Intern’s Pick

Andrzej Sapkowski

The Last Wish

Trans. Danusia Stok

Sword of Destiny

Trans. David French

Orbit

“And our destiny. It isn’t a fairy story, it’s real life. Lousy, evil, onerous . . . not sparing anyone, neither witchers, nor queens” (Sword of Destiny). The warrior queen Calanthe of Cintra may insist that the world is not magical but harsh and cold, but the fantastical elements of this world cannot be dismissed, even by a commanding monarch. The Witcher series by Andrzej Sapkowski is filled with monsters and myths; it is ripe with magic and overflows with familiar characters from fairy tales. Despite the heavy presence of fairy tales and magic in this series, there is a balance between the mythical and the mortal, legendary fights tempered with friendship and romance.

Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski wrote his first iteration of The Witcher in 1986, while working for a fantasy magazine as a literary translator. His short story placed third in the magazine’s fiction competition; from that short story he wrote two collections of short stories, The Last Wish and Sword of Destiny, followed by a chronological storyline told over the course of six novels. Sapkowski’s meticulously crafted story and monster-slaying hero have gained an increasingly fervent audience with every rendition. His work has been translated into numerous languages, gaining popularity first in his native Poland and finally reaching the US in 2008, more than twenty years after the original publication. Danusia Stok and David French translated the English versions of The Last Wish and Sword of Destiny, respectively; both translations expertly capture the essence of Sapkowski’s fictional world.

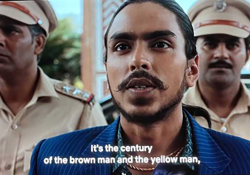

Some of Sapkowski’s short stories aren’t entirely well served by the television adaptation, but the majority are faithfully depicted in the first season.

As the Witcher’s popularity has spanned cultures, it similarly spans media forms, from comic books to video games and movies, and, most recently, the wildly popular Netflix series. The episodic nature of the short stories in The Last Wish and Sword of Destiny effortlessly translates to actual episodes. Some of Sapkowski’s short stories aren’t entirely well served by the television adaptation, but the majority are faithfully depicted in the first season.

The Last Wish introduces Geralt of Rivia, alternatively known as the venerable White Wolf, or the infamous Butcher of Blaviken. In a world of faeries and sorcerers, overrun with monsters both familiar and obscure, ordinary people need protection. Witchers answer this call, often unwillingly. Unfortunate, unwanted children are “turned into monsters to kill other monsters” (The Last Wish).

Selected and trained from a young age, a lucky one in ten will survive the Choice, then the Trial of the Grasses, and finally the Change, a perilous process that replaces human eyes with cat eyes and hearts with, well, nothing, if the rumors are true. As if eager to galvanize these rumors, Geralt murders three slightly bothersome men within the first ten pages of The Last Wish. The story opens with gratuitous violence and does not shy away from the violence that is often necessary, but while Geralt may not adhere to the dictates of men, he clearly abides by an ironclad code.

The Last Wish and Sword of Destiny introduce Geralt’s tale and his world. In these episodic, nonchronological tales spanning decades, we piece together Geralt’s tumultuous timeline and begin to see a faint outline of his future with Princess Cirilla of Cintra. His days are stuffed with misadventure. In “The Witcher,” he transforms a striga back into a princess; in “The Lesser Evil,” he gains his begrudged moniker: Butcher of Blaviken. In “The Edge of the World,” he is captured and threatened by the elves of Dol Blathanna near the edge of the conquered world, then spared by their queen, Dana Meadbh, Queen of the Fields. “A Question of Price” finds him saving a cursed man from a cold, haughty queen who refuses to uphold “the artifice of decorum and fairness” that her court requires (Netflix, episode 4).

As the short stories jump between past and present, with quests ranging from deadly to absurd, the reader is thumped with Geralt’s moral code, unwavering whether he is translating a spat between a duke and his mermaid lover or rescuing a lost princess from Brokilon, the ancient, sinister forest of the elves. In between his questing and killing, Geralt falls in love—if a witcher can do such a thing. Geralt is enamored with the ravishing sorceress, Yennefer of Vengerberg, who is “beauty and menace” married together. Their overwrought love story is doomed by their cold hearts, which seem pierced by Aedd Gynvael—a shard of ice.

This world of monsters and mayhem would be replete without a love story, but Sapkowski concocts a few.

This world of monsters and mayhem would be replete without a love story, but Sapkowski concocts a few: the convoluted love of a witcher and his sorceress, both monsters in their own right; the reluctant love of a hero and his loyal, renowned bard; and the surprising love between an unattached, infertile man and his unwanted, unclaimed Child of Surprise, a child promised to him by destiny. The elements of the mythical and the human—or witcher—combine to create a fantasy world ripe with commanding characters.

Season 1 of The Witcher was released in December 2019; the success of the Netflix adaptation has meant new interest in Sapkowski’s books. It simplifies superfluous complexities but retains the disjointed, diachronic timeline that Sapkowski introduced in the short stories. Many of the episodes closely mimic the short stories. “The End’s Beginning,” episode 1 of The Witcher, adapts the short story titled “The Lesser Evil.” The episode is undisputedly a simplified version of the short story, but many lines of dialogue are lifted directly from the short story: “You have not changed a bit, Stregobor. . . . You’re talking nonsense while making wise and meaningful faces.”

Lines like these evince the same charmingly direct witcher that Sapkowski created. Unfortunately, in the Netflix series there are times when the dialogue sounds unnatural, forced in when it clearly does not fit the modified storyline. Other than a few occasions only noticeable after reading the short stories, the Netflix adaptation thoughtfully translates a complex narrative with a rich, complicated story world, keeping the details necessary to retain the story’s richness and eliminating elements that would overwhelm an eight-episode season.

University of Oklahoma