“Singing about the dark times”: A Conversation with David Baker

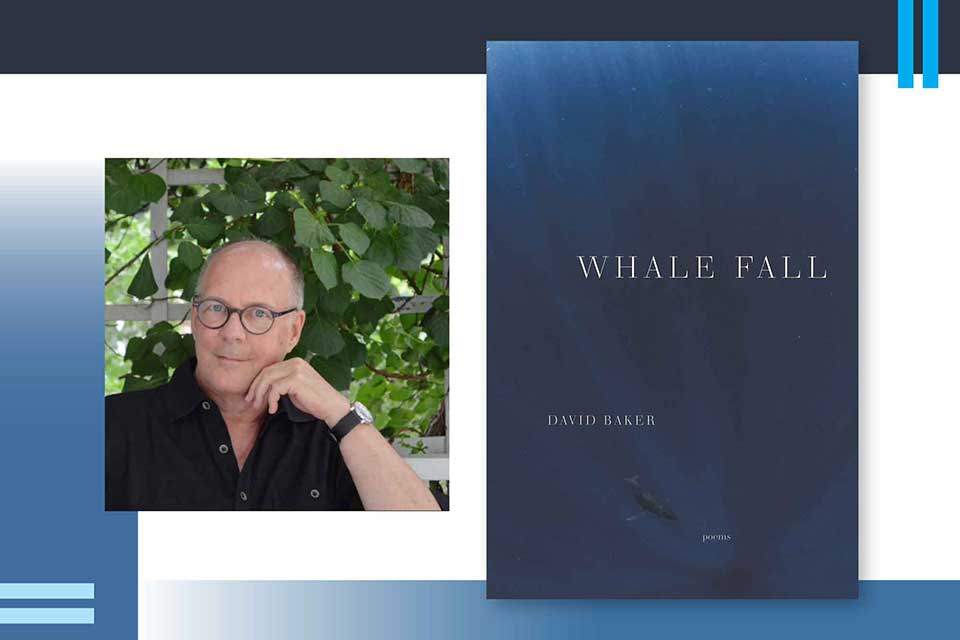

With the 2022 publication of Whale Fall (W.W. Norton), his thirteenth book of poetry, David Baker continues to explore the natural world as both artist and activist. His other collections include Swift: New and Selected Poems (2019), Scavenger Loop (2015), and Never-Ending Birds (2009), which was awarded the Theodore Roethke Memorial Poetry Prize in 2011. Baker recently retired as an English professor from Denison University in Granville, Ohio, where he held the Thomas B. Fordham Chair of Creative Writing. Poetry editor of the Kenyon Review for more than twenty-five years, he initiated in 2015 an annual poetry section entitled “Nature’s Nature” that continues today. Baker’s many honors include fellowships and awards from the Poetry Society of America, the Mellon Foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, and the Guggenheim Foundation. His poetry and essays appear regularly in numerous publications, among them the New Yorker, New York Times, Paris Review, American Poetry Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, and Atlantic Monthly. Don Chiasson, writing in the New Yorker, describes Baker’s influence: “His work evinces the moral courage of keeping still in the landscape; in our era of climate change, poetry’s mandate to measure the rhythms of the year has become a valuable form of witness.” The interview was conducted over Zoom and email during May and June 2022; the following is an abridgment.

Renee Shea: 2021 was a banner year of retirements for you: as a tenured and endowed English professor and as the poetry editor of the Kenyon Review. Might you have staggered them to transition a bit more gradually?

David Baker: The timing just happened this way. Kenyon Review has a new editor who needs a clear space for her own staff, and it’s really nice that I will be able to stay on and curate the Nature’s Nature feature for a while, a project that’s very dear to me. I’m glad not to be responsible [as poetry editor] for reading 20,000–25,000 poems a year! At Denison it was also time to step away. I’m ready to write more, travel more, but in both cases I did not want to completely quit. I can’t stop teaching. Denison offered me this chance to teach two classes every spring, anything I want, and then I’m off for eight months. So it’s the best of both worlds in both cases. I’ve retired . . . but not really. It’s a lucky thing to be able to do.

