Motherhood, Grief, and a Call to Action in Anna Starobinets’s Look at Him

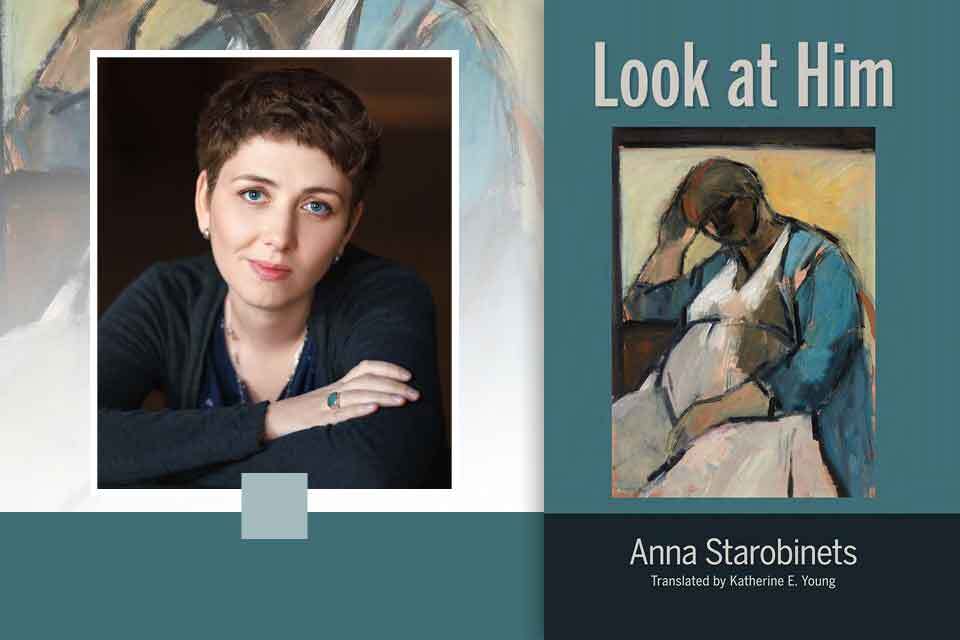

Written by one of Russia’s best-known horror writers, Anna Starobinets, Look at Him (Three String Books, 2020) is an unusual book: it reads partly as a memoir and partly as a journalistic investigation. As translated by Katherine E. Young, it will interest scholars who work on the medical humanities and anyone concerned with issues of motherhood, reproductive justice, and medical ethics.

The first two-thirds of the volume offers readers a first-person account of a pregnancy that ends in a devastating loss. Informed, during a routine ultrasound performed at sixteen weeks, that her unborn son suffers from a profound birth defect that will inevitably lead to death immediately after birth, Starobinets faces hard choices and has to navigate a Russian health system that offers parents in such situations few choices and little psychological support. Told that her only option in Russia for what is deemed a late-term abortion is a state hospital that offers punitive conditions (no anesthetics; forced dilation and curettage; horrifying abortion methods), Starobinets opts to travel to Germany with her husband, where she finds much more sympathetic medical personnel who recognize the importance of helping families to heal and mourn from such devastating losses. Although at first she plans not to see her aborted baby—she is worried he will horrify her and haunt her dreams—ultimately, with the encouragement of German medical personnel, she takes the time to “look at him” and finds it healing. Nonetheless, after she returns to Russia, Starobinets has “sorrowful, anxious dreams” featuring her son, always allusive, with his face turned away and hidden (61–62).

Starobinets provides an affecting portrait of family relations amidst great tragedy.

In Look at Him, Starobinets provides an affecting portrait of family relations amidst great tragedy. The book details the reaction of her eight-year-old daughter to the bad news about the pregnancy, Starobinets’s own debilitating depression both before and after her abortion, and her husband’s efforts to be present and supportive (though he is a secondary presence in the narrative). Grief seeps into the family members’ dreams and play sessions. In a particularly affecting scene, the daughter, in play therapy with a child psychologist—the one Russian medical professional in the book who leaves a positive impression—translates the family’s loss into a fairy tale about a witch who plans to poison a special baby with an apple (73–75).

The last third of Look at Him is journalistic and contains interviews with other Russian women who suffered similar losses and also with German midwives and doctors who assist with such difficult pregnancies. Starobinets notes in the introduction to this journalistic section that she had hoped to also interview Russian medical specialists but found, despite overtures to multiple hospitals and clinics, that no one was willing to speak with her. “I might,” she notes, “have been able to get to them through the ‘back door,’ . . . but I chose not to. It seems to me that the situation I’ve described reflects reality best of all, and that it so graphically demonstrates the difference in approaches that nothing more is needed. On the one hand, we have the German system, plainly oriented to the individual. . . . And on the other hand, we have the Russian system—closed off to the individual under lock and key” (95–96).

Starobinets’s account of maternal health care in post-Soviet Russia sadly recalls the distressing descriptions of the state of Stalin-era and late-Soviet obstetrical and gynecological care from Ludmila Ulitskaya’s The Kukotsky Enigma.

Starobinets’s account of maternal health care in post-Soviet Russia sadly recalls the distressing descriptions of the state of Stalin-era and late-Soviet obstetrical and gynecological care from Ludmila Ulitskaya’s 2001 The Kukotsky Enigma (published in English by Northwestern University Press in 2016). Look at Him offers readers both an affecting portrait of parental grief and a call for action to address these long-standing systemic problems and improve women’s health care in Russia. The translation by Katherine E. Young is excellent. Look at Him was a finalist for the 2018 National Bestseller Prize in Russia.

University of Oklahoma