Writing with a Humble Pen: A Conversation with Tayari Jones

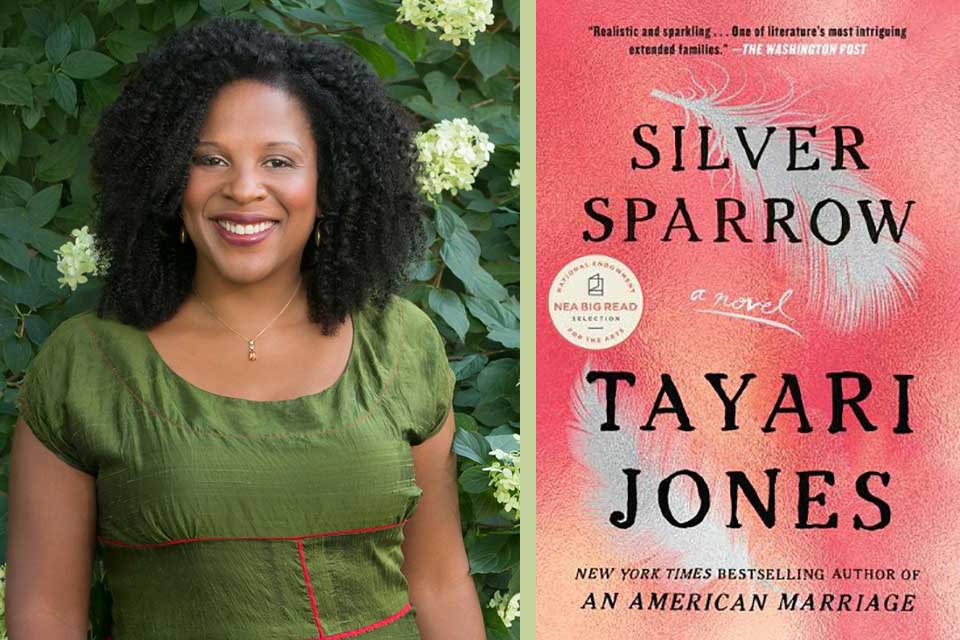

Tayari Jones is a New York Times best-selling author from Atlanta, Georgia. Her most recent novel, An American Marriage, won the 2019 Women’s Prize for Fiction. Jones has been awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award in Fine Arts from the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for Debut Fiction, and was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame. Jones will appear in the eighth annual Aké Arts & Book Festival (October 22–25), an annual literary, cultural, and arts festival in Nigeria that is a space for celebrating creativity on the African continent, which starts today and is free to access digitally. You can reserve your free ticket to attend a book chat on October 23 about her 2011 novel, Silver Sparrow.

Avery Holmes: So, this year’s Aké Festival starts today! What role will you be playing in the festival, and what will you talk about?

Tayari Jones: So I was interviewed by Zukiswa Wanner. And we talked about my novel Silver Sparrow, and just what it means to be writers in the African diaspora, you know, what are the things we have in common? Where do we see the role of literature today? And we also had a great time.

Holmes: Is there anything in the lineup to come that you’re particularly excited about?

Jones: I’m really excited to hear about Victor Ehikhamenor. He’s a writer and a painter . . . (phone dings). I’m sorry, my mother is in her eighties. And she has learned how to send text messages. It is an ongoing problem in my life (laughs).

All right, about that. Yeah, I am really, really interested in the work of Ehikhamenor. Because he is both a writer and a painter, and I’m a great collector of his paintings. So I’m very interested in hearing him talk about the intersection of writing and visual art. Also, I have three of his pieces in my house. Years and years ago, I was photographed by him. I mean, I’m so interested in writers who can do different forms. I feel like they’re maximizing their creative potential. I, on the other hand, basically do one thing, so I’m just so in awe of people who can do so many things.

Holmes: Yeah, that is really amazing. And I wonder how much his work kind of intersects with itself?

Jones: Yes.