Shea: You’ve been praised as an outstanding teacher, workshop leader, mentor, editor, and writer. If I’m doing a Venn diagram of these, where is the overlap, the common ground?

Baker: Engagement and connection. But it is not quite an overlap. Writing poetry is very solitary. More than any of the other arts, it’s not a group effort. I’ve been a musician and like to play in bands, in groups, but poetry is 95 percent solitary, yet there’s that 5 percent of time when we really need to sit in one another’s presence around a table and talk about the work. That’s true whether it’s a writing workshop or a literature class, even writing criticism, or editing a literary magazine. There’s some part of me who wants to be a good and invested citizen in that world of art and poetry. All of those activities orbit around that desire.

Shea: As I was reading Whale Fall, I returned to your collection Swift: New and Selected Poems to see the evolution of your interest in poetry concerned with the environment—and it’s a solid presence for the last twenty years, perhaps longer. I’m curious about where you “look.” You grew up in Missouri, right? You have a home in Granville, a charming small town. I think you have had a farm here in Ohio. You and your partner, Page Hill Starzinger (to whom Whale Fall is dedicated), travel back and forth between your place in Granville and her apartment in New York City. And you spend time in St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Your literal powers of observation are so keen that what I’m really asking about is how and where you do that observing—or learned to do it.

Baker: Poetry is about paying attention more than anything else. In some ways, it is loving the world so much that you are deeply engaged in that world. I grew up in Missouri. I liked to be knee-deep in a creek in the woods tromping around with my father, who was an outdoors guy. He was a surveyor, and we’re a family of coal miners and farmers. I’ve never lived in a big city except when I was in grad school in Salt Lake City and for a short time in Columbus. When I was married, we had a place of about ten to twelve acres outside of town with a ravine and pastures, a creek, the whole thing, and I took care of that.

Fifteen years ago, I moved into Granville when I figured since I was going to live alone, I should have some people around me. But just this morning, I was out in the woods walking down a creek bed. In St. John we rent a small house right above one of the bays outside a little village, as secluded as can be. I’m landlocked here in Ohio, and something in me really loves the ocean and the rhythms of the tide. There’s a different demeanor to the landscape and a whole different biosphere and geography.

Shea: What has changed, as I read chronologically, is your sense of what writing about nature means. You’ve spoken of “an eco-poetic” awareness that encompasses activism, a political purpose, what you’ve described as “a growing intentionality.” So how do you define the genre, if it is a genre?

Baker: I’ve found myself evolving over forty years of writing poems. In my first books, critics sometimes referred to me as “a nature poet.” To me, that means a poem where the natural setting is the site of the poem, where the story happens, and it typically is driven by description, the local names and specific features of things. I evolved into something more like an environmental poet fifteen or twenty years ago, where nature is not just the site but the deeper circumstance of the poem. Of course, none of this was intentional. But in an environmental poem the work of the poet becomes more to represent and speak on behalf of that natural landscape or environment and to think more self-consciously about the kind of engagement one undertakes in that setting.

In fact, I have found myself, perhaps over the last ten years, becoming something closer to an eco-poet, for whom nature is not just the site or circumstance but the whole subject-field of the poem. The poet becomes an advocate with a more culturally pointed or political purpose. I have turned toward more engagement with the science of it all—the biology, geology, botany–and sometimes the more technical processes of things. For me, the eco-poem is still written out of that old love of the natural but also out of a newer, perhaps drastic, sense of alarm at what’s happening.

All of this is slippery. Perhaps the umbrella term is nature poetry, and environmental poetry and eco-poetry are specific subgenres. This all has to do with an intentional or purposeful speaking on behalf of a deeper intellectual and emotional complicity. It’s the difference between writing a poem that describes a natural scene and writing a poem that engages or antagonizes or specifically names some of the forces that may be threatening or destroying that scene.

I have found myself, perhaps over the last ten years, becoming something closer to an eco-poet, for whom nature is not just the site or circumstance but the whole subject-field of the poem.

Shea: You’ve been exploring these issues for some time in “Nature’s Nature,” which has been a feature of Kenyon Review every spring since 2015. How did it begin? And how did you come up with that absolutely perfect title?

