation.

“The Man of the Crowd”

by Edgar Allan Poe

An overly observant narrator follows a suspicious figure through the crowded streets of industrialized London, undertaking a bizarre journey as he walks himself into a tizzy.

University of Oklahoma