Holmes: So, as you know, this past summer, one of the largest racial and justice protests took place, sparked by the murder of George Floyd. I wanted to ask what influence do you think these events might have had on the lineup for this year’s festival?

Jones: Well, I think everyone in the world is focused on the question of justice. I feel like the murder of George Floyd kind of heightened a national (in the US) and an international feeling about the idea of police violence and violence against black people. But I think that everyone who’s participating in the festival was already very well aware of this. And if you think about it, we’re all talking about our books. And our books have been . . . you know, my book came out two years ago, and it’s a book about a young couple separated by wrongful imprisonment. And I started writing the book almost ten years ago now.

So, I think that people have become energized and galvanized, but I don’t think they have been newly exposed or newly made to be concerned or care. I think that now the platforms are more available for everyone to talk about these issues. As before, we used to kind of have to fight and claw our way to bring these things up or, you know, disguise our activism in some other form or this or that, but I think now there’s a lot more room for people all over the world that has been very exciting.

People have been angry about the death of George Floyd specifically, but also looking at the death of George Floyd symbolically, Breonna Taylor symbolically, because people all over the world are suffering from state oppression, police oppression, and for some reason, these crimes against African Americans have become like a malleable and fungible shorthand that people can use all over the world. I don’t know what it is about certain struggles that become this thing that everyone can claim as their own.

People all over the world are suffering from state oppression, police oppression, and for some reason, these crimes against African Americans have become like a malleable and fungible shorthand that people can use.

Holmes: And it’s interesting, which specific people happen to get picked up by the media.

Jones: But it’s a lot of factors aligning at once. I think every atrocity becomes cumulative, like a snowball. So it seems like it is George Floyd, but it really is George Floyd and all the others together. Like, I think if George Floyd had happened with no Trayvon Martin, no Tamir Rice, with no . . . all these, I don’t know if it would have had this galvanizing effect around the world.

The video was just so horrifying. That also was something. And there was no gray area in this one, too. There really was no argument for people who are deniers of the impact of police violence to have. I think it’s just a lot of factors. Sometimes people can get in this spiral of trying to decide why this victim and not that victim, and the fact that this victim got so much attention is a slight to this other victim. I think that all of it goes together. And that’s why I say George Floyd is symbolic of all the others. I think it’s like a synecdoche: the one part represents the whole.

Holmes: Speaking of your mother [Barbara Ann Posey Jones], earlier, she was a US civil rights activist in the 1950s and ’60s, right? Do you think she would have any advice for youth protesters today protesting against injustice?

Jones: I don’t know what advice my mother would have, you know. It was such a different world when she was an activist in the 1950s. You know, they did the sit-in movements at a lunch counter, and so much of the strategy was to be dressed in your best clothes, to look as wholesome and American as possible so that people could see you on TV as an American being treated so terribly. And the strategy is so different now.

But I think that she would advise them to be unafraid, because I think we look back on those young activists in the 1960s dressed in their Sunday best, you know, with their beautiful dresses and shoes. And we forget how incredibly transgressive that was at the moment. You know, I think they’re often derided by people saying, “Oh, they were practicing respectability.” But, you know, they sat down, and it was illegal, and they faced violence. So I don’t think it’s fair to judge them by today’s standards, because today it is not a crime to sit at a lunch counter. So how are you going to look at kids sitting at a lunch counter and critique their clothing, you know, and critique their strategy in a kind of sneering way?

So I think that the key for people now is to really admire the sacrifices of those who came before us. Every time I see someone with a t-shirt on that says, “I am not my ancestors,” suggesting that they are truly activists and are intolerant of oppression, it drives me crazy. I mean, you should be so lucky to be your ancestors. You are your ancestors, you are able to be where you are because of what they did. If my mother and her sister and others in Oklahoma City had not put on their Sunday best and sat down, other people wouldn’t be in a position to wear t-shirts and jeans and be heard.

You should be so lucky to be your ancestors. You are your ancestors, you are able to be where you are because of what they did.