Baker: It’s a cool title. I actually wrote an essay years before with that title. I had been publishing work in Kenyon Review for a while that engaged with the natural. David [Lynn, KR’s previous editor] had for years encouraged me to do small set-aside features: I did one on Romanian poets, another on violence in poetry. But at some point (and this happened in my own writing and editing), I felt it was time to make a more vivid stand. I thought through what this could look like, and I asked him to give me some pages in the 2015 issue. I am still proud of that first one; then David asked, “Going to do it again?” It didn’t take long to see that this should be an ongoing commitment of mine and the magazine.

Shea: The poets you feature include very established ones (e.g., Rita Dove) as well as newer generations. But you have held to your original “rule” to publish only poets who’ve never been in the Nature’s Nature section. Do you continue to find diversity of background as well as approach (lyrical, argumentative, docu-poems, narrative)?

Baker: I wanted—and still want—only people who have not been in the feature before to keep inviting people to think about doing this work. It’s a way of saying that there are a lot of us and different kinds of voices and positions that people are writing out of—and different kinds of poems. In this 2022 issue, it’s a pretty alarmed group of poems, some decidedly elegiac and sorrowful, and yet there are some joyous poems like Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s wonderful “Bodies in the Air.” It’s important to keep those different qualities of the language to keep the art big and our way of thinking about what nature is and sounds like and looks like as big as possible.

Shea: Now, about the new book—another title question: where did Whale Fall come from?

Baker: A whale fall is a very specific oceanographic term that describes three stages of death and decay. If a whale dies, especially in a deep part of the ocean, it goes through three distinct oceanographic areas, and three very different things happen to that body. It can take as long as a year for the carcass to settle to the bottom.

Shea: The poem “Whale Fall” is fireworks and meditation in concert—news reports, descriptions, equations, images, shifts in perspective, there’s brutality alongside tenderness. How did this extraordinary poem begin? How long did it take to write it? When did you know it was finished?

Baker: It’s a rascal! There’s a two-line poem in this book—and a sixteen-pager. I wrote a long poem for my book Scavenger Loop that took me forever, and I kind of reinvented for myself what a long poem can be. It was a poem about my mother’s death, and it was about farming and the death of farm towns in the Midwest, about agribusiness and poison. I learned how to braid the personal and the political and the natural and the familial.

“Whale Fall” took me about two years. I wanted it to be at once confessional and personal—it’s about my illness for twenty-five years as a form of viral contamination. I wanted to write about nature. And I wanted to get out of Ohio. I wanted to see if I could write a poem whose natural environment is global—every single thing connected to every other thing—and the attempt to communicate over long periods of time and space. I wanted this poem to be impure, to include news items, facts and figures. I don’t think you can write nature poems without knowing the details, describing the mathematical processes, and naming the names. And I wanted to look at just one whale falling. Section I and IV are the first and second stages of “Whale Fall,” and the poem descends (although if you reattach the lines, they are all ten-syllable couplets). Then I wanted more lyrical movements that are not in the ocean but take place in Ohio.

I wanted to move back and forth between movement and stillness, the ocean and the land, lyricism and confessionalism, between medical talk, whale talk, aggregate theory talk. Figuring out how to formalize all those things together—I can’t even tell you! But some things fell into place. I knew I wanted these personal sections to be in couplets. I knew I wanted the whale fall to be descendent. The third stage of a whale fall, the final section of the poem, is essentially where the whale lands and spreads laterally and is in more decay. I wanted the syntax and the phrasing to somehow replicate that process of being pulled apart. For me, little or big poem, it’s always about finding the form of the thing. What’s the line going to be, what’s the syntax going to be like, the tone? For this one, I knew there would be this lateral couplet and this descending stanza. I didn’t know there would be so much prose, nor all of this medical stuff.

I wanted to see if I could write a poem whose natural environment is global—every single thing connected to every other thing—and the attempt to communicate over long periods of time and space.

Shea: How, then, did you know that the title of this poem would become the title of the book?

Baker: It’s the central body at the center of the book. “Whale Fall” took me a long time of writing and rewriting, but before that, all sorts of research and gathering notes. It’s a microsystem of the book. It’s bifocal, too—global and very personal, inland and oceanic, tightly formal and splayed, nature and plastics, diseased and recovered—and perhaps the two identities are embodied in the huge whale carcass and the tiny backyard hummingbird. I’ve never written so fully about my illness and being sick as a parent of a small child. Those narratives are harmonic with the whale fall itself. The poem’s full of formal adventures, from rhymed and syllabic couplets to documentary prose and long-lined free verse to fractal quantitative syllabic stanzas.

None of this was clear at first. All I knew was I wanted to write about the slow descent, decay, and rehabilitation of one dead whale; and about illness, fatherhood, and connectedness: my own backyard as ocean; my memories of medical confusion; my language (anyone’s language) as a zillion bits and pieces in a loose constellation around the text of the self.

Shea: You’ve alluded in this work to your own health situation. In “Snow Falling,” you write: “I had not been well for so long” and “I’m not well, no, not just now” (a poem I read as you reflecting on a time with your young daughter). And the title poem certainly offers glimpses into a struggle with illness. Would you mind talking about your health and medical issues?

Baker: The thing I was finally diagnosed with has a few different names: chronic Epstein Barr disease, myalgic encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue/immune deficiency syndrome. It is a series of viral contaminations. Some people die of it; some just never get better. We didn’t know what was wrong with me when I first got sick in 1993 and for nearly a year afterward. I was tested for everything. I remember my young doctor coming back after more blood tests and saying, “We figured it out. You’ve got mono.” I said, no, I’ve already had mono and you can’t get it again. But it turns out that you can get it again, or a mutated, awful version of it . . . like a T-Rex mono. It’s devastating, brutal, and has a cascade effect that allows other latent viruses to emerge. Over the course of the next two years, everything went wrong with various of my organs and systems—spreading from one weak system to another. I was sick for about four or five years.

At last I decided to try everything possible to get better: vitamins, analysis, hypnosis and self-hypnosis, meditation, radical change of diet, lowering some expectations, mindful acceptance . . . and I finally got better enough to think I was going to be okay. But then it would come back in relapses, in slightly less serious bouts. About four or five years ago, I did get sick again with a powerful recurrence. I ended up at Wexner Medical Center with Dr. Julie Mangino, an infectious disease specialist. So I continue to have this chronic illness. To my mind, at least that gave me the experience to write about viruses and about something like environmental health and disease as a kind of contamination—a viral calamity.

Shea: Maybe that explains in some way why as I read through Whale Fall, my vocabulary expanded: mullein, mustard dates, beggar’s blanket, Liquid-Ambar styraciflua—scientific names, Latin names, folksy names that become their own song, litany, or mantra. (In “Sensationalism,” your listing of the names of birds is a poem in and of itself: “avocets, stilts, willets, killdeers/coots, phalaropes, rails, tule wrens, yellow-headed blackbirds, black terns . . .”) How does your inclusion of what must be to most readers unfamiliar and likely unusual vocabulary reflect your ideas about the language that is available to us to talk about our endangered natural world?

Baker: I love the names of things—the old names and the new names. The original definition of the poet is the namer. I’ve gotten more and more comfortable and obsessed by the etymologies, the Latinate terms, as a way to invite everything in—all the different kinds of languages. In a poem like “Whale Fall,” I wanted it to sound like an orchestra rather than a solo piano; I wanted there to be a lot of instruments rising and falling in harmony and discord, moving in and out of different kinds of voicing that an orchestra can provide. I know that some of my readers don’t know some of the words . . . but so what? I try to imagine a reader more qualified, smarter, more well-read than myself—but also with a bigger heart than mine. I try to write to her, thinking even if she doesn’t know this formula or this word, if I write my poem well, she will have a context and will look it up. I love to do that when I read somebody else’s poetry. I don’t read poems to find confirmation for what I already know; I want to be put in the company of strangeness—of otherness and discovery.

Shea: One reviewer wrote that you are “wonderful at smuggling narrative into what look like meditative poems”—and I kept thinking about that odd use of “smuggling.” Yet when I read “Gravel,” it made perfect sense. That poem has such lyrical intensity juxtaposed with straightforward, almost clipped sentences: “I park the car. I pick my step / past rusty barbed wire . . .” The synergy of the two seems to me where memory happens (“Back . . . back . . . back”). Is this you “smuggling”?!