Holmes: And at the time, sitting at a lunch counter must have been terrifying on its own.

Jones: Fifteen years old. That is amazing.

Holmes: That is amazing. My next question is kind of a tonal shift, but are you reading anything interesting right now?

Jones: I am, actually. I’ve just gotten done reading If I Had Two Wings, which is a short-story collection by Randall Kenan. It’s a beautiful collection of stories. And you may not know this, but Randall published his book at the beginning of August, and he died at the end of August. And it’s such a wonderful novel about life in a small town in North Carolina. It’s a fictional town, but he is such an eccentric writer. He was such a sharp social critic but also just a gorgeous storyteller.

Holmes: And the book was published the same month he passed away?

Jones: Yes, he passed away, suddenly. I felt that this book was going to be his moment. But you know, Randall was not the kind of person to live for a moment. After his death, the book was nominated for a National Book Award, but Randall was the kind of writer who carried himself as though he didn’t even know National Book Awards existed. That just wasn’t his thing. He was a writer’s writer.

Holmes: I’ll have to read that. I’m so glad he was able to get it published.

Jones: Yes, absolutely. I’m glad he got to see it.

I do believe that literature changes people’s lives, changes people’s minds, and can change the world. But it takes so long.

Holmes: So, my last question is, do you have any projects in the works?

Jones: You know, I’ve been writing a lot of nonfiction lately. This moment we’ve been in with the racial unrest, and the pandemic, and everything else, has really had me struggling with writing fiction. I do believe that literature changes people’s lives, changes people’s minds, and can change the world. But it takes so long. Literature is a very slow way to change things. You know, it takes me years to write a book, a couple of years for it to get out, then it has to catch on. And sometimes it can take years for the message of the work to permeate, and things feel so utterly urgent now.

But, you know, the thing that kind of freed me up to write was that I started giving money to the funds that pay bail for the young people who’ve been arrested in the protests. Because, you know, I’m thinking, Okay, I’m up here trying to write a story. Yet the story, right now, [is that] people are in the streets, people are dying, people are losing their jobs, and nobody can eat my story. And I realized the luxury it was for me to be like, “My contribution is my words.” And while my contribution is my words, and I do believe in that, I think that it’s not enough.

And so when I started sending money to help get young people released from jail for demonstrating, then it was almost as though my creativity came back to me, because I think one writes best when one writes with a humble pen. And I think that, in giving the money to help do this immediate work, I could go back to the humble work of writing because it’s slow, it’s a contribution, but it’s a slow contribution. And I don’t write well when I’m saying (raising her voice and mockingly banging on her laptop keyboard for emphasis), “This is important. I’m trying to change the world.” I don’t know. The stories couldn’t come to me because I knew that the stories, while important, weren’t the only thing. And then once I gave and helped out with the larger causes—I won’t say one is larger than the other, but more immediate causes—then I was able to do my work. Which is my contribution, but it is a humble contribution.

I think one writes best when one writes with a humble pen.

Holmes: Thank you so much for doing what you do. I definitely agree. It takes a long time, and a lot of work, to actually change a person’s heart. But I want to thank you for all the work that you do.

Jones: Well, thank you. I’ll tell you something funny about when I was contributing this money. Sometimes you need a little levity. I contributed to a bail fund that was called FTP. I thought it stood for “Free the People.” Do you know what it stands for?

Holmes: (laughing) Yeah.

Jones: Yes. Because you’re younger than me. I was like, Oh, isn’t that sweet? So I think if I ever get audited, they’ll say, “What are these checks?” FTP. Yes. I thought it’s for Free the People. So there you go.

Holmes: That’s hilarious.

Jones: I guess it’s the same thing.

Holmes: Yeah, it really is when you think about it.

Jones: Yes, but (she laughs) I blushed.

Holmes: That’s so funny. Well, thank you so much for your time.

Jones: Thank you. The pleasure is mine.