Baker: Every single linguistic event is narrative. The relation of a subject to a predicate is narrative . . . time is passing . . . something is evolving. It may be an instant or years or epochs. It took me a long time to realize that. I used to think that there were lyrical and narrative poets, but that’s a bone-headed distinction. A poem is not a poem if it’s not lyrical: it’s just data. And language is always narrative, but the question is whether the narrative is linear, cyclical, extended, compressed. Moving back down this country road [in “Gravel”], I rediscovered an old house that my father and I had seen forty years earlier. Going from state highways to asphalt to gravel to a tractor road—that “back . . . back . . . back”—became an occasion for memory in going back to an emotional landscape.

Shea: I’ve asked you to read “Middle Devonian” and then talk about it—because it feels to me like a poem that brings together many of the concerns you’ve just described and that animate this collection overall. But before you read, would you explain for those readers who—like me—don’t know what the Middle Devonian period is?

Baker: It’s an epochal period hundreds of millions of years ago. It was a dinosaur period when much of North America was underwater. The term came to me from a geology friend of mine, Bob, when we were walking through a creek bed. He’s a rock guy. So this is one of the geological periods when trilobites and coral and ferns were more among the population than we were. It took place on the farm I used to have. The neighbor is a blend of my friend Bob the geologist, my ex-wife who finds fossils and polishes them, and a neighbor who would show up in our backwoods hunting.

Middle Devonian

You can’t kill it, my

good neighbor

tells me. He means the half

acre of bamboo seeded

from waste run-

off from the

new development—

just beyond the woods, there, beyond

the creek bed. Can’t

dig it out. Can’t blast it out.

And you can’t hack it out with your machete

or a big old chainsaw. No way.

But he’d rather

have the bamboo than all those houses

going up. Who are they?

Why’d they rip out

the beech trees

and bulldoze the pawpaws?

Godawful houses.

And then they planted trees, in rows!—can you

believe that?

We’re walking the

cold creek bed,

looking for fossils, the coral, the hollow

stem-tubes,

from when this

was all a salty shallow sea.

He polishes them for

his grandkids. He

mounts the good ones, labels

them—the brachiopods, the trilobites—

like little jewels, like magic

lifted from the shale-

beds and sandstone

of the creek. He’s got his fingers in

the water again. This one here’s a keeper.

Goldringia cy-

clops, I think. Middle Devonian.

It’s got a cyroconic shell. That means, he says,

the whorls don’t touch. Crenulate frills . . .

it’s a nautiloid, not

an ammonoid.

There’s been an early freeze this

week, a bit of snow, the remnant crust

upthrust and broken,

curling in sunshine

here and there, in the mud.

It’s thin as good dishes.

Here’s one for you.

You know the pawpaw’s

science name? He’s moved into

the rutted pathway, where kids from the houses

smear their loud four-wheelers.

Asimina triloba.

How’s that for irony?

Then we’re quiet for a while—bird song

at the level of

the branches. Old language

in the leaves—late wren?—not in a hurry, but

stirring. So he says, Go Bucks.

What? Oh,

just thinking about the fire

out West. I read they’re burning like eighty

football fields of prairie

every single minute.

What the hell

kind of way is that to measure something?

Beats me—. I guess

it’s how they think

we understand the size.

I can tell he’s ready to leave.

People round here love their trucks and football.

He pats his pocket

full of rocks—keepers for

the kids. Go Bucks, he says again.

Godawful. Think of that. One minute

and it’s four hundred million years.

Shea: It isn’t a difficult poem in the way that “Whale Fall” or “Echolocation” is—but there’s a complexity in the structure, and the dialogue works so well here because the registers keep moving.

Baker: I like to find room for dialogue in poems—a little play within the poem, a little drama, and juxtapose that against the science names and the lyricism of the thing.

Shea: And the Buckeyes . . .

Baker: I’ve been in Ohio for about forty years, and it’s about time I got to say “Buckeyes” in a poem!

Shea: So, some people have to lookup Middle Devonian—and others will have to check out the Buckeyes! And those are certainly different time periods. The way you interlace various shifts is remarkable—the Middle Devonian, suburban sprawl, three generations as Bob collects fossils for his grandkids, the tenacity of bamboo: “One minute / And it’s four hundred million years.”

Baker: In this poem, there are different kinds of stories being told over different kinds of time. Five minutes walking down the creek bed and 400 million years told in the narrative, the text of the creek bed with the language there embedded in the rocks. In between all these are different kinds of narration: jokes, science talk, my friend explaining to me the etymology of this one fossil—all those things working at once.

Shea: One of the hallmarks, if you will, of this collection seems the challenge to the binary of science vs. art (or poetry), the emotional and lyrical vs. the objective and factual. I kept hearing Martin Luther King Jr: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.” The context is different, of course (“Letter from Birmingham Jail”), but it’s the same connection, a reminder that we’re all in this together. Could you talk about how that perspective or reality has become more pronounced in this new collection?

Baker: The term “mutuality”—that’s so interesting because it’s very similar to a term that cultural biologists, mathematicians, environmental scientists, botanists all use: “mutualism.” It’s the same phenomenon that says—I’m kind of channeling Timothy Morton here—what we regard as nature, not this stream or continent or globe but this universe, is a single living entity, and every action in one part of that (what Morton calls hyperobjects) has a potential effect on every other one. To think we are separate or our lives are separate from a tree or a waterfall or a star system is simply a mistake. How do you write about those huge things? How do you not? Sometimes you have to write them through very particular, focused, microscopic attentions, sometime with a kind of sweeping inclusion. That’s why I’m glad I can write more than one poem and can operate in each of these fields at different times.

Shea: “Middle Devonian” and the title poem are examples of such long, complex, rich studies. Yet you have some very brief poems that pack a real punch. I’ve read the five lines of “Extinction” over and over, puzzling over the “you” and “they” and thinking about the opening speculation:

When you are gone they will read your footprints,

if they still read, as they might a poem about love—

wandering in circles, here and there obscured,

washed out in places by weather, sudden landslide.

Keep walking, pilgrim. This is your great tale.

I wonder if in many ways the final heartbreaking line is ultimately, essentially, what you’re asking of your readers.

Baker: That’s the “you” of the poem—whoever that pilgrim is: it is everybody, the poet, some entity that has been long gone and all we see are the fossils, the footsteps. That’s one of those poems that tries to think about long, sweeping passages of time, but I deliberately wanted to think of those in little bitty poems.

There are these ghosts throughout the book of the absent—sometimes they are friends or family, species, sometimes one’s self or one’s younger, aspirational self. But then the book moves into a kind of rediscovery of things—my daughter shows up, Page shows up by name in several poems, so there’s a kind of hopefulness as well.

There are these ghosts throughout the book of the absent—sometimes they are friends or family, species, sometimes one’s self or one’s younger, aspirational self.

Shea: In one of the early Nature’s Nature introductions, you described a “combination of urgency and hope.” You acknowledge that the “devastation and peril often feel so massive they are already beyond words,” and “Ultimately, every one of these poets shares a sense of palpable anxiety”—but are you still hopeful?

Baker: I don’t know. I’m hopeful day by day, I wake up in the morning and am grateful to be an animal in the world breathing the air, drinking the water. I don’t think we have an honorable manner of living on this planet, and we have done damage that won’t be fixed—and we won’t be here all that long compared to the expected life span of most species. I’m not hopeful about that. I don’t see us doing enough to fix the damage. I am hopeful that other species will survive, and the earth will be here—and something beautiful will evolve out of what is here. I don’t know what it will look like. I wish I could be there and see it. But I am skeptical about our own species’ capability to get it together enough to act responsibly and with honor for everybody’s lives.

In the latest edition of Nature’s Nature, I quote this poem by Bertolt Brecht: “In the dark times / Will there also be singing? // Yes, there will be singing. / About the dark times.” That’s exactly the formula—those two things together. It’s why a musician plays an instrument, a dancer dances, a poet writes a poem: it’s a form of ecstatic necessity to make something beautiful.

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!

Editorial note: “Middle Devonian” and “Extinction” from Whale Fall: Poems (2022), copyright © 2022 by David Baker. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.